As the new year begins, I decided to take a look back at my speaking engagements in 2025. I turn 40 later this month, so this has been an occasion not only to recollect the recent course of my intellectual development, but to imagine how to shape what I hope will be at least another 40 years of life loving wisdom here on planet earth.

When I turned 30, I remember being pressed by friends at a surprise birthday party for “sage reflections” on my life thus far. I joked: “I guess I can’t be precocious anymore.”

Reaching life’s middle has me feeling time’s stream weaving in two directions at once. Backward with a sense of cumulative development and intensifying focus. Forward with a desire for increased ingression of theoretical form into practical activity.

When I look at my 2025 event calendar, I recall sometimes speaking with a clear thesis in hand, sometimes feeling my way toward one mid-sentence. The life of the mind is like that: structured by the crystalline clarity of already hammered out ideas, and enervated by the quicksilver confusion of creative growth into new ones. Sometimes I speak from a comfortable perch. Other times I take flight without knowing where or if I will land. I realize that I am by this point terminally tainted by my many trips on Whitehead’s speculative airplane, rising with him into the thin air of imaginative generalization before landing again for renewed application to experience. I have similarly become totally intoxicated by James’ vision of the streaming life of thought.

Like a bird’s life, [the stream of our consciousness] seems to be made of an alternation of flights and perchings. The rhythm of language expresses this, where every thought is expressed in a sentence, and every sentence closed by a period. The resting-places are usually occupied by sensorial imaginations of some sort, whose peculiarity is that they can be held before the mind for an indefinite time, and contemplated without changing; the places of flight are filled with thoughts of relations…that for the most part obtain between the matters contemplated in the periods of comparative rest.

Let us call the resting-places the ‘substantive parts,’ and the places of flight the ‘transitive parts,’ of the stream of thought. … Now it is very difficult, introspectively, to see the transitive parts for what they really are. If they are but flights to a conclusion, stopping them to look at them before the conclusion is reached is really annihilating them. … As a snow-flake crystal caught in the warm hand is no longer a crystal but a drop, so, instead of catching the feeling of relation moving to its term, we find we have caught some substantive thing, usually the last word we were pronouncing, statically taken, and with its function, tendency, and particular meaning in the sentence quite evaporated. The attempt at introspective analysis in these cases is in fact like seizing a spinning top to catch its motion, or trying to turn up the gas quickly enough to see how the darkness looks.

—William James

Principles of Psychology (1890),

“The Stream of Thought.” p. 243-244

I spent the year testing how far I can stretch the same basic claims: that reality is a participatory event, experiential all the way down; that conscious human beings are not epiphenomenal exceptions but microcosmic exemplars; and that our ecological and social crises are downstream of a deeper disease of the heart. These claims have forebears. I inherit and amplify my many process-relational and radically empirical teachers, the Romantic lineage, the anthroposophical provocation that imagination must become scientific instrument and not just literary ornament. It feels unlikely any of that is going away. But as I head into 2026 I am already noticing a shift in my center of gravity. I will continue to teach and supervise graduate students, and I assume I will continue to be asked to explain what Whitehead or Schelling or Steiner means by this or that. Alongside this sort of exegetical work, however, I am being called to step more into my own authority.

This is not by any stretch a declaration of independence from the traditions that have formed me. Far from it; I consider this shift to be a maturation in my sense of interdependence with them. For a while now, my fidelity to lineage has been fused with my own voice. I’ve never rehearsed a canon as if it were outside me but have always felt I was speaking from inside the questions that animated the thinkers I respect most.

Last January began with that exact feeling of stepping into a living conversation with immediate practical import rather than delivering a museum report. Invited to Ojai, CA to speak to the Institute of Transactional Philosophy, my talk, “From Cellular Collectives to Human Organizations,” approached “organization” not as a metaphor but as an ontological continuity across scales from cellular coordination and morphogenetic constraint to human institutions and the fragile intelligence of groups. The Institute is designed to foster the difficult art of thinking together, not just talking at one another. They take “transaction” in John Dewey and Arthur Bentley’s sense: human beings are not isolated substances interacting at a distance, as if behind veils of representation; we are composed of co-constituting events, such that knower and known, agent and environment, self and society always arise together.

In February, I interviewed philosopher of physics Ruth Kastner:

Ruth’s Possibilist Transactional Interpretation provides a way to speak about quantum reality without collapsing into either naïve realism or mystical vagary. “Transaction” in this context is not unlike Dewey and Bentley’s (which is why the Institute for Transactional Philosophy has also hosted her!). Ruth shared that she had been reading some of my work on Whitehead and wrestling with “eternal objects.” She candidly expressed concern that the term Whitehead chose risks suggesting changelessness when what her own picture requires is atemporality without stasis. I was glad for the resistance to the terminology because it names a tension I detect in Whitehead himself, who sometimes leans too eternalist while other times insisting on a two-way commerce between actuality and possibility such that eternity is said to be “enriched” by the passage of history. We next attempted to map Whitehead’s concept of concrescence onto the unitary/non-unitary split in quantum theory: unitarity as a continuum of possibility and non-unitarity as the decisive cut that yields discrete outcomes, time’s asymmetry, and an evolutionary history. We converged on the same idea of a field of weighted alternatives constrained by the past, met by a selection or creative act that cannot be derived from the story of closed, uncollapsed unitarity alone. From there we moved into the sociology of ideas: Ruth described the gatekeeping she has encountered in the physics community via dismissive claims that the transactional interpretation isn’t really a theory unless it offers a novel experimentum crucis to establish its correctness. This is a double standard, a symptom of paradigm entrenchment. It confuses the all-important distinction between know-how (instrumental knowledge affording correct predictions) and know-what (theoretical understanding of what is occurring in the experiments). To dismiss the Possibilist Transactional Interpretation because it suggests no new experiments is to forget the problem at hand. We don’t need better recipes for making predictions. The quantum formalism is already the most accurate in the history of science. The problem is that we have no idea what it means, ie, what is going on behind the scenes of our measurements. That is what Ruth’s theory offers. We paralleled this with sociological dynamics at play in consciousness studies, where instrumentalism and epistemology-first habits of thought shrink the target until nothing needs explaining, mistaking the limits of scientific measurability for the limits of ontology. I pressed the point that metaphysics isn’t optional because empirical science itself presupposes a world with stable patterns that make induction possible. As soon as you ask “how is inductive generalization possible?” you are already doing metaphysics.

In March, I attempted to articulate a participatory cosmology that could speak to scientists and theologians without alienating either. In my lecture “Science and Religion in a Participatory Cosmos” for the Center for Christogenesis, I refused the usual détente where science finds facts and religion defends values. I leaned instead into an older sacred sense of what is meant by Kosmos: a beautifully patterned whole whose intelligibility cannot be exhausted by measurement and calculation. For the Center, deeply influenced by Jesuit Paleontologist and evolutionary theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, “Christ” is not a tribal password but a cosmic principle, a name for the mysterious lure of Omega goading the universe into greater complexity and consciousness. I argued that the modern split between matter and meaning is not only philosophically incoherent, it is psychosocially and ecologically catastrophic. If modern civilization tells itself that all that really counts is what can be counted, it should come as no surprise that it treats forests, oceans, human and all living communities as raw material to be exploited.

Later in March I spoke at one of Limicon’s sessions, “Realizing the Biosphere,” joined Layman Pascal and Brendan Graham Dempsey, pivoting from physical transaction back into ecological enculturation. The panel title already carries the double meaning: “realizing” as understanding, and “realizing” as making real, embodying, enacting. I pushed the thought that we don’t simply live on a biosphere like tenants on a property. The biosphere lives through us. The noosphere, if it means anything, is not a shiny techno-utopian layer floating above nature but the biosphere waking up to itself in humanity’s reflective, symbolic, increasingly technologically mediated consciousness. This realization can move either toward intensified communion, or toward intensified dissociation. The event itself, with its particular mix of internet-native intellectual culture (“the liminal web”) and earnest cosmological hunger, sharpened my sense that the growing para-academic, metamodern, integral, “big picture” community of communities is at its best when it does not confuse syntheses with slogans. A mature integral philosophy can metabolize complexity without turning it into brand identity.

Early April brought a change of pace, dropping me into a more contemplative mode of inquiry. I spoke with Orland Bishop for a PCC Forum event hosted by my philosophy department at CIIS: “Sacred Hospitality and the Dynamics of Initiation.”

Orland speaks from out of a lived spiritual practice that does not need academic permission to acknowledge the subtler realities of human coexistence. Our conversation pulled me to consider the ethical and interpersonal implications of a participatory cosmology. Hospitality is not politeness. It is an ontological posture: the capacity to receive what is other without reducing it to ourselves, to hold moral tension without rushing to scapegoat, to let initiation be something more than another self-help retreat or personal growth workshop. The Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness (PCC) program consists of students and faculty who are trying to reconcile intellectual rigor with spiritual seriousness. Joining in dialogue with them and Orland, he felt like a kind of tuning fork amplifying our resolve.

April brought me to the University of Exeter for the UK’s biggest psychedelic conference: Breaking Convention: “Psychedelic Realism, or What Happens When You Mix Psychedelics and Philosophy.”

I’ve grown increasingly impatient with the framing that treats psychedelics as either mere hallucinogens or as automatic revelation machines. I tried to articulate something more, well, realistic: that psychedelic experience can be a mode of contact with the real, but only if we develop better onto-epistemic and ethical techniques for interpreting and integrating it. “Realism” here does not mean dogmatic certainty about extra-mental entities or how to navigate already objectified territories. It means refusing the modern reflex that collapses consciousness into a private cinema, reduces the physical world to meaningless mathematical abstraction, and then treats any deviation from consensus perception as an opportunity for psychiatric diagnosis. The Breaking Convention milieu is uniquely suited to this argument because it contains both extremes: the romantic hunger for cosmic meaning and the skeptical demand for scientific evidence.

A few days later in London, Matreyabandhu hosted me at the London Buddhist Centre for a conversation later titled “Reality is a Process.”

Here, as in my dialogue with Orland, relational metaphysics became contemplative. Having identified as a practitioner myself at an earlier phase of life, I approach Buddhism with great care. It is an easy ally for process thought, but the comparison can become stale and flattening if differences are politely ignored. The conversation let me emphasize what feels most alive to me in the resonance, for example: impermanence not as a lamentable fact but as the very condition of value; the self not as a substance but as a flowing pattern of inheritance and aim; compassion not as high-minded sentiment but as realistic response to the intradependence of all becomings. The London Buddhist Centre is not an abstract debate club. It’s a place for people who have committed their lives to meditative practice.

I returned to Oakland in late April to give a talk for the UTOK (Unified Theory of Knowledge) Conference on Consciousness hosted by Gregg Henriques and John Vervaeke. On a panel with Michael Levin and Bonnitta Roy, I delivered a lecture titled “An Anthropocosmic Approach to the Nature of Consciousness.” This talk was me thinking out loud, wandering along the edges of many disciplinary languages. Levin’s laboratory work makes it increasingly hard to keep repeating the old story that mind begins in brains. Roy has her own wildly creative ways of refusing that reduction. My contribution was “anthropocosmic”: consciousness not as an exclusively human possession but grows along a cosmic continuum, with the human as a unique intensification that carries potentially universal responsibility. I tried to hold together the demands for empirical groundedness and metaphysical imagination. We have data that doesn’t fit our inherited categories. The question is whether we continue to ignore the anomalous data to save the categories, or revise the categories to honor the data. As I put it in my talk:

For me, within this anthropocosmic context, rationality involves building proportional analogies between what we know well and what we know less well. That entails a certain anthropocentrism in our explanations, yet an anthropocosmic perspective pushes us beyond common-sense human categories into the weirdness of how the rest of nature does its own thing. We should see ourselves as exemplifications of cosmogenesis rather than improbable exceptions to it. It turns out that we can learn more about what it means to be human by getting out of our heads.

May had me driving an hour and a half north to Healdsburg, CA for Edge Esmeralda’s Consciousness week. Invited to deliver a talk at the last minute, I came up with the title: “Imago Machinae: Made in the Image of Our Machines.”

AI discourse has become a kind of cultural weather system: hype fronts, doom fronts, sudden lightning flashes of sober critical reflection followed quickly by gusts of utopian optimism. I tried to flip the framing before an audience (mostly engineers and investors) that I wasn’t sure would be receptive. The issue is not whether machines will become conscious, but what machines are doing to our consciousness: to our imagination of divinity, to our sense of what a person is, to our habits of attention and our ethical evaluation. Instead of pretending technology is simply an externalization of human will, I explored what it might mean to acknowledge the ways our machines have always already been redesigning us. In a setting of builders and techno-optimists, I tried to speak as a friendly irritant, a philosopher as grit in the oyster:

Human intelligence has always been artificial in this sense: we think with our tools. Obsidian blades, bone flutes, alphabets, typewriters, transistors. All are part of our extended mind. We do not merely use them. We become them; they become us. We might wonder at this point: who is inventing whom? We must attend as carefully as we can to the nature of this loopiness, lest we lose our way.

In June, I drove south to Pomona College in Claremont, CA, where the Center for Process Studies hosted a conference on ecological civilization: “Is It Too Late?” My talk was titled “Whitehead’s ‘Foresight,’ Or How Process Philosophy Can Shape the Business Mind of the Future.”

The “ecological civilization” conversation tends to happen among the already converted. The business world is often treated as the villain or at best as a neutral mechanism for meeting human needs and wants. I wanted to reintroduce the business mind as itself an important form of imagination. In all our commercial activities we operate with metaphysical assumptions about value, time, risk, nature, and persons. If we alter those assumptions, we can change what becomes thinkable inside a corporation. We can change how corporations behave. Whitehead’s “foresight” is not merely about prediction. It is a disciplined sensitivity to the way the future is lured into the present through the selective patterns of attention that guide decision-making. This talk reflects my increasing desire to bring philosophical imagination to bear on economic and political institutions.

July was probably the busiest month of my professional life. It began with “Revitalizing Biophilosophy,” an online conference I co-organized with my colleague Spyridon Koutroufinis. It was technical, interdisciplinary, and full of unresolved tensions. Speakers included Timothy Jackson, Michael Levin, Terrence Deacon, and Jack Bagby. My talk, “Romanticizing Evolution with Schelling, Peirce, and Whitehead,” previewed some ideas I’d share a week later at a conference in Germany (more on that below):

A week later, I traveled to Tübingen, Germany to speak at the “Cognizing Life”conference hosted by Christoph Hueck. I was delighted to speak after Dalia Nassar, whose books and articles have been truly formative for my understanding of Schelling’s and Goethe’s Naturphilosophie, and Daniel Nicholson, whose process philosophy of biology and recent research on organicism converges with my own. My talk (“Whitehead’s Organic Realism and the Return of Organic Science”) was, in a sense, a travelogue through a lineage: Kant’s epigenesis of reason, Schelling’s refusal to leave nature outside thought (or thought outside nature!), Goethe’s participatory method of exact sensorial imagination, Steiner’s wager that imagination can become a supersensible organ of cognition, and Whitehead’s generalization of the creative act of experience into a cosmological principle.

But I wasn’t just doing intellectual history. I was attempting to make a claim about method in the philosophy of nature. Evolution is not a mechanism or reducible to the Darwinian principle of variation under differential selection. Evolution is a creatively purposive process. And to understand it, we need to cultivate the onto-epistemics of participation, a mode of consciousness that modern epistemologies of representation have trained us to dismiss. I admit it was a thrill to stand in Tübingen speaking Romantic science back into a German philosophical milieu, with the ghosts of Naturphilosophie listening a few blocks away at the famous Tübingen Stift where Hölderlin, Schelling, and Hegel were roommates.

From Tübingen I traveled back to England. While there between conferences, I took a pilgrimage to St. Peter’s Church in Firle, Sussex, walking a segment of the Old Wayand staying the night in the church at the invitation of the vicar. That night, which happened to be Mary Magdalene’s Feast Day, left me with a sense of both transcendent grief and divine gratitude. Many of the verses in my prayer-poem “Sancta Maria Magdalena” came to me that night. The poem, while not a conference talk, still belongs in the year’s speaking arc because it signals something I’ll be doing more consciously in 2026: attempting to let philosophy and prayer, erudition and eros, scholarship and devotion be free from compartmentalization. A living philosophy has to be able to kneel. It has to be able to sing and dance.

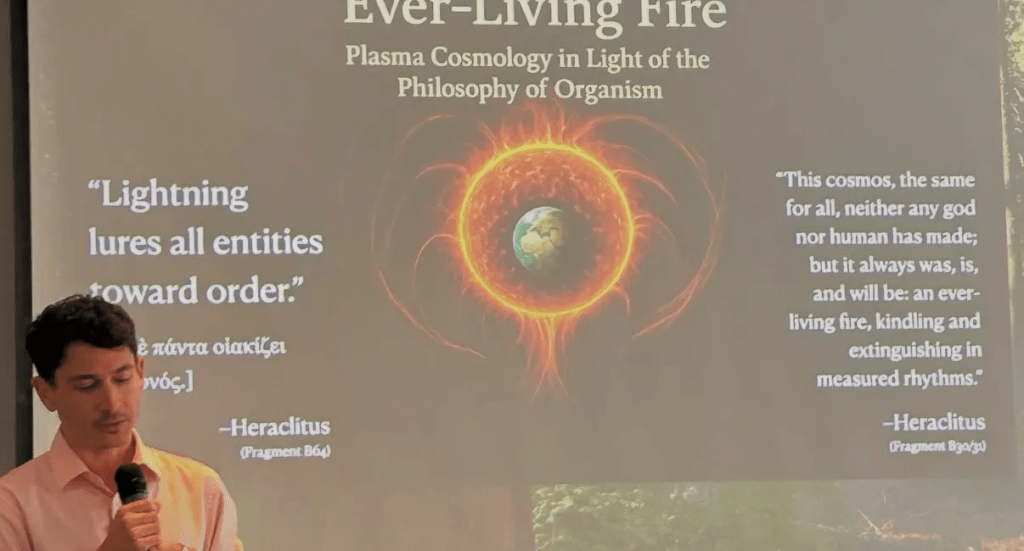

Late July brought me back to University of Exeter for a conference on Process Philosophy, Plasma Cosmology, and Transpersonal Psychology, again hosted by the Center for Process Studies. My presentation, “Ever-Living Fire: Process Philosophy and Plasma Cosmology,” was an experiment in cosmological imagination. Plasma cosmology sits outside the mainstream of astrophysics, and transpersonal psychology still embarrasses many academics. Yet the workshop gathered serious scholars and scientists who were willing to explore whether our standard cosmology is missing something fundamental. I leaned into the thought that plasma is not merely the fourth state of matter, but might be closer to a kind of prima materia, a living medium of fields and filaments, an electromagnetic fabric that makes clear why the notion of “empty space” is a conceptual mistake. I unpacked Whitehead’s account of our cosmic epoch as “a society of electromagnetic occasions” and speculated about how gravity and “levity” may be co-organizing our cosmos.

I flew back to the USA the first week of August, stopping in Charlottesville, Virginia to visit the University of Virginia’s Department of Perceptual Studies, where I participated in Edward Kelly’s “Solving the Mystery of Consciousness” theory meeting. Together with other philosophers, physicists, and psi researchers, I spent a week carefully engaging with ongoing research programs and unresolved anomalies. The task at hand was to develop a metaphysics that might do justice to the accumulated body of parapsychological data. I delivered a lecture on the relevance of Schelling’s evolutionary panentheism to psi research and contributed what I could to the discussion of the compatibility of Whitehead’s process-relational ontology with precognition. I recapped the discussion in the essay, “Notes from the Edge of the Ordinary.” The group is working on a book that I hope comes to fruition later this year.

In September, I flew to Aspen, CO to speak at the “Frontiers of Knowledge” event at Wheeler Opera House. I joined my friend and colleague, the astrobiologist Bruce Damer to discuss “The Origin of Life.” I found myself speaking to a broad public with a different kind of confidence, again at the edge of my own understanding. I framed life not as a freak chemical coincidence but as an evolutionary inevitability, an expression of matter’s own organizational eros and desire to intensify. I spoke to the inadequacy of mechanistic framings, the need to treat love as more than a private emotion, and the sense that evolution is not only blind natural selection but creative value-formation. The wealthy Aspen audience brought genuine curiosity, but also left me feeling how urgently our culture needs a new story of life that speaks across class divides. I believe this nascent mode of consciousness is transformative even and perhaps especially for those struggling just to make ends meet. It does not on its own resolve economic injustices, but it sets a more viable context for that important work.

Back at CIIS later in September, I spoke at the conference “Forever Jung?: C.G. Jung’s Continued Relevance During Challenging Times,” hosted by the East-West Psychology Department. My talk was titled “Remembering the Repressed with Carl Jung and Rudolf Steiner.” Jung and Steiner share an inconvenient message for modernity: what you repress does not disappear; it returns as symptom, projection, and personal and collective fate. I brought Jung’s depth psychology into conversation with Steiner’s spiritual science around the problem of evil. CIIS is one of the few places where these lineages can still speak in public without being instantly caricatured. In that sense, the talk was also an institutional gratitude-practice. And it was politically urgent: if we cannot learn to remember what we collectively disavow, we will keep making enemies out of our own shadows.

In October, I joined my philosophy students and fellow faculty on retreat at Bishop’s Ranch in Healdsburg again. My colleague Jacob Sherman and I dialogued on the relationship between philosophy and religion in the West: “Metaphysics and Theology.” As much as he values Whitehead’s philosophy, we zeroed in on some hangups that Jacob has with process theology. We did not resolve the issue, but I tried to draw us closer with the following thought:

I think in the Western tradition, God has been understood as that which has necessary existence. And part of the problem with onto-theology (as the Kant and Heidegger critique has it) has to do with that idea of necessary existence. And Whitehead has a very, I think, cool way of getting around this issue where he says God is metaphysically contingent—which is to say, God is an accident of Creativity, not exactly caused by Creativity—an accident of Creativity. So God is metaphysically contingent but categorically necessary, which is to say: for us, as finite, reflective creatures, we can’t help but think Creativity through God. Very subtle distinction, but I think it’s important.

In December I closed the year with a triad of talks. First, I was invited to contribute to the Symposium on Platonic Space organized by Michael Levin and Hananel Hazan. My talk was titled “Whitehead on the Ingression of Novel Form: Toward a New Formal Causality in the Life Sciences.” I attempted to give “form” back its metaphysical dignity without reverting to static essences. Whitehead’s concept of “ingression” lets us speak about forms (or “eternal objects”) as real potentials that partake in historic becoming. The new formal causality I am after is an attempt to say that efficient causes alone do not account for the emergence of organized novelty, and that biology is begging for a better metaphysical vocabulary.

Next, I delivered a lecture for the Cobb Institute’s “Process Explorations” series: “Romantic Imagination and the Recovery of Nature’s Intrinsic Value.” I drew on Whitehead and Owen Barfield to offer a diagnosis of modernity’s disease of perception. I tried to say plainly that the ecological crisis is not only about carbon emissions or energy policy. It is a crisis of imagination, a contraction of perception that makes nature appear valueless and therefore expendable. Whitehead’s critique of the bifurcation of nature and Barfield’s account of evolutionary participation helped me argue that imagination is not a source of subjective additions but a means of perceiving and co-creating forms of value.

Finally, Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Evolution of Spirituality hosted the 100 Years Rudolf Steiner conference. My talk framed Steiner through a Whiteheadian lens to clarify what, in the context of an academic conference on his work, feels most philosophically provocative: the claim that imagination can become participatory organ of cognition. Steiner’s spiritual science, approached open-mindedly, is not an escape from empiricism but a demand to deepen it.

I will always think, write, and speak as someone who has inherited a tradition and who belongs in a lineage. I don’t feel this as a burden. Far from it, I feel buoyed. But now I’m feeling the call to take responsibility for what that lineage is asking to become through me.

In 2026 I want to risk a new kind of directness with fewer guided tours through other people’s ideas, more open air construction in the wild fields where metaphysics meets practice, where cosmology becomes ethics, where ideas are tested not only by argument but by the quality of attention and relationship they make possible.

What do you think?