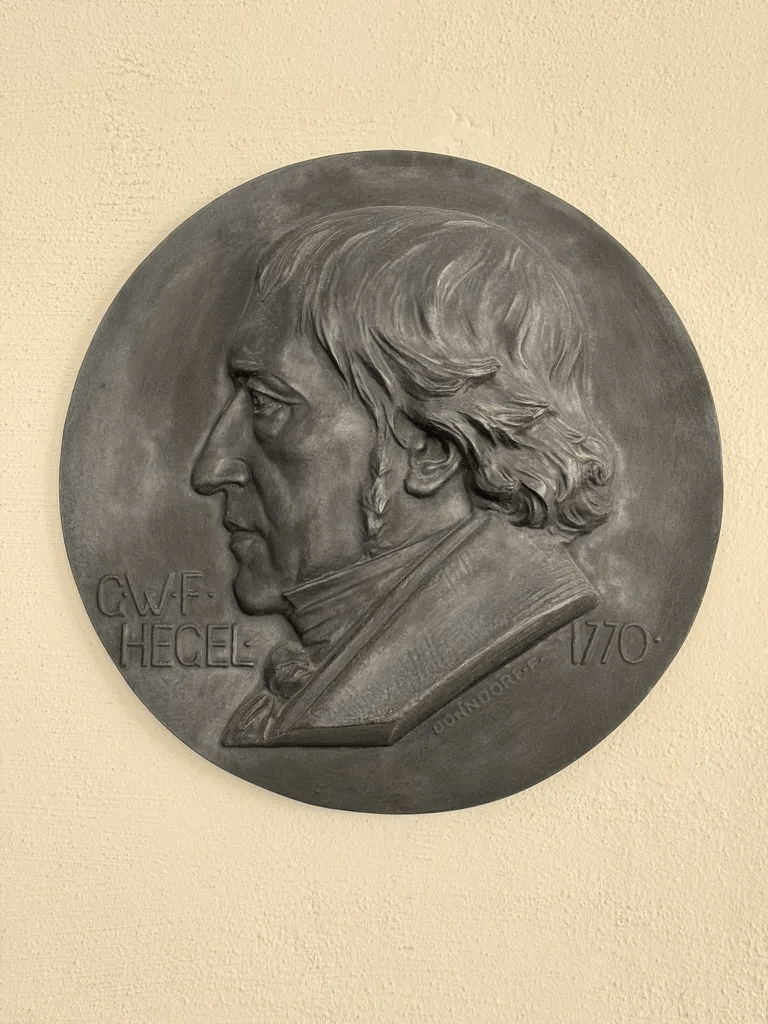

A slightly revised transcript of my introductory lecture from a course on Hegel’s Absolute Idealism.

I just want to begin by noting that Hegel’s time was a time of revolution in Europe. The French Revolution, in many ways, shaped the political categories that all the modern liberal democracies have been assuming for the last couple of centuries. And here we are studying Hegel in a time when we are once again, I would say, on the verge of some kind of revolution—when perhaps those categories that have held sway for a few centuries are being dialectically overcome to bring forth something new that we’re struggling to see.

So studying Hegel now is of particular relevance. Hegel finishes writing the Phenomenology of Spirit as Napoleon invades Jena, where he had been living. And so, while these ideas might seem very abstract at times, Hegel was driven to think in the way that he was because of the historical moment that he was living through.

Let me just briefly read from the preface of the Phenomenology of Spirit, where he speaks to this. He says:

“It is not difficult to see that ours is a birth-time, and a period of transition to a new era. Spirit, or Geist, has broken with the world it has hitherto inhabited and imagined, and is of a mind to submerge it in the past, and in the labor of its own transformation. Spirit is indeed never at rest, but always engaged and moving forward. The gradual crumbling that left unaltered the face of the whole is cut short by a sunburst, which, in one flash, illuminates the features of the new world.”

So we’re searching, as we study Hegel this semester, for that sunburst, I would say. And whether or not it illuminates a path forward—we’ll see.

Let’s transition now, and I’ll offer a very brief sketch of the history of western philosophy from Parmenides to Hegel. These are just signposts, highlighting the ways in which that whole history, from Hegel’s perspective, can be understood as a kind of tragic-comic drama where this basic tension between thought and being is trying to work itself out in a process of progressive self-clarification and self-realization.

Hegel’s perspective on that history is not that he’s just offering one more theory that would be within the drama. He wants to depict this drama in a participatory way—not simply from the outside, but also not just from within it. He’s very much trying to be inside of it and to participate in all of the various steps and stages and shapes that consciousness moves through in the course of this history, but in a way that sees into and through that variety to the eternal, ever-growing System it expresses. He’s not just offering yet another theory but a kind of meta-theory.

He wants to show the internal logic and necessity unfolding through the drama in the form of a single Idea, which, paradoxically, he will later come to identify with Freedom. When Hegel talks about the Idea, it’s a bit like Heraclitus’ Logos: it’s a principle of intelligibility, but it can’t be captured and frozen and reduced to a formula. It’s a dialectical process that’s continually overcoming itself. He’s trying to initiate us into that process so that we can then look again at this history and see how what appear to be just a bunch of warring opinions are actually one Idea trying to work itself out.

Someone mentioned that Hegel seems like a “walking contradiction,” and I love that phrase, because usually we think of contradiction as like hitting a brick wall—it stops us in our tracks. But Hegel walks through walls. Contradiction becomes the engine of his philosophy. Rather than restraining us, it’s more like a slingshot: it propels us. So “walking contradiction” is a great description of Hegel.

So let’s take a magical mystery tour through the history of philosophy. But one more thing about Hegel’s method to keep in mind before we go: he’ll distinguish, as we’ll see later on, between the understanding and reason. For Hegel, the understanding is this way of engaging with concepts that always inevitably ends up discovering their contradictions. The understanding is obsessed with divisions and static categories. Reason, for Hegel, is more organic, more fluid. It is able, through what Hegel calls speculation, to see its way through what, for the understanding, remains simple oppositions. Reason allows us to see how there’s a deeper identity between identity and difference, as Hegel would put it. It dissolves differences without simply erasing them. That’s very important. So just keep that in mind when we look at the history of philosophy from a Hegelian point of view. We’re not just opposing irreconcilable points of view. We’re trying to see the way in which those very oppositions generate a higher point of view which would include them.

As Hegel does in his history of philosophy, we’ll begin with the ancient Greeks and the pre-Socratic thinkers. Of course, the Greeks had their influences (which Hegel acknowledges, even if he reserves “philosophy”—a Greek word, after all—for Greece). Plato himself talks about the influence of Egypt. There’s a lot of speculation about influences coming from India, influencing Pythagoras, and through him Plato and Greek philosophy. Of course, after Alexander the Great’s conquest, moving so far east, there was a huge influx of Asian culture and religion back into Greece. East met West a long time ago; East met West met South a long time ago. So to begin with ancient Greece is not to say that this philosophy just emerged out of nothing. There were many influences already converging in ancient Greece.

On the other hand, there is what Karl Jaspers’ called an axial breakthrough that occurs in ancient Greece, where a new form of theoretical, reflective consciousness is coming into its own. This happened on other continents around this time, too, but in distinct ways. It’s in ancient Greece that the rupture between myth and theory, or between thought and being, occurs that generates all of these problems in the history of philosophy. There was a form of what anthropologists would call participation mystique that was typical of how human beings prior to this axial rupture tended to relate to the world, where we were more immersed in the rhythms of nature. This eruption of reflective or theoretic consciousness started to make human beings feel increasingly alienated from nature. Existence all the sudden became a problem for itself.

So we can begin with Parmenides, who had this intuition that—well, you could put it as simply as: being is. Whatever we can think must already be, in some sense, part of being—internal to being. For Parmenides, what’s most real—whatever is real—must be intelligible, because thought and being are not separate from each other. What can be thought and what can be are identical, in other words. So Parmenides would say, “Non-being is not.” That sounds like a tautology, but what he’s saying is that this idea of nothing can’t actually exist or even be thought. Anything that can be thought must exist.

This intuition that Parmenides had generates logic; it generates the idea of non-contradiction, which is essential for logical thought, even though Hegel will attempt to dialectically overcome that, as we’ll see. But it generates a whole bunch of paradoxes. If being is, and thought is identical to being, as Parmenides intuited, then the idea of change or motion becomes very difficult to understand intellectually. It leads to Zeno’s problem about motion, where the example is: if you fire an arrow at a target, the intellect will want to understand that in a geometrical way. You can imagine or rationalize this movement of the arrow to the target by saying, well, the distance from the arrow to the target is a line that first needs to be halved. And then halved again, and then halved again. In terms of the intellect’s attempt to calculate that motion, the halving can continue infinitely, and it’s as if the arrow could never reach the target, because the intellect can only think in these static instances. Now obviously the arrow does reach the target. Zeno’s arrow becomes this problem that philosophers for millennia try to work through. It suggests that, as Henri Bergson would say in the 20th century, the intellect just can’t understand real movement. There’s something that exceeds the intellect’s ability to understand—maybe not reason’s ability, but the intellect, as the understanding, seems incapable of understanding becoming.

Now after Parmenides there’s Heraclitus, who in a sense is the inversion of what Parmenides is saying. Heraclitus wants to say that becoming is real, change is real. Reality is not a static substance; it’s a kind of self-transforming process. The order, or the Logos, of this process is impossible to understand unless you can confront contradiction with a different organ—with reason, as Hegel would put it. Rather than saying that non-being is not, as Parmenides would, Heraclitus would say that non-being, or nothing, is inseparable from being. You can see already, if you’ve read Hegel’s Logic, that this is how Hegel begins and sets thinking into motion by dialectically sublating the difference between being and non-being, which generates becoming. Heraclitus is a key influence on Hegel.

So rather than seeing becoming and change as exceeding thought, or an expression of the failure of thought, a contradiction that stops thinking in its tracks, Heraclitus allows us to see becoming as the very life of thought. It’s the engine of thinking. Thought—or again Logos, as Heraclitus refers to it—is always manifesting itself through the tension of opposites. Logos can be understood as the transforming agent that allows for the oppositions of the understanding to be overcome.

This tension between Parmenides and Heraclitus is perennial. It frames the whole rest of the tradition of Western philosophy, where there’s an attempt to deal with this apparent divergence between intelligible unity on the one hand and creative movement on the other. You could say it’s the tension between the need for rational system on one hand and the desire for living freedom on the other. Hegel’s claim is that we can overcome this difference between system and life, without collapsing into irrationality, but only by grasping this whole history, including all of its internal contradictions, as Absolute Spirit trying to come to know itself.

After Parmenides and Heraclitus is Plato and Aristotle. They intensify this dialectic. Plato tries to preserve intelligibility, even though he doesn’t really develop a system. He writes dialogues and explores different ideas, but he tries to preserve rational intelligibility with his theory of forms—eternal forms. There’s a cost there, though, which is that the sensory world of our everyday experience starts to seem like a kind of illusion, an appearance that needs to be overcome. There’s a risk in this Platonic emphasis on the forms—the eternal forms as what’s true and real—that our sensory experience and our embodied lives get dismissed as mere appearances.

There’s a way in which Plato’s dialogue Timaeus, his cosmological dialogue, is an attempt to synthesize or integrate the Parmenidean point of view with the Heraclitean point of view. In that dialogue, in trying to understand the origins of the universe, Plato has to confront the limitations of intelligibility: the world as it appears to us and as we reflect upon it displays a certain givenness, what he would call, in Greek, anankē. It’s usually translated as “necessity,” which is not a perfect translation because anankēin Greek also means something like “arbitrary.” For Plato, the intellect—the Nous—is constrained by the nature of becoming.

In the Timaeus he frames this in terms of Nous meeting and mingling with, and trying to reconcile itself with, the Khōra, or what he calls the Receptacle. The Khōra is like the form of formlessness: that which receives all form and allows form to manifest. You see, in the Timaeus, Plato struggling with the way in which the universe is intelligible and yet also that intelligibility has certain limits—which is why he says in this dialogue that he can only tell a “likely story.” Plato is almost always ending his dialogues with a myth that attempts, not to rationally solve the problems that he’s laid out, but to show in a more imagistic way how the contradictions can be overcome. But Plato’s not doing it logically; he’s still relying on myth. So you can see: while theoretic consciousness is struggling to burst through in Plato’s writing, it’s still what Eric Voegelin would call “mythospeculation,” which relies upon myth and symbol to carry us further than theoretical or rational reflection can.

Aristotle is the first Neoplatonist: inheriting Plato’s insights, but then trying to immanentize form, you could say. So rather than form being eternal, Aristotle sees form at work in the sensory world, in the empirical world. He gives philosophy its first systematic vocabulary. All of the categories that science still uses to study the world are inherited from Aristotle—physics, biology, psychology, and so on. For Aristotle, change and becoming are not simply a kind of unintelligible chaos. He understands the world of becoming as a form of teleological growth. For Aristotle, form isn’t just about eternal perfect ideas; form is what’s working itself out in the development, say, from an acorn into an oak. So he’s immanentizing what for Plato was transcendent, and he’s putting it into motion, but motion in a teleological way. It’s not yet the sort of open-ended creative evolution we would see after Darwin and his understanding of biological evolution, which almost tips over what for Aristotle remained a vertical great chain of being—from mineral to plant to animal to the human, to the divine, which was just thought thinking itself. It’s as though modern evolutionary theory tips Aristotle over to make what was vertical horizontal. And what was, for Aristotle, “an unmoved mover” at the crown of the cosmos becomes for Darwin something more like an unorganized reduction base of “matter moving itself.”

So you can see how philosophy already, with Plato and Aristotle, is teetering from side to side between rationalism and empiricism. The issue for Plato and Aristotle was not yet one of subjectivity versus objectivity; I think that’s more of a modern intensification of what for the ancient Greeks was still a more impersonal relationship between thought and being. The difference is that for the Greeks, knowledge for both Aristotle and Plato was something objective. The forms, for both Plato and Aristotle, existed independently of individual minds. Form wasn’t yet something that, as it would become in modern philosophy, resided within individual minds. It was in the world.

We’ll see, when we get to the nominalists in a moment, how dramatically that shifts the stakes. But before I get to that, I need to mention the Christ event. Hegel was capable of seeing how within religion—and for him, Christianity—there is a symbolic expression, or even a revelation, of the Idea that philosophy works out conceptually. He related to the Christian mystery and the Christ event as another avenue to realizing the Idea.

From Hegel’s point of view, this Christ event is this moment where the eternal and the historical are integrated. Through the incarnation, the suffering, and the death and resurrection of Christ, Hegel sees a dialectical process working itself out. As a result of this Christ event, for Hegel, you can’t understand the Idea as something above history. It’s entered into history, and it’s working itself out through history. The difference between history and myth, in a sense, is canceled in the Christ event, again as Hegel understands it. Or you could say the difference between a historical fact and a symbol is overcome.

It’s similar to what I was saying earlier about the way Hegel’s not just offering another theory to find its place within this drama of the history of philosophy, but trying to understand that whole drama in a new way. The Christ event—you can understand it as if the creator entered into the story to become a character in it. That would be from the divine perspective. From the human perspective, it’s as if we—who had been characters for whom the story seemed already written—are now called to become co-authors or co-creators within that story. This is how Hegel is relating to the Christ event.

I want to mention Plotinus next as someone who is refining this process of mediation between the eternal and our embodied existence. Plotinus was already having to engage with Christianity and engage with Gnostic Christians. So there’s a development in philosophy here where there’s a real effort to seek out mediation between eternity and embodied existence. For Plotinus, you have this emanational scheme where the manyness of the embodied world is understood as an emanation from the One. There’s also a return, or an integrative movement, that Plotinus writes about: we issue from the One, and through contemplation of the One, return to it. This gives the first philosophical articulation of the movement of the Idea through a process of initial estrangement and then the possibility of reunion. I think Plotinus is an early attempt at something similar to what Hegel proposes.

Now, nominalism, as I mentioned, is this moment when the forms or the universals started to lose the ontological weight that they had in the Platonic and Aristotelian traditions. Ideas, forms, universals are increasingly understood as mere names—just linguistic constructs. They reside within the human mind. This shifts the burden of intelligibility to the human subject.

Initially, the nominalists were theologians who were driven to challenge this old Platonic and Aristotelian idea of universals in order to preserve the power of God. They wanted to preserve divine freedom to create whatever sort of order—logical and cosmological order—that God wanted, because God’s free and God’s not subject to even the rules of logic. So what was initially this nominalist move to preserve the power of God, and to make sure that this Christian theological understanding of divine omnipotence wasn’t challenged by the Greek understanding of logical order—that is, for Plato, God is good because it’s Good; the Good isn’t good because God says so, and it’s a matter of the priority there—what begins for the nominalists as a theological argument to preserve divine omnipotence becomes, after the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment, much more understood as being about human freedom, and human power.

This is where, through the modern period, knowledge becomes increasingly something understood to be subjective, not objective as it was for the ancient Greeks—although there were skeptics already in ancient Greece for whom some of these modern ideas were prefigured. It’s amazing when you study ancient Greek philosophy: there’s far more going on than just Aristotle and Plato. Almost the seed form of every major school of thought that we recognize in the 20th and 21st centuries was already present in the Hellenistic world.

I want to mention Joachim de Fiore, who’s a 12th–13th century theologian who developed this idea of developmental revelation through three ages: the age of the Father, which he recognized as the Old Testament period; the age of the Son, which he thought was the age of the Church, the Catholic Church; and then the age of the Spirit, where Joachim thought the church wouldn’t be necessary anymore because individuals would become awakened to the presence of love within themselves, and they wouldn’t need a hierarchical structure. Obviously, the Church didn’t like that very much. But I think this depiction of history, this tripartite vision, is very similar to what Hegel will end up doing, where there are these epochs of qualitative transformation and shapes of consciousness where humanity’s relationship to the divine is deepened. It’s an early precursor to what Hegel does.

The next major signpost here would be Anselm’s ontological argument for the existence of God, which is this attempt to reunite thought and being through the idea of necessity. Anselm’s ontological argument is an attempt to say: we have this idea of perfection, and Anselm thought that a truly perfect idea isn’t just a concept anymore. The highest idea that we can imagine, for Anselm, must necessarily exist. Of course the highest idea would be God. God is that for whom existence is necessary.

There’s a way in which what ends up being intuited here—and this is part of what the Christ event and the mystery of the incarnation is compelling thought to think—is the way in which our own thinking activity, as individual human beings, is in some sense participating in the actuality of the divine. It’s this argument that reason is in some sense a divine gift that allows us to understand what is actually the case: that there’s an internal relationship between thought and being. Being is not simply given to thought from the outside or on accident.

Now there’s the Protestant Reformation, which brings an interiorizing of how human beings come to justify their own thinking. Martin Luther was obviously trying to remain true to scripture in resisting some of the excesses of the Catholic Church. However, he unleashed this form of subjective freedom and intensification of an individual’s sense of what can count as justification for their belief. That ended up leading into a kind of secular idea of freedom. That wasn’t Luther’s intention, but there’s a way in which he shifts the center of gravity inward into subjective freedom that would generate a lot of the political revolutions that would occur in subsequent centuries.

Descartes is often thought of as inaugurating modern philosophy. We’ve seen this process—going back to the nominalists, through the Renaissance, the Reformation—of the increasing interiorization of thinking, the increasing importance of subjectivity. He brings it to a whole new level.

Descartes was trying to find some way to bring together these warring camps in Europe—he was living, and himself fought, in the Thirty Years’ War, and in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and the birth of modern nation-states. He’s trying to inaugurate a new mode of thought in the midst of a lot of turmoil in Europe. Descartes articulates a method that he hoped would allow for a new sort of shared inquiry, what we now call the mathematical sciences, that might allow for some reconciliation among these warring religious perspectives.

His dualism between the thinking substance and the extended substance, or between the soul and the body, is an attempt to say: okay, religion deals with the soul, but then there’s mathematical science that deals with nature. Whatever religious disagreements we might have, we can all still study nature and arrive at indisputable shared truths using mathematics. And those truths could allow us to harness the power of nature to improve our condition.

For Descartes, mathematics was a kind of divine gift that allowed human beings to understand what would otherwise be a very obscure sensory experience of the natural world, which, like Plato emphasized, is constantly changing. Descartes uses the example of a wax candle. You think it has a form, and you light the candle and then the wax melts. It’s the same material, totally different form. This is a clue to Descartes about how our innate ideas allow us to understand what’s going on in nature even if our senses seem to continually deceive us.

Descartes develops this argument rooted in doubt: we can doubt all of our sensory experience. We can even doubt logic and mathematics, when it comes down to it, because Descartes thought that God was so powerful that God could make 1 + 1 = 7 if God felt like it. But God is good, of course; so God wouldn’t do that. Descartes arrives at the cogito: the idea that the one thing that I cannot doubt is my own doubt, my own thinking activity. So he’s, through a method of extreme and radical skepticism, arriving at a new foundation for knowledge that is actually our own subjective thinking activity. This is a profound discovery.

Now, of course, while he’s usually thought of as a dualist, he’s anchoring the power of this thinking activity—the cogito that he has discovered—in God. And God mediates between our ideas and the mathematical structure of nature. He has a very interesting twist on Anselm’s ontological proof for the existence of God; I think of it more as a phenomenological proof, almost like an experientially grounded proof of the existence of God.

Descartes says: look, we know that we’re finite. I know that I’m a finite being, he says. I make mistakes. I err. I don’t have total knowledge. How do I know that I’m finite? Well, I contrast myself with an infinite idea. Where did that infinite idea come from? I’m finite; I couldn’t have put that in myself. I didn’t come up with this idea of the infinite, or God. Descartes claims he found it in his own experience as a logical correlate of his own doubt, of his self-knowledge of his own limitations. So he reasons himself backward from his own finitude, recognizing that we do have this idea of the infinite in contrast to our own finitude. Then God becomes the guarantor of our human knowledge that reconciles what would otherwise remain a dualism between subject and object. Not entirely satisfying from a contemporary critical point of view, but given his cultural and religious context, it proved compelling.

Many contemporary thinkers in the natural sciences, in trying to understand the nature of human consciousness, will say, “Of course, I’m not a Cartesian dualist.” But there’s so much Cartesian residue in contemporary thinking, even among those who would explicitly deny that they’re thinking in that kind of dualistic way. Whenever we try to understand nature as just matter in motion—no matter how sophisticated the mathematization of that motion may be—and then think of consciousness as something intrinsically irreducible to matter in motion (and to be fair it is hard not to!), we’re still thinking in Descartes’ paradigm. It’s very difficult to get out of that.

Now, the German idealists—from Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel—do try to overcome that dualism and that residue, not by rejecting Descartes, but in a way intensifying the power of the thinking activity that Descartes had discovered but didn’t fully appreciate. But we’ll come back to them next week.

I want to mention the French Revolution. Hegel was a young man when the French Revolution occurred in 1789 and in the years following, and he was really lit on fire by this eruption of political freedom in France. In Germany, this took a more spiritual form through the work of Kant, who was challenging religious authorities by pointing to the inner experience of conscience. Our duty to the moral law is something that only each individual can confront and reconcile themselves with. We can’t, for Kant, rely on external authorities to tell us what is good. We have to rely on our own inner conscience, our own experience of reverence for the moral law.

So what was manifesting externally in the political world in France was, in the German world, as a result of what Kant was arguing about the nature of freedom, experienced inwardly as a spiritual form of freedom. Hegel, and his roommate in seminary, the younger Schelling, and the poet Hölderlin—they were all upsetting the professors at that seminary by championing the values of the French Revolution. The German princes and dukes were quite nervous at this time, too. “Spirit,” as Hegel would later write in the preface to the Phenomenology, “has broken with the world it has hitherto inhabited and imagined.” A “sunburst, in a flash, illuminates the features of the new world.”

What do you think?