I just finished listening (at x2 speed!) to

Tyler Goldstein’s very long but also very insightful YouTube commentary (see above) responding to my recent dialogue with Curt Jaimungal (“What is the Human Being?”). Tyler had never heard of me or Whitehead before, nor had I heard of Tyler’s “theory of every0ne.” From the sound of it there are a ton of convergent ideas (maybe even more than Tyler realizes!) but also probably some very interesting and hopefully edifying differences. I’m grateful to him for taking the time to respond with such care and insight.

To save me from the overwhelming task of trying to summarize Tyler’s five hour (!) video, I fed the 47,000 word transcript into ChatGPT and asked it to provide a detailed summary (I made a few corrections and additions):

The transcript of Tyler Goldstein’s talk, referencing a video featuring Matthew Segall and Curt Jaimungal, covers extensive philosophical territory, focusing on metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, and process philosophy. Below is a detailed summary:

1. Overview and Context:

• Tyler Goldstein discusses a conversation on Curt Jaimungal’s Theories of Everything channel featuring Matthew Segall. Segall, a philosopher with expertise in cosmology and consciousness, explored process philosophy and its implications for metaphysics and modern scientific thought.

2. Process Philosophy and Ontology:

• The discussion emphasizes the evolution of philosophical thought, contrasting the Platonic view of universals with nominalism’s perspective that universals are merely names. Segall ties these historical debates to theological concerns, such as the limits of divine omnipotence.

• Goldstein engages with Segall’s ideas, particularly the Platonic notion that universals have an independent existence, contrasting it with nominalism’s focus on particularities. Segall points to the example of “twoness” as an irreducibly real universal, while Goldstein adds that “one” may be an even better example.

3. Consciousness and Sentience:

• The talk delves into Descartes’ dualism, critiquing his dismissal of animals’ sentience. Segall challenges the Cartesian view that animals are mere machines devoid of inner experience, advocating for a broader understanding of sentience.

• Goldstein builds on this, proposing that sentience, defined as feeling or experiencing, is fundamental to being. He contrasts “I think, therefore I am” with “I feel, therefore I am,” suggesting that feeling is a more primal and universal basis for existence.

4. Kantian Epistemology:

• Goldstein highlights Kant’s shift from ontology to epistemology, focusing on how we know rather than what exists. This aligns with Kant’s “Copernican Revolution,” where he posits that the structure of our minds shapes our experiences of space, time, and causality.

• Kant’s critique of metaphysical dogmatism and his reconciliation of empirical observation with a priori knowledge is discussed as a pivotal moment in philosophy.

5. Whitehead’s Process Philosophy:

• Segall introduces Whitehead’s concept of “actual occasions,” suggesting that reality is composed of events or processes rather than static substances. This idea is connected to the notion of a dynamic, interconnected universe.

• Goldstein critiques the terminology of “occasions,” arguing that “experiencers” or “minds” better capture the fundamental nature of existence as relational and dynamic.

6. Application to Modern Theories:

• Goldstein ties these philosophical insights to contemporary metaphysical debates, including Steven Wolfram’s “Observer Theory.” He suggests that the laws of physics and the structure of reality are shaped by the nature of observation and the perceiving mind.

7. Critique of Academic Philosophy:

• Goldstein criticizes the prioritization of secondhand information over firsthand experience in academic philosophy, warning that this leads to a detachment from fundamental truths. He advocates for a philosophy rooted in lived experience and personal insight.

8. Sentient Singularity Theory:

• Goldstein elaborates on his “Sentient Singularity Theory,” positing that existence is fundamentally about relational sentience. He emphasizes the importance of language and metaphysical framing, advocating for a shift from a “Theory of Everything” to a “Theory of Every0ne” that centers on the relational and experiential aspects of being.

The talk weaves together historical philosophical developments, critiques of modern academic trends, and speculative metaphysics, providing a rich exploration of how ancient and contemporary ideas intersect in understanding consciousness, existence, and the nature of reality.

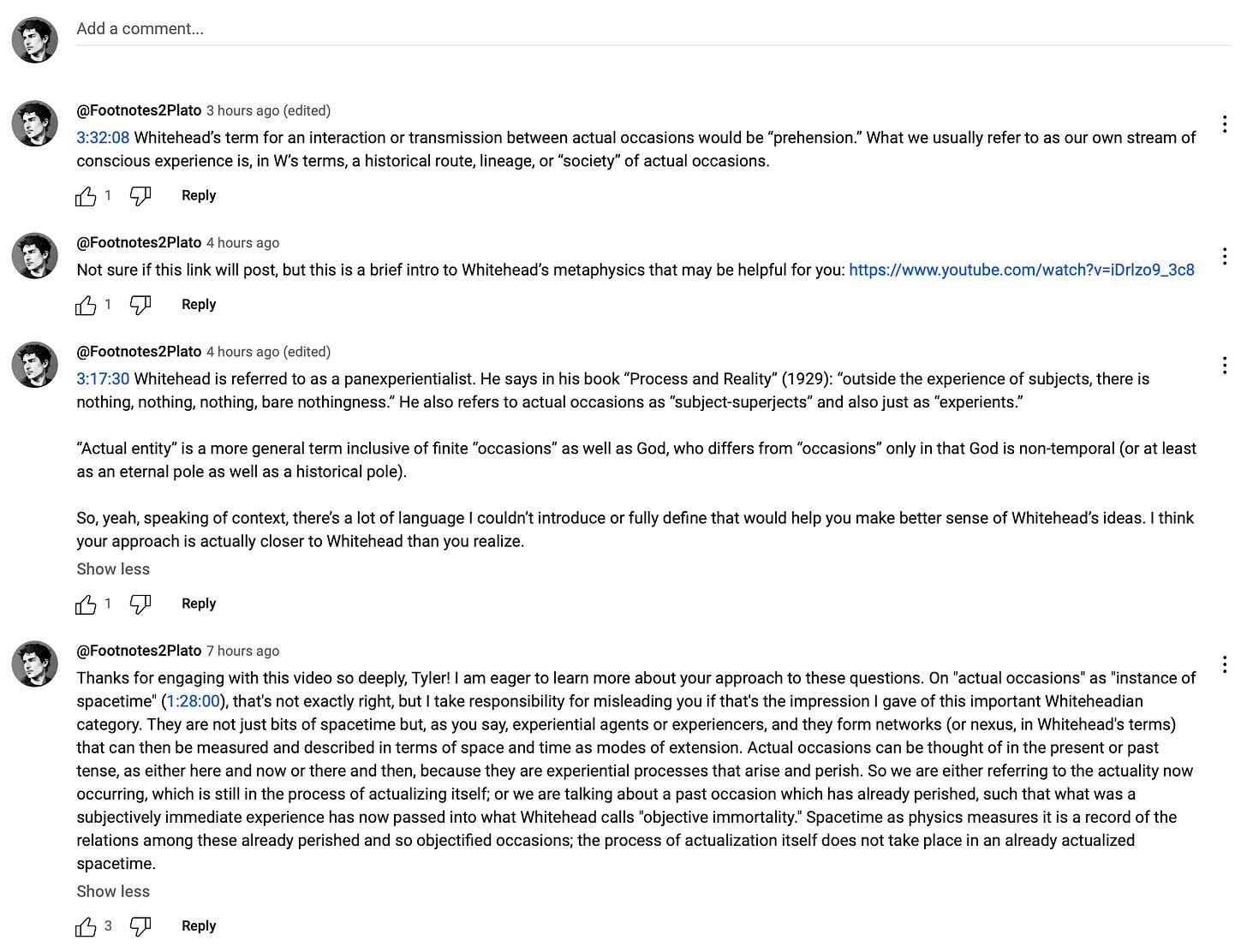

I made a few comments under Tyler’s YouTube video, which I’ll share below:

It is clear that Tyler and I share many core intuitions about the nature of reality and our role as human participants. I suspect that as we iron out the linguistic wrinkles in our means of expressing these intuitions, we will discover even more resonances.

I want to quote at length from the first part of Whitehead’s magnum opus, Process and Reality (1929). This is to help make clear what is at stake in the sort of metaphysical meeting of minds that is occurring in dialogues like this. From pgs. 8-12:

Philosophy has been haunted by the unfortunate notion that its method is dogmatically to indicate premises which are severally clear, distinct, and certain; and to erect upon those premises a deductive system of thought.

But the accurate expression of the final generalities is the goal of discussion and not its origin. Philosophy has been misled by the example of mathematics; and even in mathematics the statement of the ultimate logical principles is beset with difficulties, as yet insuperable. The verification of a rationalistic scheme is to be sought in its general success, and not in the peculiar certainty, or initial clarity, of its first principles. In this connection the misuse of the ex absurdoargument has to be noted; much philosophical reasoning is vitiated by it. The only logical conclusion to be drawn, when a contradiction issues from a train of reasoning, is that at least one of the premises involved in the inference is false. It is rashly assumed without further question that the peccant premise can at once be located. In mathematics this assumption is often justified, and philosophers have been thereby misled. But in the absence of a well-defined categoreal scheme of entities, issuing in a satisfactory metaphysical system, every premise in a philosophical argument is under suspicion.

Philosophy will not regain its proper status until the gradual elaboration of categoreal schemes, definitely stated at each stage of progress, is recognized as its proper objective. There may be rival schemes, inconsistent among themselves; each with its own merits and its own failures. It will then be the purpose of research to conciliate the differences. Metaphysical categories are not dogmatic statements of the obvious; they are tentative formulations of the ultimate generalities.

If we consider any scheme of philosophic categories as one complex assertion, and apply to it the logician’s alternative, true or false, the answer must be that the scheme is false. The same answer must be given to a like question respecting the existing formulated principles of any science.

The scheme is true with unformulated qualifications, exceptions, limitations, and new interpretations in terms of more general notions. We do not yet know how to recast the scheme into a logical truth. But the scheme is a matrix from which true propositions applicable to particular circumstances can be derived. We can at present only trust our trained instincts

One place where we may differ even after the initial translation work is done, as to the discrimination of the circumstances in respect to which the scheme is valid.

The use of such a matrix is to argue from it boldly and with rigid logic. The scheme should therefore be stated with the utmost precision and definiteness, to allow of such argumentation. The conclusion of the argument should then be confronted with circumstances to which it should apply.

The primary advantage thus gained is that experience is not interrogated with the benumbing repression of common sense. The observation acquires an enhanced penetration by reason of the expectation evoked by the conclusion of the argument. The outcome from this procedure takes one of three forms: (i) the conclusion may agree with the observed facts; (ii) the conclusion may exhibit general agreement, with disagreement in detail; (iii) the conclusion may be in complete disagreement with† the facts.

In the first case, the facts are known with more adequacy and the applicability of the system to the world has been elucidated. In the second case, criticisms of the observation of the facts and of the details of the scheme are both required. The history of thought shows that false interpretations of observed facts enter into the records of their observation. Thus both theory, and received notions as to fact, are in doubt. In the third case, a fundamental reorganization of theory is required either by way of limiting it to some special province, or by way of entire abandonment of its main categories of thought.

After the initial basis of a rational life, with a civilized language, has been laid, all productive thought has proceeded either by the poetic insight of artists, or by the imaginative elaboration of schemes of thought capable of utilization as logical premises. In some measure or other, progress is always a transcendence of what is obvious.

Rationalism never shakes off its status of an experimental adventure. The combined influences of mathematics and religion, which have so greatly contributed to the rise of philosophy, have also had the unfortunate effect of yoking it with static dogmatism. Rationalism is an adventure in the clarification of thought, progressive and never final. But it is an adventure in which even partial success has importance.

…

Every science must devise its own instruments. The tool required for philosophy is language. Thus philosophy redesigns language in the same way that, in a physical science, pre-existing appliances are redesigned. It is exactly at this point that the appeal to facts is a difficult operation. This appeal is not solely to the expression of the facts in current verbal statements. The adequacy of such sentences is the main question at issue. It is true that the general agreement of mankind as to experienced facts is best expressed in language. But the language of literature breaks down precisely at the task of expressing in explicit form the larger generalities—the very generalities which metaphysics seeks to express.

The point is that every proposition refers to a universe exhibiting some general systematic metaphysical character. Apart from this background, the separate entities which go to form the proposition, and the proposition as a whole, are without determinate character. Nothing has been defined, because every definite entity requires a systematic universe to supply its requisite status. Thus every proposition proposing a fact must, in its complete analysis, propose the general character of the universe required for that fact. There are no self-sustained facts, floating in nonentity. This doctrine, of the impossibility of tearing a proposition from its systematic context in the actual world, is a direct consequence of the fourth and the twentieth of the fundamental categoreal explanations which we shall be engaged in expanding and illustrating. A proposition can embody partial truth because it only demands a certain type of systematic environment, which is presupposed in its meaning. It does not refer to the universe in all its detail.

One practical aim of metaphysics is the accurate analysis of propositions; not merely of metaphysical propositions, but of quite ordinary propositions such as ‘There is beef for dinner today,’ and ‘Socrates is mortal.’ The one genus of facts which constitutes the field of some special science requires some common metaphysical presupposition respecting the universe. It is merely credulous to accept verbal phrases as adequate statements of propositions. The distinction between verbal phrases and complete propositions is one of the reasons why the logicians’ rigid alternative, ‘true or false,’ is so largely irrelevant for the pursuit of knowledge.

The excessive trust in linguistic phrases has been the well-known reason vitiating so much of the philosophy and physics among the Greeks and among the mediaeval thinkers who continued the Greek traditions. For example John Stuart Mill writes:

- They [the Greeks] had great difficulty in distinguishing between things which their language confounded, or in putting mentally together things which it distinguished and could hardly combine the objects in nature into any classes but those which were made for them by the popular phrases of their own country; or at least could not help fancying those classes to be natural, and all others arbitrary and artificial. Accordingly, scientific investigation among the Greek schools of speculation and their followers in the Middle Ages, was little more than a mere sifting and analysing of the notions attached to common language. They thought that by determining the meaning of words they could become acquainted with facts.

Mill then proceeds to quote from Whewell a paragraph illustrating the same weakness of Greek thought.

But neither Mill, nor Whewell, tracks this difficulty about language down to its sources. They both presuppose that language does enunciate well-defined propositions. This is quite untrue. Language is thoroughly indeterminate, by reason of the fact that every occurrence presupposes some systematic type of environment.

For example, the word ‘Socrates,’ referring to the philosopher, in one sentence may stand for an entity presupposing a more closely defined background than the word ‘Socrates,’ with the same reference, in another sentence. The word ‘mortal’ affords an analogous possibility. A precise language must await a completed metaphysical knowledge.

The technical language of philosophy represents attempts of various schools of thought to obtain explicit expression of general ideas presupposed by the facts of experience. It follows that any novelty in metaphysical doctrines exhibits some measure of disagreement with statements of the facts to be found in current philosophical literature. The extent of disagreement measures the extent of metaphysical divergence. It is, therefore, no valid criticism on one metaphysical school to point out that its doctrines do not follow from the verbal expression of the facts accepted by another school. The whole contention is that the doctrines in question supply a closer approach to fully expressed propositions.

I share these paragraphs from Whitehead’s book to emphasize the importance of a theme Tyler continually returned to in his commentary: the words we use to express our ideas are not arbitrary labels. And yet, it often happens that we may misunderstand one another simply because, despite sharing a silent because direct intellectual feeling of the same proposition, the words we pronounce to convey those feelings do not initially rhyme.

Metaphysics is a mode of human being. If Aristotle was right, it is not just any mode but is essential to our human way of being. We are the beings who wonder, not just about this or that particular fact, but about existence as such. Metaphysics is what happens when we try to make linguistic sense of the primal emotion of amazement. Wonder is potentially felt by human beings at every stage of life (including death): by infants as they take their first breath and elders as they take their last, by children and adults alike who open themselves fully to the open secret displayed for us in the sight of the starry heavens above us. This feeling can be awesome or awful, beautiful or sublime, empowering or shattering. Language is our instrument for making music of what might otherwise be mayhem, our tool for making tools, our medium of metaphoric passage between the obvious and the unknown, our traceship for drawing forth new worlds, our memory map to orient us amidst the open ocean of Whitehead’s “creative advance” (or what I call chaosmogenesis in my last book).

At the end of the day, all my sentences are the collective achievement of a historical route of occasions of experience that I retroactively identify as mine all attempting to convey meanings I cannot claim to know in advance and on occasion hardly understand upon uttering. I hear myself say things, reflect, and agree or disagree. Sometimes I hear myself say things, and realize I didn’t quite say it right. I correct myself. In dialogue, we correct each other, or at least corral our meanings closer to a shared sense of conceptually prehending the same eternal objects and logical subjects (ie, the same “propositions” in Whitehead’s sense). That is to say, communication about metaphysical matters presupposes a shared realm of ideas can be felt by our minds and then indicated with our words. We each have embodied perspectives on the physical world, unique perceptual points of view on what happens in the pluriverse. Learning to speak a language is not just about memorization but requires poetry and creative risk. We never entirely shake off our individual idiosyncrasies even after mastering grammatical expectations. But as we come to share a language we are also engaged in a coordination operation, gradually approaching agreement about the universe of ideas we feel by way of nonverbal intuition.

One of the issues I look forward to disentangling with Tyler has to do with the relationship between God and Creativity. For Whitehead, God is described as the primordial accident of Creativity, and thus as a creature rather than a Creator. I often refer to Whitehead’s God as the Relator rather than the Creator. Whitehead’s God is not the highest power, not omnipotent, in the traditional sense. In part as a response to the problem of evil that besets traditional theism, Whitehead denies that God is all-powerful or could ever contend tit for tat with finite physical forces. To the extent that God has any power, it is not of the coercive variety, but solely the power of persuasion or Love. God acts as an aesthetic lure goading each finite experient toward that which would be most beautiful given its local situation. Evil, then, is an inevitable side effect of the creative unrest disrupting every settled habit or established habitat. Even God cannot make reality stand still (which is why I often say it would be better to refer to it as “creality”).

I’ll wrap this post up with a few links that I hope help Tyler get a sense for where I am coming from. First, my talk at the McGilchrist “Metaphysics and the Matter With Things” conference I helped organize last Easter, which was titled “In Defense of Truth.” I think it speaks to the way I would also want to affirm a theory of “everyone,” over a theory of “everything,” to borrow Tyler’s terms. You’ll find the transcript of the video of the lecture at the first link below:

In Defense of Truth as Participation

Next is a short essay that introduces the idea of participatory truth as an alternative to the traditional representational conceptions of truth: From Truth as Correct Representation to Truth as Co-Creative Participation

What do you think?