Below is an audio version and edited transcript of my talk at Breaking Convention last week, hosted by the University of Exeter. Video should be available in the coming weeks.

Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes (Introduction)

It is my pleasure to introduce our next speaker, all the way from California: Dr. Matthew David Segall. Matt is an Associate Professor in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness Department at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. He is a transdisciplinary researcher who applies process-relational thought across the natural and social sciences, as well as to the study of consciousness. Check out his book Physics of the World-Soul: Whitehead’s Adventure in Cosmology. Matt and I along with a few colleagues are also launching the Mind-at-Large Project, which we can discuss in the Q&A. Please give him a warm welcome.

Matthew David Segall — “Psychedelic Realism”

Good afternoon, everyone. As Peter mentioned, I flew in from California last night and I am a bit jet-lagged—it is about 8 a.m. on California time. If anything I say sounds strange, perhaps one of these blotter-paper tabs from our name-tags is kicking in.

The title of my talk is “Psychedelic Realism.” I want to argue that the boundary-dissolving, world-enlivening states many of us have encountered under psychedelics reveal reality rather than distort it. There are good philosophical reasons—some of which we have already heard—to take these experiences seriously.

Philosophy’s Psychedelic Roots

What happens when you mix psychedelics and philosophy? Well, in fact, they have never really been separate. Classical Greek philosophy was born in a psychedelic milieu. Consider the Eleusinian Mysteries near Athens, a rite open to men, women, slaves, and foreigners alike. Initiates drank the kykeon, a potion scholars such as Hofmann and Wasson suspect contained ergot alkaloids—natural precursors of LSD. In that altered state they experienced the death-rebirth mystery associated with the Demeter/Persephone myth, signaling the immortality of the soul.

Here is Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting of Socrates calmly preparing to drink hemlock. In Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates is at this moment recorded as saying “Let’s get high, boys.” Just kidding: he actually declares in this dialogue that “philosophy is preparation for dying.”

There is a psychedelic reversal embedded in that claim. It echoes Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream: Are we a man dreaming he is a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he is a man? In short: How do we know we are really alive unless we have already died?

D. H. Lawrence catches the same insight when he writes that, as we approach death, we are “building the death-ship.” Philosophy, like psychedelia, has always been a vessel for crossing ontological thresholds.

Co-Evolution of Brains, Plants, and Fungi

Why do so many plants and fungi synthesize molecules that bind seamlessly to human neurotransmitter receptors? Because we co-evolved. The last common ancestor of all eukaryotes lived roughly a billion years ago, and plants, fungi, and insects have been co-evolving for about 400 million years.

Primary metabolites keep a plant alive; secondary metabolites (terpenes, alkaloids, tryptamines) act as ecological tuning-forks—chemical signals that coordinate relations within and across species. Psilocybin-producing mushrooms (Psilocybe spp.) evolved perhaps 20 million years ago; the cactus Lophophora williamsii (peyote) around 35 million.

As David O. Kennedy notes in Plants and the Human Brain, humans carry an elaborated version of the insect nervous system. The tryptophan-to-serotonin pathway is shared by insects and mammals alike, so fungal tryptamines “fit” our brains because our brains are part of the same ancient biochemical conversation. Consciousness is thus not trapped within the skull but ecologically extended. Every psychedelic session re-enacts hundreds of millions of years of symbiosis.

The Contemporary Research Renaissance

Aside from a brief blip in the mid-20th century, the academy all but ignored that conversation until Roland Griffiths’ 2006 Johns Hopkins study, “Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences,” reopened the field. Since then, scientists, philosophers, psychologists, and anthropologists have produced a torrent of data:

- Medical trials framing psychedelics as individualized treatments;

- Ritual-based, community-oriented healing in Indigenous contexts;

- Psychedelics as research instruments—think Bruce Damer’s visions of the origin of life or Merlin Sheldrake’s fungal insights.

Merlin jokes in his book about the questionnaire he received when he was coming down after an LSD trial, which asked him “on a scale of one to five, how would you rate your loss of your usual identity? How would you rate your experience of pure being?” This was difficult to quantify, as you can imagine.

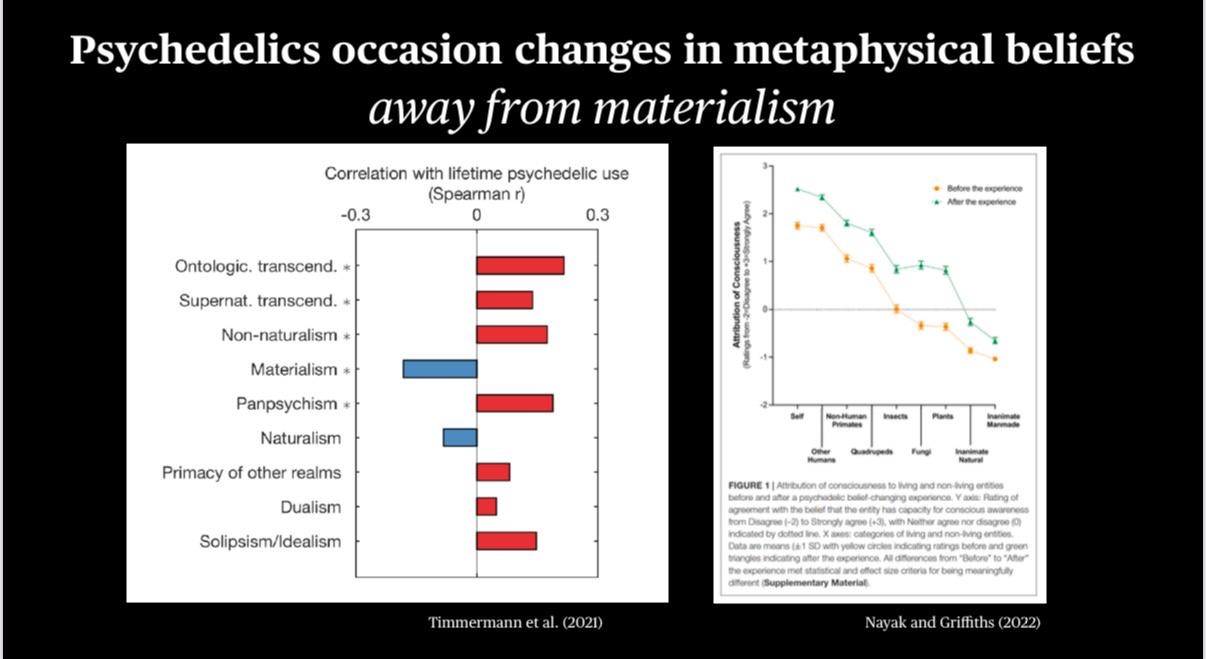

Chris Timmerman’s 2021 work shows that a single high-dose psilocybin session reliably shifts metaphysical belief away from materialism toward panpsychism or idealism. Participants also attribute consciousness to plants, insects, even stars more readily afterward. Griffiths’ follow-up studies reveal that two-thirds of self-identified atheists abandoned that label after either a spontaneous or psychedelic mystical experience.

Crucially, these belief changes correlate with lasting increases in well-being. Moving beyond reductive materialism seems good for mental health.

Are These Insights “Scientifically True”?

The journalist and researcher Michael Pollen—in a rather moving 2015 New Yorker article on end of life anxieties studies titled “The Trip Treatment”—asked whether psychedelic therapy was simply foisting a comforting delusion on the sick and dying.

He said it’s one thing if psychedelics create a feeling in a person that love is what really matters, because we can all easily to that. It doesn’t really step on any scientific toes. But what about when people have a psychedelic experience that convinces them to believe in an afterlife, or that leads them to reject scientific materialism?

Skeptics worry psychedelic experiences are foisting comforting delusions on vulnerable minds. Johns Hopkins’ David Yaden cautions that psychedelic “insights” might be false. Sanders and Zijlmans go further, warning that mysticism scales bias subjects toward “supernatural” interpretations and threaten the secular credibility of psychedelic science.

Yet both critiques take materialism as the “neutral ground” of scientific truth, even though materialism cannot explain why consciousness exists at all. If mind is an inexplicable side-effect of matter, perhaps the burden of proof rests with the materialist.

Now, to do justice to the concern here, there are cases where, in a psychotherapeutic context, somebody on psilocybin or MDMA has a repressed memory come up of childhood abuse: maybe they come to believe one of their parents or family members sexually abused them. In some cases it seems like that didn’t actually happen. But for the person who subjectively experienced it, it was very real. And so, we do need to come up with some new criteria and be epistemologically rigorous about how we make these distinctions. It’s not simply that what I’m trying to argue is that anything you experience on psychedelics is true.

Four Metaphysical Options

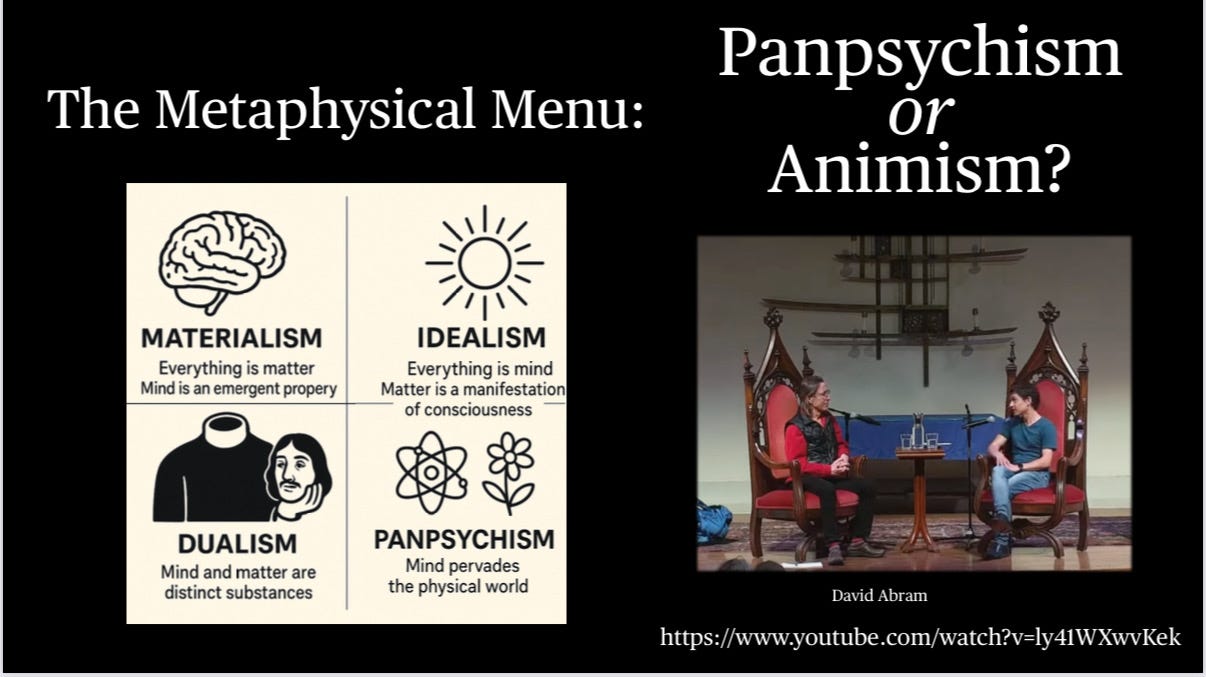

We face four broad positions on mind’s place in the universe:

- Materialism – only matter is real; mind is a late-emerging epiphenomenon.

- Dualism – mind and matter are separate substances.

- Idealism – mind is fundamental; matter is a manifestation of consciousness.

- Panpsychism / Animism – mind pervades the physical world at every scale.

Animism, as David Abram emphasizes, is not mere theory but an embodied stance that hears rivers, mountains, and winds as living presences. Panpsychism is the analytical philosopher’s way of articulating that felt animacy. Both register a cosmos of inwardness rather than inert stuff.

From Representation to Participation

Alfred North Whitehead observed that modern epistemological problems are disguised ontological problems. If you assume a materialist ontology, you are forced into a representational theory of perception: the mind never meets reality, it only constructs neural models inside the skull.

Whitehead’s alternative is rooted in his novel theory of “prehension”: when an organism feels the world, it is the world itself flowing into experience. Romantic poets likened the mind to an aeolian harp—like sound arising when the wind (world-spirit) vibrates its strings. Perception is participation.

Truth, then, is not passive correspondence but risky relationship. Psychedelics dramatize that risk: they alter the knower herself, not merely her ideas about the world. Knowing truly becomes a moral-spiritual practice that invites transformation.

Q & A

Question 1 (audience):

Psychedelic experiences sometimes seem to reveal “real reality,” but at other times they mislead or even harm people. If we set aside the old correspondence theory of truth, how do we decide which visions to trust? Could a pragmatic test—“if it heals, it’s true”—suffice, even though healing experiences might still be factually wrong?

Matt:

William James advised us to focus on the fruits of experience, not the roots. We can debate metaphysics forever, but the practical measure is whether an experience deepens relationship, reduces narcissistic projection, and enhances the flourishing of life. If we want a fully participatory theory of truth, we still have to ask the perennial metaphysical questions—“Who am I?” and “What is this?”—yet in service of healing it can be wiser to judge by the fruits. Pragmatism keeps us oriented to value: does the vision regenerate life and strengthen our relational web? If so, that is strong evidence in its favor.

Question 2 (Sue Blackmore):

Predictive-processing models say the brain is constantly generating representations or “controlled hallucinations” to guess the world. Andy Clark argues from this point of view. Doesn’t that clash with your participatory view, which downplays representation?

Matt:

There is some level at which representation occurs, particularly when we are thinking linguistically. But we err when we treat linguistic models as a picture of how our perception works biologically. I value Andy Clark’s “extended mind” idea, yet when predictive processing is framed as if consciousness is locked inside the skull, we become neuro-centric again. Organism and environment form a single recursive loop: every action reshapes the world, and the changed world reshapes the organism. Calling this loop a perpetual hallucination is just an unfortunate metaphor. Better to say we engage actively with a world that is co-evolving with us—no gap, no inner cinema—just participatory feedback. The brain can be modeled as a Bayesian calculator, but I doubt it really is one.

Question 3 (audience):

Do you treat synthetic compounds like LSD or MDMA differently from plant medicines? Are artificial molecules “alive” in any meaningful sense?

Matt:

From a panpsychist angle every molecule vibrates with its own kind of interiority. Nature does not draw a bright line between “natural” and “synthetic”; our chemists are just exploring new regions of the same molecular possibility-space. Each compound has its own integrity and potential form of sentience. Some may interact with us beneficially, others harmfully, and much depends on set and setting. Rather than policing an artificial natural-versus-synthetic boundary, we should attend carefully to what each molecule discloses in practice and learn from the results.

What do you think?