Today’s New York Times featured a profile on my friend, mycologist Merlin Sheldrake. In addition to discussing the philosophical implications of his scientific research, the article shares a bit about his magical childhood and fascinating family. Do give it a read.

Merlin was kind enough to mention a collaboration with me to sort out the various conceptual tendrils linking his mycological research to my work on Whiteheadian metaphysics. An editor from the NYT had reached out to me a few weeks ago to fact check that, indeed, Whitehead believed “everything in the universe — people, cats, planets, atoms, electrons — can ‘experience’ existence.”.

I thought Jennifer Kahn did a marvelous job profiling Merlin, but in the final lines of her article she seemed to me to miss an opportunity to grok the deeper implications of his work. She writes:

“Occasionally I caught myself daydreaming about a world in which fungi, not humans, had evolved to be the dominant species. What would such a world be like, so full of shared senses and experiences? Would a fungus look down on the disturbing isolation of mammalian life, where perceptions and thoughts were limited to a single small body and brain? It was a dizzying idea but also enticing. And when the daydream would fade, returning me to my solitary, disconnected body, I would sometimes find myself thinking: Wait. Please stay. Can I join you?”

First, I know many microbiologists who would dispute the idea that humans are the dominant species. But let’s put that aside. It’s true that mammals are organized in such a way that our individuality is more strongly emphasized. Plants, microorganisms, and of course, fungi, are far more decentralized. But I question whether our perceptions and thoughts are really limited to a single small body and brain, or whether this sense of limitation is mostly a culturally constructed story so deeply engrained that perception itself comes to conform with it. This is what we mean by a world view, after all.

Whitehead provides us with a way of taking seriously the possibility that our normal (for modern, western people) sensory experience of being isolated in our skulls peering out at an separate extended world of colored surfaces is in fact the daydream that, with practice (or a decent dose of psilocybin!), may fade to reveal a profound connectivity pulsing just below the surface. Relevant here is Whitehead’s account of perception in terms of two basic modes (only separable for the purposes of intellectual analysis): what he calls “presentational immediacy” and “causal efficacy.” The former is what we normally call “sense perception,” which philosophers from Hume to Kant to Russell argued was the only means of contact human beings have with the outside world. It is experience of patches of color geometrically arrayed with no meaningful relations to one another. Relations are said to be added later, by the associative machinery of thought. Whitehead says this is nonsense, putting everything the wrong way round. Relations come first—specifically, causal relations, which in our case are felt not primarily via sense perception but as what he refers to as “bodily reception,” or again as “vector-feelings,” “emotional tones,” or “prehensions.”

“We find ourselves in the double role of agents and patients in a common world, and the conscious recognition of impressions of sensation is the work of sophisticated elaboration…A young man does not initiate his experience by dancing with impressions of sensation, and then proceed to conjecture a partner. His experience takes the converse route. The unempirical character of the philosophical school derived from Hume cannot be too often insisted upon. The true empirical doctrine is that physical feelings are in their origin vectors, and that the genetic process of concrescence introduces the elements which emphasize privacy.” (Whitehead, Process and Reality [1929/1978], 315-316)

The elements emphasizing privacy culminate in our conscious experience of perception in the mode of presentational immediacy, which functions as a kind of dashboard enabling our practical maneuvering in the world of other middle-sized bodies. Whitehead says presentational immediacy, with its distinct edges and geometrical clarity, is the basis for all scientific measurement. But it is really just a useful dashboard, that is, an appearance. Under the hood, reality is a “blooming, buzzing confusion” as William James famously put it, a complex web of subtle and not so subtle causal vectors that weave the world together into a nexus of feeling. Thankfully, privacy is not a total delusion in Whitehead’s world; but the private subjective perch achieved by the satisfaction of what he calls the process of concrescence (i.e., the growing together of public feelings into a new private subject) is, first of all, a perspective of the whole universe, and secondly, once achieved, perishes back into the universe out of which it arose, becoming once again a public “superject” whose feelings are transmitted throughout the network of subsequently concrescing creatures.

So, my reply to Kahn’s last lines is just to say, “Hey, maybe you can join the fungi! Maybe you already do live in that kind of world.”

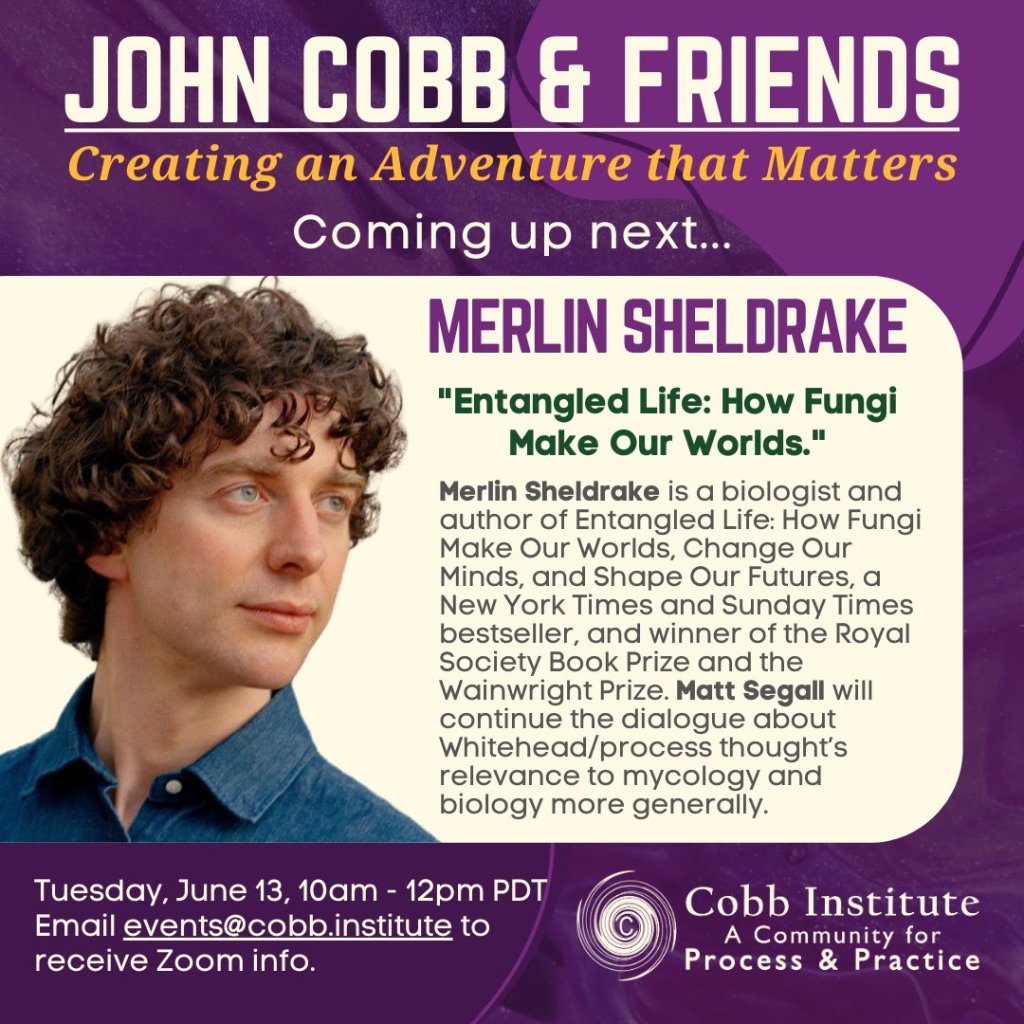

For those interested to hear more about the sorts of ideas Merlin and I have found ourselves tangled up with, I’ll be joining him for a Zoom dialogue hosted by the Science Advisory Commitee of the Cobb Institute next week. Email events@cobb.institute for the link.

Leave a reply to Evolutionary Development Leader Cancel reply