Below is a transcript of my talk at the Process Philosophy, Plasma Cosmology, and Transpersonal Psychology meeting in Exeter, UK, which took place July 24-27, 2025. Other attendees include Robert Temple, Timothy E. Eastman, Barnard Carr, Steve Odin, Andrew M. Davis, Nick Cook, Ashton Arnoldy, John Priestland, Massimo Teodorani (virtual), Jeffery Kripal (virtual), Kelly Chase, Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes, Dana Kippel, and Jude Currivan.

So I’m going to talk a little bit about the connections I see between plasma cosmology and the philosophy of organism of Alfred North Whitehead. He also referred to his work as “organic realism.” As we’ll see, there are many connections between this more organic understanding of the universe—where, as Whitehead put it, physics is the study of the smaller organisms, particle physics the study of the smallest, astrophysics the study of the largest, and biology the study of the middle-sized organisms here on Earth. So, for Whitehead, “organism” becomes a kind of master metaphor.

The discovery of plasma dynamics and the self-organizing tendencies of plasmas lends itself, I think, more to an organic metaphor than a mechanistic one. I’ve started here on my title slide with a few quotes from who we might call the first process philosopher, the ancient Greek presocratic physiologos, or natural philosopher, Heraclitus. He said that all things are fire—an “ever-living fire.” I’ve translated another of his fragments as “lightning lures all entities toward order.” It’s usually rendered, “the thunderbolt steers all things,” but I’ve translated it in a more Whiteheadian way.

On the other side here: “The cosmos, the same for all, neither any god nor human has made, but it always was, is, and ever will be: an ever-living fire, kindling and extinguishing in measured rhythms.” Already, there is the hint of a challenge to the creatio ex nihilo Big Bang theory—which is, I think, a little too theological in the wrong sense. I have nothing against theology, but I think we should do our theology more consciously.

Plasma is often referred to as the fourth state of matter, with solid, liquid, and gas as the first three. (Solid as “the first” seems to be given priority for some reason—which to me suggests that our physics is still a little too geocentric, despite post-Copernican pretenses of having gone beyond an Earth-centric view.) Rather than thinking of plasma as this anomalous afterthought, perhaps we should think of it more as the prima materia out of which solid, liquid, and gas precipitate.

If we go back to the hottest, earliest stages of the universe—and I am fully on board with an evolutionary, time-developmental picture, even if I will challenge the Big Bang model as we move along—this quark-gluon sea in the first microseconds of cosmic life is a plasma. And then at the largest scale, in these galactic superclusters, we can see Birkeland currents binding them together. At the solar system level, as we’ve heard, plasma composes 99% of the visible universe, of normal matter, even though in the Lambda-CDM model, 95% of the universe is this invisible dark stuff that nobody knows anything about.

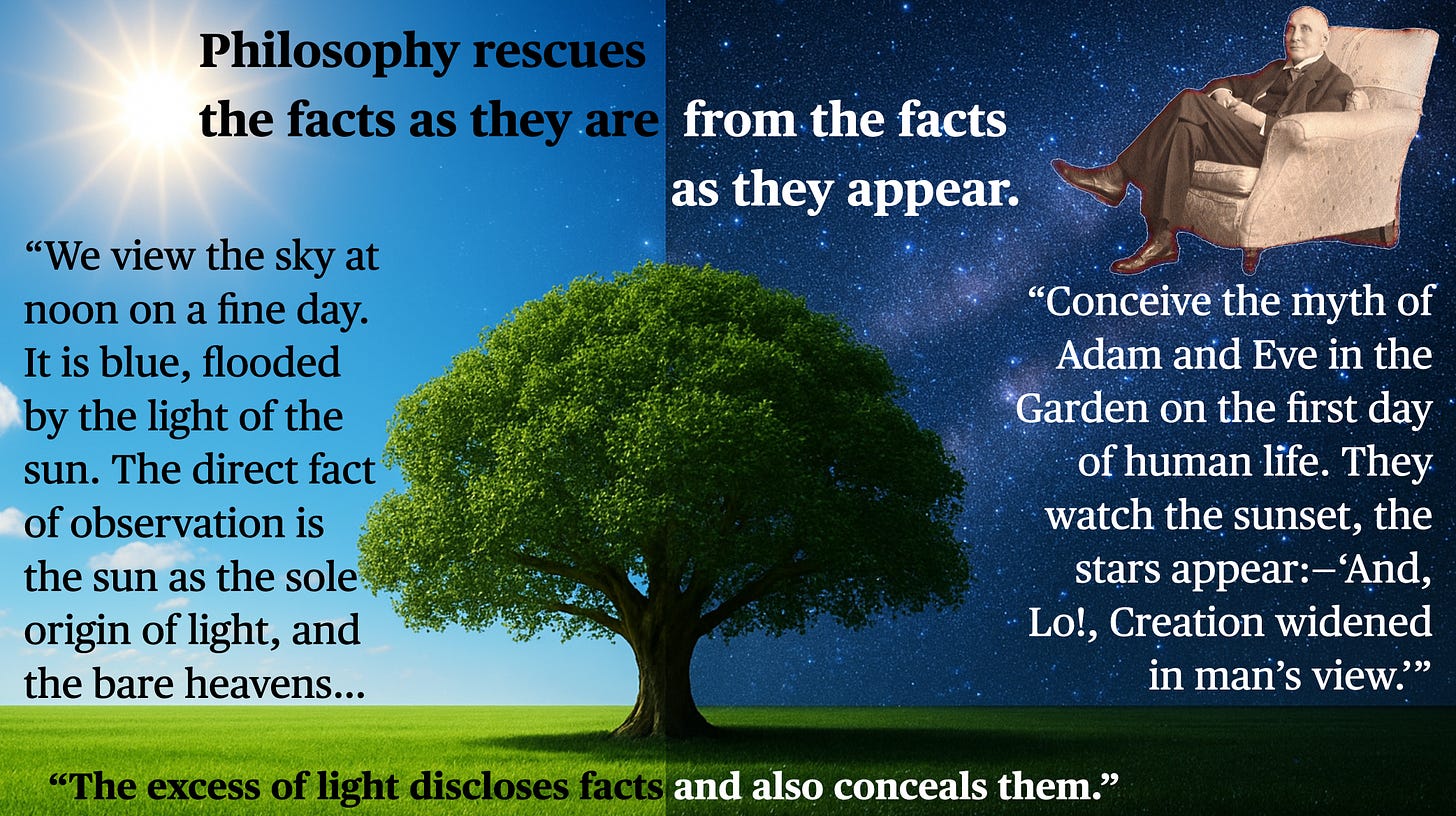

Let me start with a quote from Alfred North Whitehead’s Adventures of Ideas that gives us a sense of the relationship between the visible world we see with our everyday senses, and the invisible world represented—at least in part—by electromagnetism. We can certainly detect electromagnetism, but we don’t see most of the spectrum with our eyes. Whitehead says:

“Philosophy’s task is to rescue the facts as they are from the facts as they appear. We view the sky at noon on a fine day. It is blue, flooded by the light of the sun. The direct fact of observation is the sun as the sole origin of light and the bare heavens. Conceive the myth of Adam and Eve in the garden on the first day of human life. They watch the sunset, the stars appear, ‘And lo, creation widened in man’s view.’” (He is quoting Joseph Blanco White.)

The point here is that the excess of light discloses facts, but also conceals them. Electric currents may be invisible to our physical senses—except when they give off light and warmth that we can detect. Yet electricity, electromagnetism, is detectable with subtle instrumentation. The takeaway lesson from Whitehead here is that we shouldn’t limit our vision of the cosmos to what the physical senses reveal—even as we take care not to allow abstractions to replace concrete realities.

Let’s think about the sun for a moment. The sun above our heads is, at first glance, the most obvious feature of our everyday human existence. It reliably greets us every morning, departs every evening, and reveals innumerable other suns—whole worlds—beyond our own. Our lives and deaths unfold beneath its generous light. We see and eat only by grace of its radiant warmth and energy, and we sleep in the shadow of its retreat.

But what is the sun? Opinions differ. Many mysteries remain, even for modern heliophysics. So deep is its logos, as Heraclitus might say.

If we go back to ancient Greece, for Homer, the sun was Helios—a god whose daily chariot ride across the heavens marked the rhythms of mortal life. Heraclitus saw the sun as the epitome of the perpetual novelty of the universe; he declared it “new every day.” Anaxagoras, an early materialist, saw the sun not as a dying and rising god, but as a glowing stone—a globule of molten rock flung up from the Earth’s surface, ignited by the swift currents of the ethereal vortex in the heavens.

Contemporary astrophysicists have established that the sun is composed almost entirely of plasma—a high-temperature, electrically conductive sphere, classified as a G-type main-sequence star. It’s often described as a sphere of ionized gas, but, as we’ve heard, that is a wholly inadequate account of what plasma really is.

Stars are typically understood as balls of ionized gas, held in a temporary balance midway between nuclear fusion at the core, which pushes outward, and gravity’s relentless inward pull. Plasma cosmologists are not satisfied with this “gravity-only” and “nuclear fusion-only” picture as the sole cause of star formation. Instead, they envision that the universe produces stars as a result of immense Z-pinch plasmoids forming at the nodes of vast galactic electric currents. Electromagnetic forces, in this picture, pinch and sustain the swirling mass of plasma around the surface of the sun, which would be considered hollow, rather than generated by internal nuclear processes at the core.

Rather than being held in neutralized gravitational equilibrium, stars are actively sculpted by these dynamic magnetic fields. The sun’s influence extends far beyond its visible light and warmth.

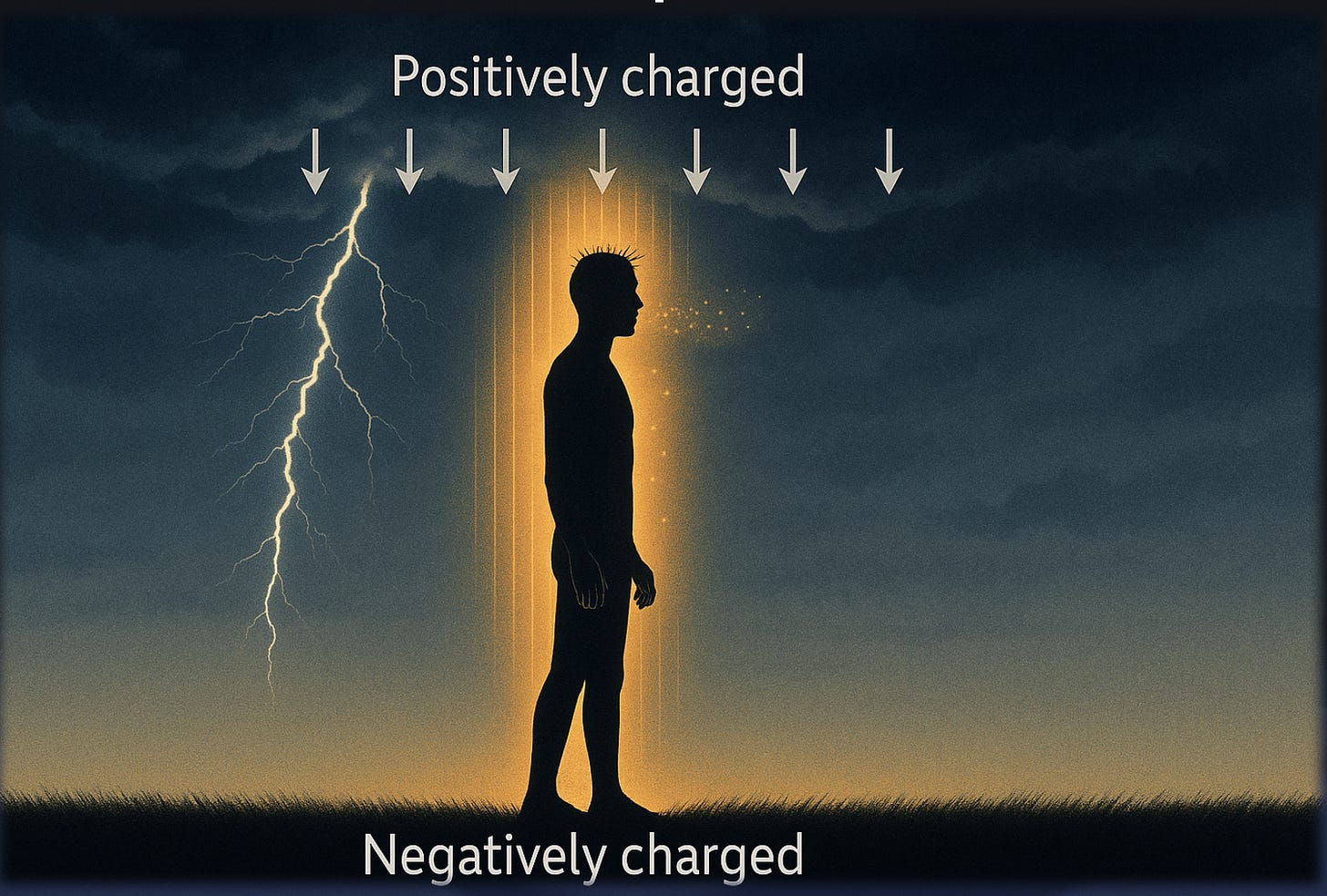

Every dawn—something I just learned a few days ago from Rupert Sheldrake, on a bit of a pilgrimage with him in Sussex—when the sun rises, it initiates an electrical transformation of the planetary environment. As the first rays of sunlight touch the upper atmosphere, they ionize it, dramatically altering the electrical relationship between Earth and sky. The atmosphere normally maintains a potential difference of about 250,000 volts, relative to the Earth’s surface. As the sun rises, it undergoes a diurnal breathing—a daily electrical respiration tied to the sun’s presence.

This planetary and solar electric circuit has a current density that doubles or triples as sunlight sweeps across the surface, with thunderstorms worldwide contributing to this planetary electrical heartbeat pulsing in rhythm with the sun’s diurnal cycle. We ourselves—our ensouled bodies—are immersed in this electrical environment, though we may not consciously perceive it. When we stand upright on a clear day, our heads exist at an electrical potential approximately 200 volts higher than our feet. This voltage gradient is comparable to household current, though we don’t feel it because there’s no significant current flowing through our highly resistive bodies. Nonetheless, we are like living electrical dipoles, biological antennae extending into Earth’s atmospheric circuit.

Our upright posture, so often thought to distinguish our species from other animals, places us in a unique electromagnetic relationship with the planet and the sun. This vertical stance maximizes our exposure to the atmospheric voltage gradient and makes us, in effect, biological batteries—plugged in between the negatively charged Earth and the positively charged upper atmosphere. Every step we take slightly disturbs this field; every breath we exhale releases ions that modify the local electrical environment.

Some researchers suggest that this ambient electrical field influences our biological rhythms, cellular ion transport, and neural activity—we, and all other organisms, are involved within this electrical matrix, our physiology shaped by millions of years of exposure to these atmospheric currents. In this sense, we are not just passive occupants in this electrical environment, but active participants in a bioelectrical exchange that extends through the whole solar system, the galaxy, and even between galaxies.

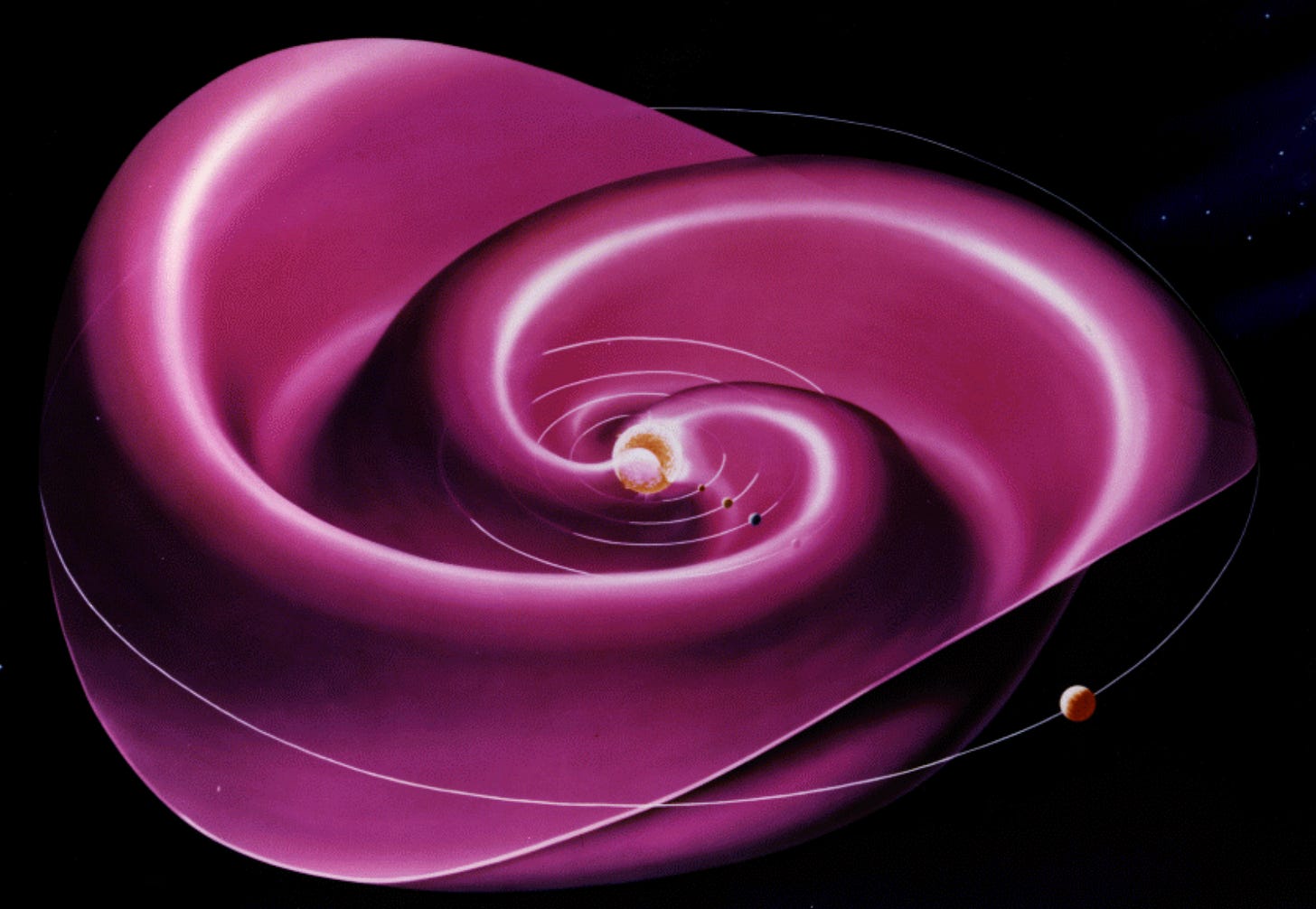

This is a NASA-commissioned artwork by Werner Heil depicting the plasma sheets that extend out from the sun as it rotates. To me, it looks almost like a rose. Rather than thinking of the sun as a simply located ball of burning gas, it is more like the living heart of a spiraling plasma rose, extending twice as far as Pluto’s orbit. At the edge of our solar system, it piles up and bursts, evaporating into the interstellar cosmic environment. We exist on Earth in the midst of this blossoming nexus of what Whitehead would call electromagnetic occasions of experience.

Let me turn now to a few thinkers in addition to Whitehead: Irving Langmuir and Kristian Birkeland. Langmuir coined the term “plasma” in 1928, trying to distinguish it from mere ionized gas, and he wanted to evoke its organismic qualities. Plasma for him was connected to the life-bearing fluid of our blood; the plasma currents flowing through the solar system and the galaxy were akin to the circulation of our blood. Plasma, rather than being a passive background, is more like a responsive field that exhibits behaviors more akin to living tissue than to dead particles.

As I said earlier, plasma physics really does cry out for organic metaphors to understand it. Electromagnetic forces coursing through plasmas choreograph collective emergent patterns—spiraling filaments, double-layered toroidal spheres. These forms prefigure the morphogenetic potency of life, of biological organisms as we know them. So, in 1928, Langmuir was coining the term “plasma” as he studied these effects in his laboratory—at the same time Whitehead was developing his ideas about the “electromagnetic society” that dominates the cosmic epoch we inhabit, in Process and Reality, which he wrote in 1928 and delivered as the Gifford Lectures in Edinburgh.

Birkeland, meanwhile, was working on theories of the aurora borealis, trying to understand how currents from the sun could produce those effects here on Earth. He was ridiculed at the time, but wrote in 1908: “It does not seem unreasonable to think that the greater part of the material mass in the universe is found not in the solar system or in the nebulae, but in empty—so-called empty—space.” As we’ll see, Whitehead doesn’t think there is such a thing as empty space, because it is pervaded by plasma.

Here is an AI depiction of the electrical currents around the sun. I would say modern plasma physics has made good on Heraclitus’s speculative claim that the cosmos is an “ever-living fire”—or, as we might say, an ever-living plasma. We shouldn’t relegate it to the “fourth state of matter”; I really do think we can elevate it to a kind of prima materia. Whitehead helps us here when, in Process and Reality, he refers to our cosmic epoch as a “society of electromagnetic occasions.” So, rather than thinking of the universe as being dominated solely by gravity, we should recognize that gravity works in concert with these electromagnetic effects.

As I said earlier, the gravity-centric focus of astrophysics remains too geocentric, and we might refer to the force of “levity” that plasma represents. The universe isn’t just solid bodies colliding in empty space; as Whitehead and Birkeland indicate, there really is no such thing as empty space. Plasma is pervasive; its levity lifts all things toward life.

Here’s one of Birkeland’s famous experiments, the so-called Terrella, or “little Earth,” experiments, first conducted in 1913. There is video of him shooting electrons at a magnetized sphere—the “little Earth”—creating an aurora effect. He did this work at the University of Oslo and made expeditions to the Arctic to observe the aurora. He was trying to demonstrate that electromagnetic forces can create the patterns he was seeing in the sky at the North Pole. He was ridiculed for this; the idea that electric currents could flow between the sun and Earth along magnetic field lines was simply not something physicists were ready to accept. Lord Kelvin dismissed his ideas as nonsense. Sidney Chapman, a leading geophysicist, developed an alternative model that rejected the possibility of currents traveling through space.

Birkeland died in 1917, his ideas relegated to the footnotes as the fantasies of an experimentalist thought not to understand mathematical physics. In the 1960s, there were a few promising indications from early satellites. But in 1973, the U.S. Navy satellite Triad carried magnetometers sensitive enough to detect these magnetic field lines, and, just as Birkeland had predicted, million-ampere currents—now called Birkeland currents—were found, exactly as his Terrella experiments had indicated. Further satellites have corroborated this, and Birkeland’s genius has finally been recognized.

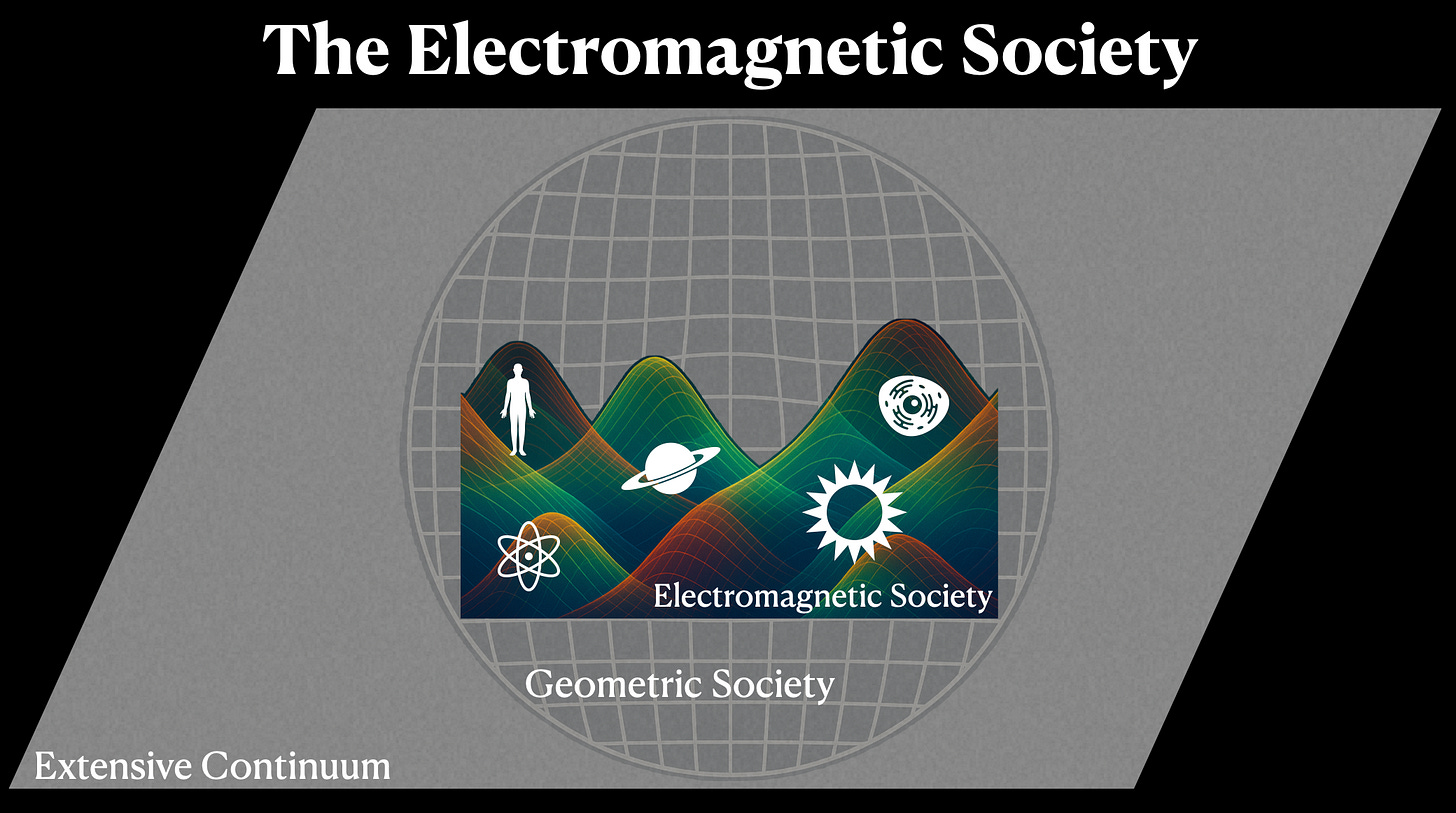

Now let’s turn to what Whitehead lays out in Process and Reality, his “essay in cosmology.” He describes reality in terms of layers—a kind of hierarchical schema of what he calls “societies,” large-scale patterns of order or habits. As we heard earlier, rather than thinking in terms of “laws,” Whitehead thought in terms of well-established habitual patterns of activity that emerge historically over the course of the universe’s evolution, with different cosmic epochs exhibiting different schemes of lawfulness.

Rather than thinking of laws as eternally and externally imposed upon physical matter, Whitehead wanted to understand how law-like behavior could emerge from the activity of the organisms composing the universe at all scales—physical, biological, and celestial. At the most general level, he refers to what he calls the “extensive continuum,” the source of non-metrical order, of pure extension—before any particular geometry, there was this extensive continuum, with very simple rules about adjacency and whole-part relationships that he considered truly metaphysical (in some sense, eternal), required for more specific forms of order.

Next, in the hierarchy, would be the “Geometrical Society of Spacetime,” where specific schemes of measurement become possible. Whitehead was a bit of a conventionalist about geometry; he didn’t think there was one geometry that definitively determined the nature of spacetime—it would depend on convention and the questions we were trying to answer, so multiple geometries could apply. Through topology and projective geometry, you can translate between different geometries.

On top of that geometric society, there is the “electromagnetic society.” While the geometric society permits multiple competing systems of measurement and congruence, with no fundamental preference, our cosmic epoch, he described, is the electromagnetic society—which resolves some ambiguities by determining a specific geometric framework, thanks to the additional physical relationships that electromagnetism provides.

The electromagnetic society, then, is a more specialized society, contained within the broader geometric society, and establishes the systematic correlations between individual “actual occasions”—Whitehead’s category for what the world is made of, from the Planck scale to the human scale, from each moment of our experience up to the stellar and galactic scale. Actual occasions of experience work themselves out, forming historical routes or societies, inheriting from the past and carrying forward certain patterns.

The dominance of electromagnetic occasions in our epoch means that physics seeks to formulate the complete systematic law governing these relationships, though this dominance is statistical rather than absolute. There are lapses. The electromagnetic society thus provides a foundational order from which more specialized societies can emerge: regular wave trains, the vibratory patterns of electromagnetism, protons, atoms, molecules, stars, galaxies, planets, living cells. You can see these more specialized forms emerging within the electromagnetic society, which provides a kind of shelter and background of order necessary for more complex organization to emerge.

Whitehead says that a cell or human organism could not survive even for a fraction of a second without the order provided by electromagnetism—and by gravity, indeed. We are nested in this series of sheltering orders, or “societies.”

Let me now talk a little about the Big Bang. Langmuir gave a talk in 1953 at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, titled “Pathological Science.” The Big Bang theory didn’t exist yet—or at least hadn’t been established among physical cosmologists—but I think his critique of what he called “pathological science,” or “the science of things that aren’t so,” applies quite well to the Big Bang. The nature of scientific paradigms is such that a model arises corresponding to a lot of available data; the data continues to pour in; there is institutional inertia; a lot of funding has been invested in a particular approach. It can take time, even as anomalies build up, for the paradigm to shift.

Of course, plasma cosmology does not have all the details worked out; it doesn’t predict everything the Big Bang predicts, and that remains to be worked out by those with more mathematical and astronomical skill than I have. Nonetheless, we should revisit what Langmuir had to say about the nature of pathological science. He listed things like ad hoc additions, endlessly adjusting free parameters. We know the Big Bang theory has had a proliferation of free parameters, adjusted as new observations come in. Originally, there were two or three parameters, but now, with the Lambda-CDM or Big Bang model, we have a dozen-plus parameters, with variants of inflation, so that the universe had to expand faster than light to account for the cosmic microwave background structure. There are hundreds of variants of the inflationary process. With each additional parameter, there is a decrease in the falsifiability of the model.

Tim Eastman refers to this idea of “post-diction”—science is supposed to be predictive, but the Big Bang model, because of its free-parameter adjustments, seems post-dictive, the inversion of proper science. You might say the Big Bang model is approaching an “epicyclic” phase of theoretical development, where mathematical sophistication masks explanatory failure. When the rotation velocity of stars at the edge of the galaxy doesn’t match what Einstein’s equations predict, that’s all right—we’ll just invent a bunch of dark matter, add it to the equations, and voilà—explanation saved. Meanwhile, as we heard, Tony Peratt has a plasma model that can achieve galactic structure without such mathematical additions.

Another issue, which Bernard Carr raised, is that the Big Bang model leaves mind out of the equation. He mentioned the anthropic principle and prefers the multiverse understanding: we just happen to be in the universe where observers are possible and have evolved, among a vast number of universes that are not so finely tuned.

Whenever we think about the early origins of the universe, and the context of the Big Bang model, there’s usually this guy blowing up a balloon to demonstrate the way galaxies expand as space expands. (If you’ve seen the American TV series King of the Hill, this is Bobby blowing up the balloon: there’s the universe expanding.) Of course, it’s not really an explosion, because space and time themselves are supposed to expand out of this process. We’re asked to imagine a beginning, but the metaphors break down—space, time, and matter themselves are in flux, and our conceptual imagination struggles to picture such origins.

Now, regarding the anthropic principle, there are different interpretations—the weak and the strong, and so on. My point with this slide is just to say: when we, as human beings, try to imagine our own cosmic origins, our tendency is to project our current form of consciousness and understanding of the physical world back in time, as if we ourselves were present at the origin to observe what was happening. There’s no way around that entirely, but in the materialist or physicalist paradigm, we often do this unconsciously. We forget that we’re always assuming an observer when we theorize about the universe, and when this is done unconsciously, I don’t think we get the right picture of what the universe might have been like at an earlier phase of its development.

It’s not only the physical nature of the universe that has evolved—from the quark-gluon sea through protons, to the first atoms, stars, galaxies—but consciousness itself has evolved. If we’re going to imagine the origins of the universe, we must also imagine how our own perceptual and reflective capacities have evolved. When we step into this inquiry in a participatory way, we recognize that a very different type of consciousness or experience may have been present at earlier phases of the evolution of the universe. What we today perceive as solid matter and the forces of physics may have been nothing like what we now experience. So when we wind the clock back, we must consider not just how the physical world has changed, but how mind has changed.

Whitehead is often described as a panexperientialist—a term coined by David Ray Griffin. Sometimes he’s just called a panpsychist. From Whitehead’s point of view, photons, electrons, stars, galaxies, single cells, and all the more complex forms of life on this planet possess some form of experience—not necessarily the self-reflexive, linguistic, symbolic consciousness of human beings, but nonetheless some form of experience. Bernard was right to associate this with the “specious present”—the living now of experience. As our physical and biological substrate becomes more complex, time dilates, the capacity for temporal depth in experience expands. In different modes of human consciousness, as Bernard explained, time dilation can increase or decrease. At the level of conscious human experience, it’s as though we can experience something approaching the fullness of time—even, in mystical states, eternity—which I would say is not the opposite of time, but the wholeness of time.

We can sit here, imagine the origins of the universe, imagine the far distant future; we have access, through our interiority, to the time dimension, which I don’t think relativistic physics, as Bernard admitted, really includes in its picture at all. Yet it’s a very important feature of reality. Time and experience are essential; if our models of physics leave them out by design, then we’re probably missing more than half the picture. We’re probably missing 99% of the picture, I would say.

So I’ll leave it at that. Hopefully I’ve raised lots of questions in your minds. Thank you

What do you think?