Yesterday in my history of Western philosophy course, where my students are reading Richard Tarnas’ Passion of the Western Mind (1991), I lectured on a couple of seventeenth century philosophers in an attempt to catch the nature of the shift that historians call “the Enlightenment.” I then connect their innovations to a couple of nineteenth and twentieth century philosophers to gesture toward an altered form of modern consciousness, or the modernity that could have been (or could still be). What follows is an expansion based on the transcript of my lecture.

In the background of this lecture is the long arc from the intense religiosity of the medieval world and the last explosions of fervor in the Reformation and Counter-Reformation into a period of relatively rapid secularization. The irony is that many of the motivating ideas originally given a religious interpretation now become engines of disenchantment. To see what this means for the evolution of consciousness, I trace a lineage of thought from Descartes through Spinoza and Leibniz, and then forward to Schelling and Whitehead.

Descartes

The ancient Greek mind could still feel thought streaming in from the cosmos. The world presented an intelligible order that philosophers could directly perceive. By the time we reach Descartes, roughly two millennia later, a remarkable transformation has occurred. Thought is now understood as produced by the self-conscious ego, by the activity of our own mind. Ideas are no longer eternal forms irradiating the cosmic display but conceptual constructs we abstract from and use to label to the world.

Descartes suspends inherited authorities—ecclesial and Aristotelian—and submits even mathematics to a radical method of doubt. At bedrock he discovers the indubitable reality of his own thinking. From there, correlate to his own experience of finitude he encounters the “infinite idea” of God and reconstructs the reality of the world under the assurance that a good God would not deceive us. In the same stroke, his new science scrubs nature clean of purposes: nature becomes a machine. Atheism becomes a live option, and God shifts from an obvious given to an unnecessary hypothesis; yet Descartes’s confidence in reason still borrows against a divine credit line.

Spinoza

Spinoza radicalizes the modern trajectory by monistically dissolving the dualistic split that generated the interaction problem. There are not two substances, mind and matter, awkwardly bridged by some causal gizmo in the pineal gland. There is one infinite substance—God or Nature—with infinitely many attributes, of which we grasp thought and extension. Everything that exists—ideas, emotions, minerals, plants, animals—is a mode, a finite expression of that single substance. Analyze any mode and you find only relations leading you back to the one substance again. Mind and body are thus two aspects of one and the same substantial activity. The old puzzle “how do ideas move limbs?” is incorrectly posed: the mental and the bodily are parallel expressions of an identical order. There is no cross-attribute causation to explain.

Within this single order each finite being or mode strives to persevere. This is there conatus. This striving is affectively toned: joy marks an increase in a thing’s power of acting; sadness marks a decrease. Spinoza is not anti-emotional. He replaces moralism with an ethology of affects. The task is to learn what increases our capacity to act and to compose empowering relations, what Deleuze glosses with the provocation “what can a body do?” Freedom, accordingly, is not exemption from necessity but an intelligent love of it, the serenity that comes with adequate ideas of ourselves and the whole. In a strict sense neither we nor God “choose” otherwise than what follows from the nature of things. But in the ethical sense that matters, freedom grows with comprehension, as reactive passions are transformed into active understanding.

Evil has no independent standing. It names our partial grasp of the necessary whole, the mismatch between inadequate ideas and the reality they imperfectly register. As understanding becomes more adequate, perception is healed. This is why Deleuze can call Spinoza the “Christ of philosophers”: because he heals vision—remove the log from your eye and the world discloses itself as it is, an immanent order to be understood and loved. Reason here is not a cold calculator but a discipline of humility, goodness, and compassion. To live by reason is to compose joyful affects, to repay hatred and contempt with nobler responses, and to cultivate common notions through which our powers converge rather than collide. In this way the modern piety of reason becomes an agapic practice: by knowing ourselves as modes of God or Nature, we learn to love our fate, and in that love taste the only freedom Spinoza recognizes.

Leibniz

Leibniz offers another, pluralistic path beyond dualism without dissolving difference. The world is composed of simple, private, perceptive centers—monads—that have no windows and no causal commerce with one another. Their inner unfoldings run in perfect mutual coordination by virtue of a pre-established harmony. No causal bridge is required between inner ideas and outer motions; their alignment is given with creation. In this way Leibniz learns from Spinoza how to overcome Cartesian dualism, but he does so pluralistically: mind and body do not interact; they run together in a perfectly coordinated parallelism established by God at the beginning of time, much like two synchronized clocks whose gearwork keeps the same time without the clocks ever touching.

Monads have no spatial extension and cannot be divided. Each is a center of perception and appetition, a little mind with its own unique perspective and an internal drive to unfold itself. In the Monadology he insists that nothing so small or so confused fails to express the whole universe. Here the contrast with Spinoza’s modes is decisive: for Spinoza, modes dissolve into their relations and lead us back to a single infinite substance; for Leibniz, monads remain fully self-enclosed, preserving individuality and (he hopes) a stronger footing for freedom. He wants to be modern and ancient at once: to keep faith with mechanical lawfulness while retaining the final causes in nature that Plato and Aristotle would recognize. Hence the dialectics he’s always trying to hold together between one and many, freedom and order, divine will and divine understanding.

He fortifies the whole picture with the principle of sufficient reason: nothing happens without a reason; every fact is, in principle, intelligible. Where the empiricists leave room for brute contingency, Leibniz insists on intelligibility through and through. These commitments culminate in a much-mocked but philosophically serious theodicy. The thesis that we inhabit the best of all possible worlds is not naïve optimism. Read more sympathetically, it is the claim that optimization always occurs under constraints. To actualize a coherent, law-governed world while aiming at maximal goodness and beauty requires trade-offs. One cannot have a world that is locally “best” at every point and still retain the stable order that makes a world a world. In the Monadology he puts the point aesthetically: God chooses a world “simplest in hypotheses” and “richest in phenomena.” Perfection is harmony, not a static polish but a dynamic coordination of many independent voices in a higher unity. No accident, then, that Leibniz says music is the pleasure the soul takes in counting without knowing that it counts.

Leibniz’s metaphysical taste for reasons shows up in his natural philosophy. He presses Newton on action at a distance: if space is a void, through what medium does gravity act? Descartes had already filled the cosmos with vortices to avoid occult forces in empty space. Others, like Margaret Cavendish, leaned toward plenist and even vital accounts of matter. Leibniz’s complaint targets precisely the spot where mystery threatens to masquerade as explanation: he wants lawful mediation, not hidden miracles. In the Leibniz–Clarke correspondence he accuses the Newtonians of turning God into a celestial tinkerer who must periodically adjust the machine. Is God really just a poor clockmaker? Against Newton’s absolute space and time, Leibniz defends a relational view and insists that gravitational phenomena admit of intelligible reasons rather than action through a vacuum.

Leibniz was a courtier and an ecumenically minded Christian who wanted to reunify the churches; he was also a jurist, engineer, mathematician, and tireless organizer, contributing to legal codifications in the courts where he served and dreaming of a universal encyclopedia. The philosophes admired him even when they disagreed. Denis Diderot, for example, quipped that:

“When one compares the talents one has with those of a Leibniz, one is tempted to throw away one’s books and go die quietly in the dark of some forgotten corner.” (Oeuvres complètes, vol. 7, p. 678).

Yet patrons often found him exasperating: he promised genealogies, mining schemes, administrative reforms, then disappeared into the details trying to perfect a never completed whole. He spent decades on the House of Brunswick genealogy. Despite his travels and vast correspondence (over a hundred thousand pages), he died in obscurity. Legend has it only his secretary attended his funeral. The final years were clouded by a priority dispute with the Newtonians over the invention of calculus. The fairest verdict is that Newton and Leibniz discovered it independently: Leibniz published first, while Newton had it in notebooks—proof that the time was ripe for a new way to calculate motion and domesticate infinity.

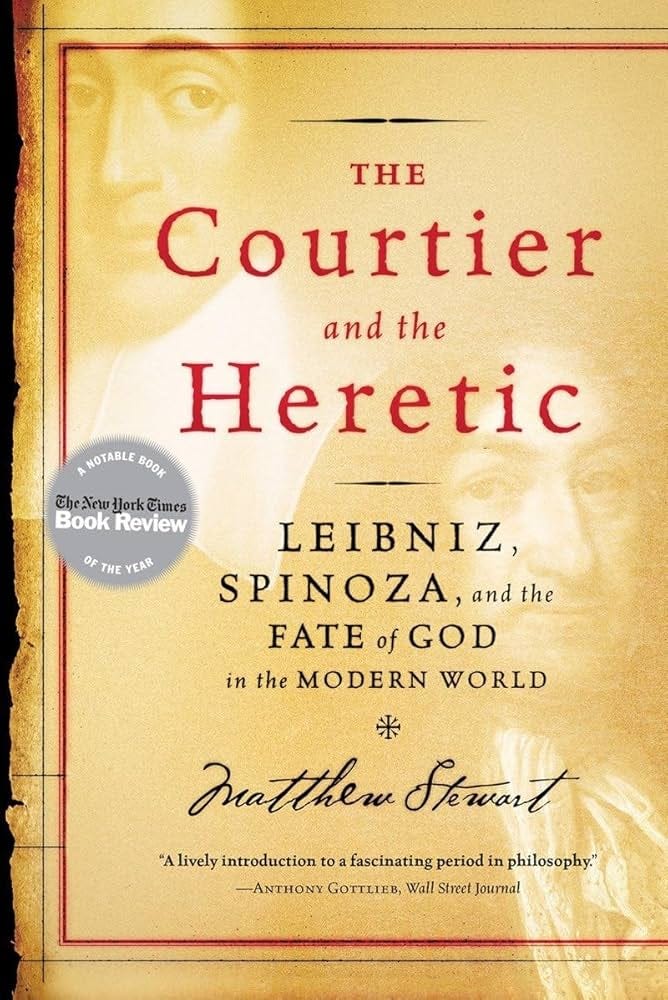

Leibniz’s November 1676 meeting with Spinoza belongs in the story. Because of Spinoza’s philosophical infamy, Leibniz kept the visit quiet. As a courtier he could ill afford the scandal. In letters, he sometimes boasted of the meeting and at other times denied it, behavior that fuels Matthew Stewart’s harsh portrait of Leibniz as a pathological liar (more on Stewart’s book below). A kinder reading is that he was a deft conversationalist practicing skillful means, tailoring his presentation to his audience. Either way, the meeting sharpened the tensions Leibniz was trying to hold: to resist Spinoza’s determinism while preserving the beauty of a lawful cosmos, to defend freedom without surrendering reason, to write a polyphonic metaphysics in which many voices sing as one.

Matthew Stewart’s The Courtier and the Heretic: Leibniz, Spinoza, and the Fate of God in the Modern World (2006) combs the archives and stitches together an entertaining account of Spinoza’s influence on Leibniz, from hearsay through a brief correspondence to their quiet meeting in The Hague in 1676.

Stewart’s presentation of both ideas and character tilts sharply in Spinoza’s favor. Spinoza becomes the anti-mystical rational hero of modern liberalism; Leibniz becomes a socially needy medieval throwback and a pathological dissembler who cribbed his best ideas. Stewart psychoanalyzes Leibniz’s philosophy through the loss of his father at age six. This is easy to do partly because Leibniz is so well-documented—over 150,000 pages of letters and papers—while Spinoza, excommunicated at twenty-four, receded into a mostly shrouded life. Spinoza’s legend grows; Leibniz’s foibles are on display. Stewart laments a “reactive” modernity descending from Leibniz and claims it has become dominant, listing Kant, Hegel, Bergson, and Heidegger as heirs who refuse to face the purposeless universe revealed by science and the bloody course of political history. Contra Leibniz, he suggests, this is plainly not the best of all possible worlds.

My own view is that each of these seventeenth-century thinkers wrestled with the same modern predicament: how to reconcile a mechanizing science with ineradicable questions of meaning, purpose, and value. And on the philosophical side, there is something undeniably profound in both Spinoza’s monism and Leibniz’s monadology.

Schelling

My own philosophical heroes, Schelling and Whitehead, both learned a great deal from Spinoza and Leibniz. Schelling argued his entire life on behalf of freedom—for humanity, for nature, and for God—yet he lavishes praise on Spinoza’s system for its “peacefulness and calm” and insists that no one can hope to reach the whole truth without once “losing themselves in the abyss of Spinozism.” But for Schelling, Spinoza is a springboard, not a resting place. Spinoza’s God, identical with nature, becomes for him a dead substance incapable of going out of itself to create. Spinoza’s closed system leaves us no satisfying way to understand the transition to the appearance of finite things, only an explanatory regress into infinity.

Schelling admires Leibniz’s monadology but ultimately views it as “a stunted Spinozism” that inherits necessity under a new guise. Still, Schelling values Leibniz’s sense of nature’s stages of awakening to spirit: sleeping mineral monads, dreaming plant monads, waking animal monads, and self-aware rational monads. He poetically intensifies Leibniz’s earlier attempt to think God’s grounding decision prior to the existence of the world into an experiment in temporaling eternity, reaching for a past that was never present in which God goes out of Godself in the creation of the world. Schelling’s unfinished text Ages of the World labors to articulate how genuine freedom—divine and human—requires a dipolarity in God, a succession of potencies, so that eternal necessity and free deed can meet without collapsing in a solitary simultaneity.

In the end Schelling faults both Spinoza and Leibniz for denying real life and freedom to God. Spinoza does so forthrightly: God’s “freedom” is simply to be what God is—substance, simple, unified, unchanging being. Leibniz attempts to retain divine freedom by distinguishing will from understanding, but by insisting that God must choose the best, he reduces freedom to a logical device—the last resort of rationalism—and quietly converges with Spinoza’s necessity. Stewart’s endnote is apt here: before he knew Spinoza, Leibniz was already against Spinoza; but he also had a Spinozistic side. The encounter forced him to wrestle with the dangerous Spinozist within.

Whitehead

According to Schelling, neither Leibniz nor Spinoza can finally account for the transition from the infinity of their respective absolutes to the finitude of actual experience. Pure reason alone offers no path from the ideal to real life. Whitehead begins Process and Reality by recommending that speculative philosophy reimagine itself as an experiment on experience. As Whitehead puts it: “start on the ground of particular observation, take a flight in the thin air of imaginative generalization, and land again for renewed observation, sharpened by rational interpretation.”

Whitehead certainly owes much to both predecessors, but rather than just resemble he re-assembles their insights and, in doing so, alters their meaning. Leibniz’s substantial monads become process-relational occasions, not windowless but almost all window. Spinoza’s infinite substance becomes Creativity: neither finally one nor many, but the transitional intra-relationship whereby the many become one and are increased by one, again and again to the crack of doom. God is not an exception to the metaphysical principles applying to all finite entities but the chief exemplification of those principles. Whitehead’s God is dipolar like Schelling’s, with a primordial envisagement of possibilities and a consequent embrace of whatever beauty can be harvested. Without divine Eros, nothing could become; Being would remain unmanifest, unable to ex-ist, unable to stand out and so hidden even from Itself.

Modernity tempts either evacuation (no God) or imposition (deus ex machina), as if the only available choices are godless evolution or young earth creationism. Schelling and Whitehead model an alter-modern third way: an incarnational metaphysics in which God names the living depth of possibility and the lure of value, not a cosmic engineer lowering skyhooks from outside and above the frame of a clockwork world. Their philosophies are fully secular in the sense that they are concerned with the effects of thinking on this world. They approach metaphysics and theology as a disciplined study of the evolving divine ground of nature, not as an escape hatch from it.

…

Spinoza teaches the serenity of intelligibility; Leibniz, the audacity of reason in a lawful cosmos; Schelling, the drama of freedom in nature and in God; Whitehead, the empirical discipline and speculative grammar needed to say how the many become one without betraying experience. Rather than anti-modern consolations, these moves amount to an alter-modern wager: that our consciousness is truer to itself when it admits knowing is a lover’s work. Philosophy, in its eros for reality, can neither deny suffering nor abandon intelligibility. If the Enlightenment dimmed the stars so we could count them, Schelling and Whitehead invite us to let our eyes adjust. It may turn out that love, not cynicism, is the more objective scientific instrument. Clarifying our lenses may take a lot of grinding but it need not be joyless.

Leave a reply to dltooley Cancel reply