I’ve just finished Ferguson’s book on James’ pluralist contribution to political theory. I can’t recommend it highly enough to those interested in the political implications of ontological pluralism. Ferguson contrasts James’ prescriptive pluralism to the far less radical liberal understanding of multiculturalism. For liberalism, pluralism is a problem to be overcome, whereas for James, pluralism is an end in itself. In the liberal model, individual and cultural differences must be identifiable within some homogeneous and abstract idea of the human. If a marginalized or oppressed group cannot make itself intelligible in relation to this idea, then it is left (or violently forced) outside the bounds of the properly political.

Ferguson also traces the devolution of James’ radical form of pluralism through the 20th century. What began in James as a call to affirm difference as essential for “experiential stimulation beyond the usual narrowness of human existence” gradually lost its force and was reduced to half-hearted calls for tolerance, and finally to a liberal apology for state power (deemed necessary to resolve people’s differences into some sort of national unity). Another major cause for the misapprehension and decline of James’ pluralism singled out by Ferguson is the

“shift in political science toward representing political actors as economic consumers. The increasing economism of political science has meant that many of the issues of interest to political philosophers–sovereignty, legitimacy, representation–have been recast as potential choices in a marketplace of ideologies, where voter/consumers are peddled competing brand names. When difference means little more than a ‘rational’ choice between commodities, pluralism ceases to challenge dominant formulations of political order. It instead becomes a way of organizing plurality into an ordered structure of classification, a ‘determinate system out of a multitude of conflicting individual wills which could be taken to be autonomous and underdetermined’” (27).

Ferguson also attempts to play down the ideological split between Continental and Anglo-American philosophies by delving into the close ties between Henri Bergson and James. There has never been a pure European philosophy, nor a pure American philosophy. Part of a pluralist ontology is acknowledging the tendency of identities to bleed together, to dwell within one another. Reality is messier than Reason’s airtight categories and fixed identifications, which is lucky, since otherwise there would be no room for us to breathe.

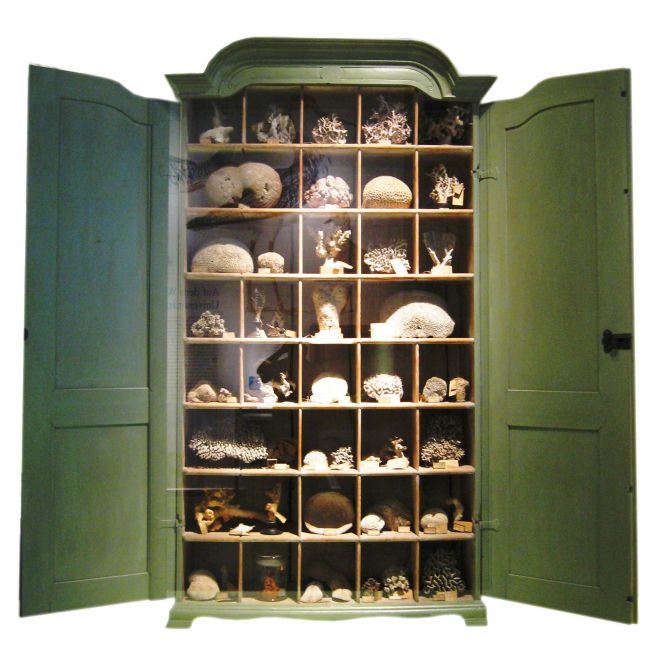

Ferguson ends his book with a fascinating discussion of James’ thing-orientation, which I found to be an insightful look at many of the issues more recently foregrounded by object-oriented philosophy. Ferguson gives a brief typography of thinghood as conceptions of it evolved from the medieval through the early and late modern eras. He dwells on examples like sixteenth century wunderkammern, or cabinets of wonder, Descartes wax candle, and Kant’s thing-in-itself.

What do you think?