Below is a video (talk, then Q&A) and transcript of my talk yesterday for the Scientific and Medical Network. I’m hoping to be able to share the video at a later date.

…

David Lorimer: This evening, we are looking forward to Matt Segall’s talk about Schelling and the return of organic science. There has been significant interest in the Network regarding Goethe and science, particularly reflecting on the contributions of Brian Goodwin who developed the MSc in Holistic Science at Schumacher College. We’ve also had meetings at Regents College, where we engaged in exercises related to science in Regents Park, which were very enjoyable. The role of Schelling in his time was crucial, and tomorrow Matt will join me and Rupert Sheldrake to discuss Andrea Wulf’s Magnificent Rebels, where Schelling plays a pivotal role. The question he will address this evening concerns why the mechanistic view came to dominate over consciousness, a legacy we are just emerging from, which remains very strong. I am very much looking forward to what Matt has to say, speaking from California where he is an associate professor in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness program at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. His book, which I’ve just begun to look at, is titled Crossing the Threshold: Etheric Imagination in the Post-Kantian Process Philosophy of Schelling and Whitehead (2023). Whitehead, of course, is also incredibly important in the history of philosophy. Matt, over to you.

Matt Segall: Thank you so much, David, and thanks to the Network for having me tonight, or this morning for myself here in Northern California. Yes, I teach philosophy, but I feel that philosophy is best done in dialogue with non-philosophy, including natural science, religious studies, spirituality, art, politics, and society. As a philosopher, I am interested in all these domains and consider myself a transdisciplinarian, a thinker who likes to transgress boundaries to connect what has become fragmented. Before we started, David shared a quote from Schelling that I begin my book with, and I think it’s a good place to start, so I’ll share that. Schelling writes,

“Whenever the light of that revelation faded and humans knew things not from the all but from other things, not from their unity, but from their separation, and in the same fashion wanted to conceive themselves in isolation and segregation from the all, you see science desolated amid broad spaces. With great effort, a small amount of progress is made, grain of sand by grain of sand, in constructing the universe. You see at the same time the beauty of life disappear, and the diffusion of a wild war of opinions about the primary and most important things as everything falls apart into isolated details.”

Schelling is writing this in the first few years of the 19th century when mechanistic science was just beginning to take root, and this sense of the human mind as an onlooker upon a natural world that was fundamentally separate from it rather than the view that an organic approach to science would take, that mind is a participant in nature. I am going to dive into Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling’s approach to organic science and give a bit of the historical background and context to understand who he was thinking with and who he was responding to.

As I mentioned earlier, I’m a transdisciplinary thinker, trained in philosophy, but I try to branch out and enter into dialogue with contemporary scientists, among others. My interest in Schelling was somewhat accidental. I was taking a course focused on Hegel in graduate school, trying to understand Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and Science of Logic. I realized I needed to read Kant, of course, but also Fichte and Schelling, among others. As David mentioned, tomorrow he, Rupert Sheldrake, and I will be discussing the book Magnificent Rebels, which delves into the circle of friends around Jena and the University of Jena. To really understand Schelling, or Hegel, or any of these thinkers, you need to read them as part of a community of discourse, really as friends engaged in a shared love of wisdom. Philosophy itself means friendship with wisdom, sometimes just translated as love of wisdom. So, when I was trying to understand Hegel, I went back and read some Schelling, particularly Schelling’s various works on Naturphilosophie, and I fell in love. I am a romantic at heart, and the way that Schelling was able to reimagine the relationship between mind and nature really captured me.

In my own scholarship, my home base is Alfred North Whitehead, who did write in English, though many would dispute that when they attempt to read his work. What I have found, and what I have argued in much of my work, is that Whitehead is really in lineage with Schelling. Not only as a process philosopher, which I’ll go into in a bit, but as a thinker of organism. Whitehead called his own philosophy a “philosophy of organism.” Having already been steeped in Whitehead’s thought, what Schelling was attempting to do in reimagining the relationship between mind and a living nature very much resonated with me. I recognized it as an earlier expression of this organic mode of thought which really culminates in the 20th century in Whitehead’s philosophy.

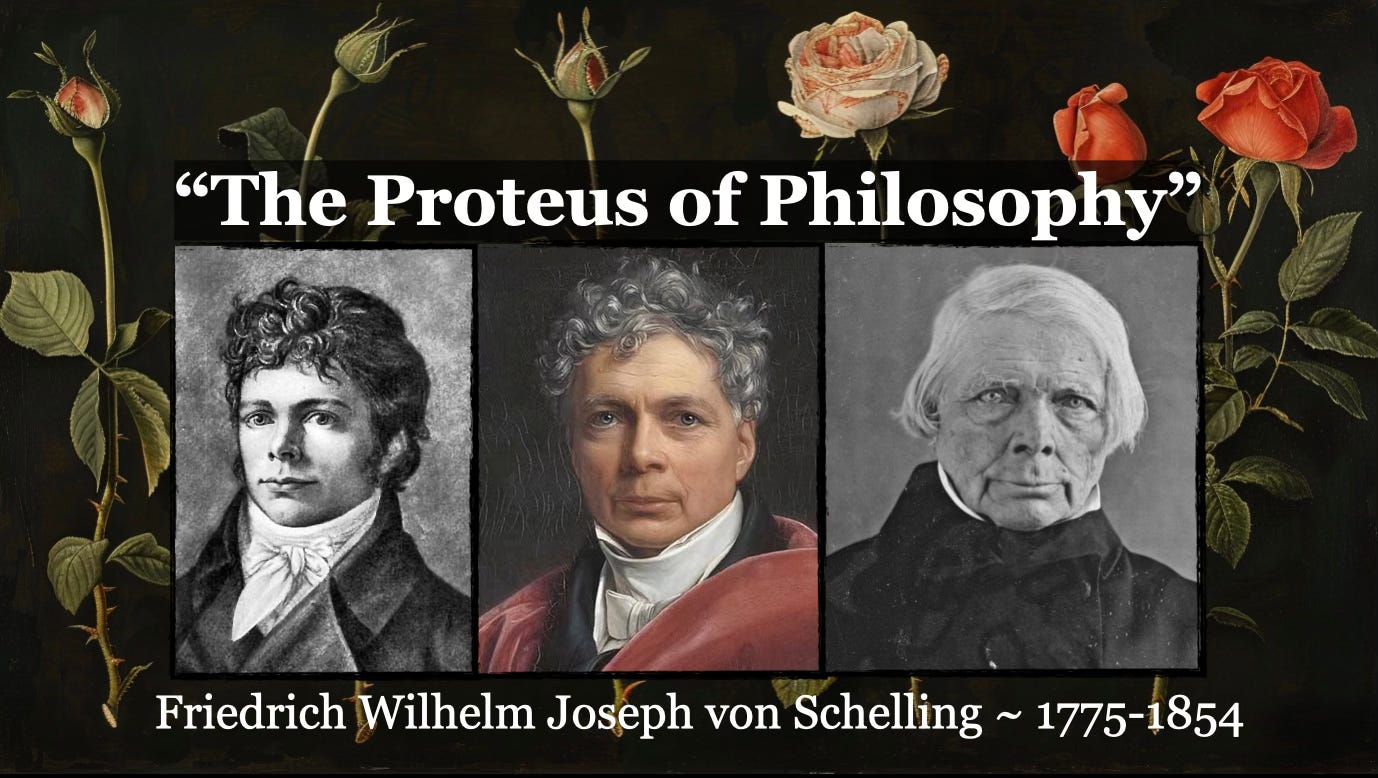

Schelling was referred to as the “Proteus of Philosophy” by Hegel in Hegel’s lectures on the history of philosophy. Hegel meant this as an insult, a kind of disparagement, because he felt that Schelling refused to commit to a systematic point of view and instead just regularly invented new systems throughout the course of his life. But that might also be an unfair caricature, or in fact betray a core difference between Hegel’s approach and Schelling’s approach. I’ll return to this question in a moment.

I want to share just a brief intellectual biography so you get a sense for who this man was, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, who was born in 1775, in Leonberg near Stuttgart, on January 27th, to be exact (just 2 days before my own birthday). He studied Greek and Latin as a very young man, usually with other students who were a decade older than him. By the time he was 15 years old, he was already reading Plato and Aristotle in Greek, and reading Leibniz in Latin. By 1790, when he was 15 years old, he entered the seminary at the Tübinger Stift, where famous thinkers and scientists including Johannes Kepler had attended centuries earlier.

At the Stift, he roomed with Hölderlin, the German poet, and Hegel as well, both of whom were five years older than Schelling. Schelling arrived as a fifteen-year-old, Hölderlin and Hegel were already 20 years old. Within a few years, by 1795, Schelling was already publishing essays in philosophy, responding to another prominent thinker of the time, Fichte, who was quite famous then at the University of Jena, where he began teaching his “Wissenschaftslehre,” his science of knowledge, which centered not only knowledge but all of reality around the human “I” and the act of self-positing that Fichte asserted the “I” is engaged in. All of reality, Fichte would say, spills out from our own thinking activity and our own self-consciousness.

Schelling was quite taken with Fichte initially and wrote several essays at this early stage engaging with his thought. The first one, written when he was only 23 years old, was titled “On the Possibility of a Form of Philosophy in General.” He sent this off to Fichte in Jena. Fichte wrote back, sent him an updated version of the “Wissenschaftslehre,” to which Schelling responded almost immediately with his essay “On the I or on the Ego as the Principle of Philosophy or the Unconditioned in Human Knowledge.” So, as a 19-year-old, Schelling was already engaging with the most prominent thinker in Germany and in Europe at the time.

In 1796, this famous document called “The Oldest System Program of German Idealism” was penned. It’s actually written in Hegel’s handwriting, but scholars agree that the contents of this short fragment most represent Schelling’s thinking. As I mentioned, Schelling, Hegel, and Hölderlin at this time were engaged in a deep friendship and shared interest in philosophy. Some of the things written in this document include, I quote, “What must a physical world be like for a moral being?” Schelling, in articulating this perspective in this document, asks this question. We’ll return to that. He also says he wants to “give wings to physics,” and he says, “I am now convinced that the highest act of reason, which embraces all ideas, is an aesthetic act, and that truth and goodness are only conjoined in beauty.” A very romantic perspective there. And he says, finally, “monotheism of reason and of the heart, polytheism of imagination and of art, this is what we need.” And he adds that he also is seeking a “new mythology,” but a mythology that would be in service of ideas, a “mythology of reason,” as he refers to it. Everything is contained in nuce, really, in this early document. These are thoughts that Schelling will continue to unpack for the rest of his life, for decades to come.

In 1798, he’s 23 years old, and he is invited to teach philosophy at the University of Jena as an extraordinary professor, which means unpaid by the university; he would be paid directly by students who attended his lectures. It was Goethe who interceded on Schelling’s behalf in order to have him hired at the University. It’s kind of unprecedented for such a young man to begin teaching; he would remain at the University of Jena—where he did some of his most important work on the philosophy of nature—until 1803.

During his time at Jena, Fichte was chased out of the university; he was accused of atheism. He was also a sympathizer with the revolutionaries in France, so the government in Weimar was not happy with Fichte; whether or not he was really an atheist is another question. But Fichte had been chased out, and at the same time, Schelling began to articulate a new perspective that was in conflict with Fichte’s focus on the human “I,” the human ego. Fichte thought that nature was just a sort of product of our thinking activity, and Schelling thought that this was not doing justice to the productivity, the creativity, and the autonomy of nature. So Schelling begins writing these works on the philosophy of nature; this upset Fichte, and their friendship ended as a result of this around 1800, 1801. Right around this time as well, Schelling is beginning to fall in love with a woman named Caroline. At the time, she was married to one of the Schlegels, Wilhelm Schlegel. But Wilhelm was quite a gentleman and quite kind to Schelling, and just accepted Caroline was in love with him. So Wilhelm willingly sought a divorce. Goethe again interceded to make this possible, and in 1803 Schelling would marry Caroline. There had already been some tragedy in that Caroline’s daughter from a prior marriage (not with Wilhelm), Auguste, had died in 1800 of dysentery. Schelling was with Caroline and Auguste on a trip when this happened. Schelling ended up being blamed by some critics of his because he lowered the dose of opium that was prescribed to Auguste. It was a big controversy, and Wilhelm actually defended Schelling in print and said no it was not his fault that Auguste died.

Following this tragedy of the death of Caroline’s daughter (who was actually closer to Schelling’s age than Caroline: Caroline was 12 years older than Schelling), Schelling and Caroline get married. They move from Jena to Würzburg in 1803, where they live until 1806. They eventually move to Munich, where Schelling would spend most of the rest of his life. Tragedy followed Schelling, unfortunately, and Caroline also died of dysentery in 1809, just as Schelling is finishing his famous so-called “Freedom Essay” or the Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom. That does get published late in 1809, but Schelling publishes basically nothing after this; he continued to work and lecture, but he didn’t publish a book after the death of Caroline. He was really quite depressed for a while and really began to take a more tragic view of human life.

He did return into the philosophical limelight, however. Decades later in 1841, he came to Berlin to take up the former chair of philosophy that Hegel had vacated when he died a decade earlier in 1831. In these late lectures Schelling offers a series of criticisms of Hegel’s philosophy. These lectures were attended by people like Kierkegaard, Engels, Bakunin, and others. Kierkegaard, in particular, absorbed a lot of Schelling’s criticisms of Hegel and would later go on, in very Schellingian fashion, to describe Hegel’s system of philosophy like an elaborate, beautiful castle erected in the clouds, while meanwhile, Hegel was living in the shack next to it.

So that’s the basic trajectory of Schelling’s life. I wanted to lay that out for you so you get a sense for the person because, you know, as Schelling says in his work Ages of the World—which he wrote multiple drafts of beginning in 1810 or so, but never published—he says:

“the person is the world writ small; one who could write completely the history of their own life would also have, in small epitome, concurrently grasped the history of the cosmos.”

You get this Hermetic sense in Schelling’s philosophy of the human being as a microcosm. And one of the key differences we’ll see between the organic and the mechanistic approach to science is in the extent to which this Hermetic maxim is affirmed. Is the human being a microcosm of the whole? Or is the human being a peripheral accident, our consciousness an anomaly in an otherwise mechanistic, purposeless, meaningless universe?

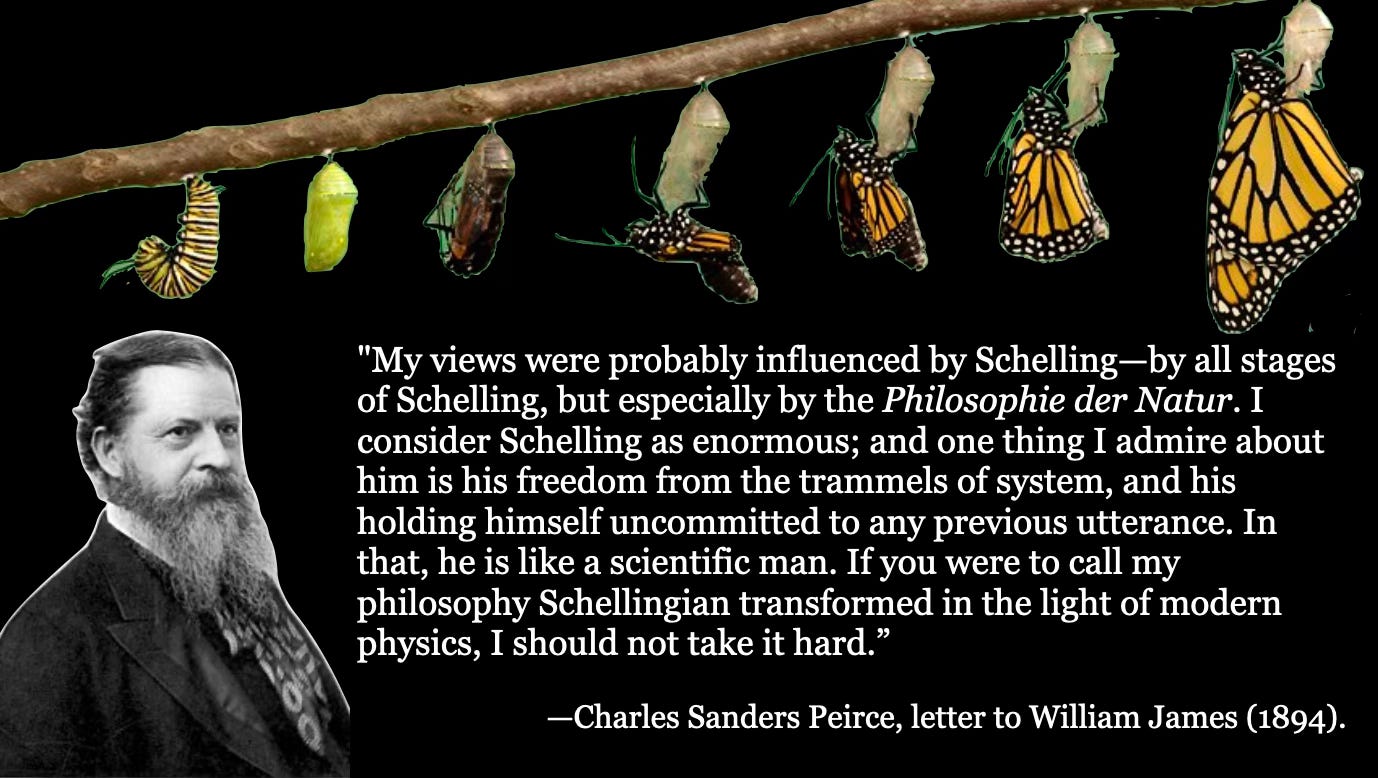

I mentioned Hegel’s quip that Schelling is the “Proteus of philosophy.” For other thinkers, like this man, the American philosopher and scientist Charles Sanders Peirce, an important influence on William James, this idea of Schelling as a Proteus was actually a good thing. This was describing Schelling as a more scientific and experimental thinker. Peirce says in a letter to James:

Peirce is an organic thinker himself, a kind of panpsychist who saw the natural world as a dynamically evolving living organism, not a dead system. Which is to say, the universe is an open system that is still in the process of organizing itself. And so for thinkers like Peirce, and here he’s very much in lineage with Schelling and very much in resonance with Whitehead, physical laws are more like habits which emerge in the course of evolutionary history, rather than being imposed upon the physical world from eternity as if from the outside. And so what for Hegel is a criticism, for Peirce becomes a source of praise.

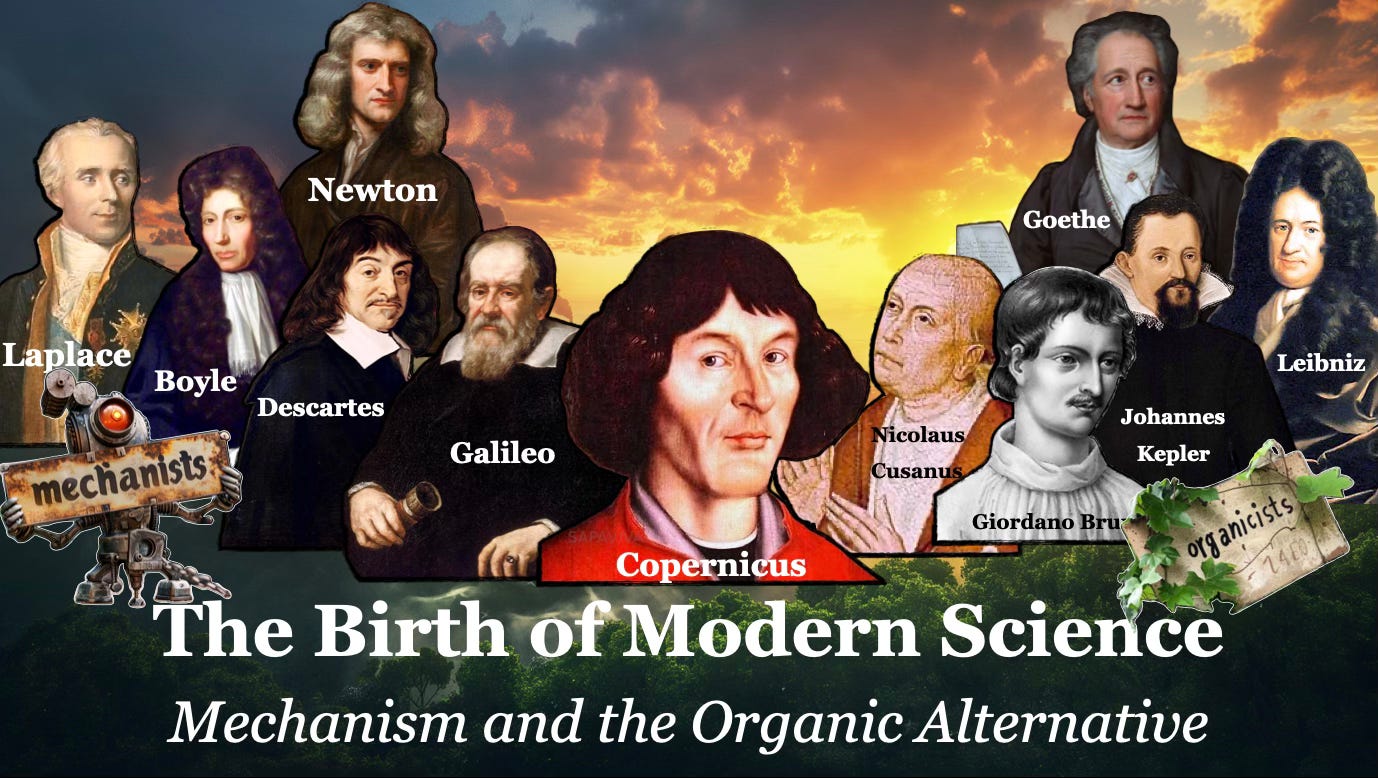

Before we get to the details of Schelling’s philosophy of nature, let’s put his project in historical context. In the 17th century, we have what often gets called the scientific revolution, the birth of modern science. One place to inaugurate this new approach to the study of nature would be with this man, Nicholas Copernicus, who was commissioned by the Vatican in the first half of the 16th century to improve the accuracy of the liturgical calendar.

Copernicus engaged in astronomical research that took him back to some ancient Pythagorean speculations about a heliocentric solar system. And so Copernicus did not invent this perspective; he’s going back to some earlier speculations. One question we might ask is if the mathematics and the geometry of the heliocentric perspective had already been known thousands of years earlier, why did the Ptolemaic model, the geocentric model, dominate in Europe for so long? Well, one of the reasons is that the Ptolemaic model actually was more accurate in its predictions than Copernicus’ initial heliocentric model, and this was because Copernicus’s model assumed that the planetary orbits were perfect circles. It took Kepler to realize that they were elliptical. And so, if Ptolemy’s model is more predictive, why would you switch to Copernicus’? Well, Copernicus’ had more mathematical simplicity, you might say. But there was an evolution of consciousness that needed to take place, and the Ptolemaic model was secure in a context wherein the human mind had no need to sever its sensory perceptions from its rational understanding. In other words, to Ptolemy didn’t claim that the heavens actually moved in the way that his model suggested. It was merely an attempt, as the ancients would say, to “save the appearances.” In other words, what appeared to our naked eye to be the wandering, seemingly chaotic movements of the planets as they go through their retrograde motions could be explained as a more mathematically perfect form of motion by using the epicycles and deferents of Ptolemy’s model. But to say that the heavens really moved that way would be, for the ancient astronomical imagination, to trespass into God’s territory. How God does it we can’t know. But this system, the geocentric model, works well enough for our purposes. What shifts after Copernicus is the sense that maybe the human mind can know how the heavens actually move and maybe our mechanistic models do capture the reality and not merely offer a saving of the appearances. And so there’s a bit more hubris in this modern perspective that in some sense the human being could come to take the perspective of God and know how God did it. You also get this sense in Copernicus and with the emergence of this heliocentric model that there’s a conflict between our sensory perception of the surrounding world—which you know, when you watch the sunset, you very much get the impression that the earth is still and the heavens are moving—a conflict arose between this sensory perception of the surrounding world and our mathematical conception of it, which would suggest that, no, actually the Earth is a planet. The Earth is rotating on its axis and revolving around the Sun with the other planets.

But still, it seems to me that there was a fork in the road here. One path leads to a mechanistic form of science where the mind is divorced from nature, which is one way of responding to this seeming conflict between our sensory perceptions and our mathematical understanding. And the other road leads down the organic path, wherein we can see nature as in some sense a living process and our own consciousness as a function or expression of that larger process. And there really are two streams, two schools of thought here, and there’s a whole alternative form of modern science which could have taken root, which would have been more organic. And these are some exemplars of this alternative organicist approach:

Nicholas of Cusa, who actually speculated about a heliocentric solar system even before Copernicus, and had some conception of the universe as omni-centric. Giordano Bruno was a panpsychist thinker of infinity as well. In the sort of origin myth of modern mechanistic science, Bruno is sometimes described as something of a scientific martyr, burnt at the stake by the Catholic Inquisition for his scientific views, but it wasn’t really his scientific views that led to that. The Renaissance scholar Frances Yates speculates that there was some political intrigue going on and also, Bruno had some heretical theological views. And so it’s a much more complicated picture than the usual story told by, for example, Neil deGrasse Tyson in the revamp of the “Cosmos” TV series, who paints Bruno as this kind of scientific martyr. I don’t think Neil deGrasse Tyson or a contemporary scientific materialist would want to defend Bruno’s panpsychism or practice of the magical arts. Be that as it may, he’s a good exemplar of this organismic perspective.

Johannes Kepler—who I mentioned added the elliptical orbits, this innovation on Copernicus’s heliocentric model which still had the planets moving in perfect circular orbits—was an astrologer, he was an archetypal thinker and developed a musical cosmology and a sense of the planetary orbits as in resonance with one another, realizing a harmony which the human being could intuit. And of course he’s a mathematical thinker, too. But he has this deeper Pythagorean intuition of a universe which is organized according to these harmonious archetypal patterns. And he has a more participatory understanding of mind’s relationship to nature in this sense. Leibniz is another really brilliant organic thinker, a panpsychist who developed a monadology where what nature is really made of are little perceivers. Nowhere in nature is there a true absence of mind, according to Leibniz. And then Goethe, of course, who developed his whole participatory approach to science, an alternative scientific method, which he sought to exemplify in the study of the metamorphosis of plants and the study of color, the study of animal morphology, and many other applications, as well.

So these are the organicists. And there could have been a whole different approach to modern science, no less scientific than the mechanistic approach which ended up winning out. Then there are thinkers like Galileo, who as Whitehead would later argue, bifurcated nature into the primary characteristics which were the measurable parts of the physical world, mass and extension and so on, and the secondary characteristics which would be all the qualitative stuff added by our sensory organs, which are mere appearances, they’re not really part of nature. Now, Galileo didn’t mean to make an ontological statement in this bifurcation. It was more of an epistemological shortcut to allow science to go about measuring the physical world. In many respects Galileo’s descriptions of motion and so on require a bit of mathematical abstraction to eliminate things like friction and all the stuff that say in Aristotle’s version of physics, which was more phenomenological and not as abstract, would still be part of the description. In Galileo, you have to create a ideal model of the system in question by removing a lot of the context to get the math to describe what’s going on. And so Galileo made this epistemological shorthand which this guy, Descartes, turned into an ontological dualism between a thinking substance, namely our own minds—this disembodied “Cogito” which Descartes would famously define with the statement, “I think therefore I am,” but it’s really “I doubt therefore I am”—so you have this disembodied doubtful ego or “I” set against a world of extended matter in motion completely devoid of any soul, any subjectivity or interiority. Then you have Boyle who really transforms alchemy into chemistry; and then you have Laplace and Newton, who perfect the mathematics of motion and gravitation and so on.

So these are the two streams. Why did the mechanists come to dominate? Well, it’s a complicated story. I think there are different versions that we could tell of that story, but one version would be to say that the the mechanistic approach has industrial application. It affords the human being more capacity to predict and control the natural world. At least in the short term. One of the reasons that Schelling is being reconsidered nowadays, and that the whole organic approach to science is enjoying something of a renaissance, is that in the longer term this control and predict approach to nature—as though it were just a mere mechanism or a collection of parts that could be reverse engineered and rearranged as the human sees fit—turns out to have disastrous ecological consequences. A mistaken philosophy of nature has real world consequences. The modern West had imagined that nature could be manipulated as a mere mechanism, and that view is now coming back to bite us.

I could also mention that there are social and political reasons for the dominance of the mechanistic view, because there is a sense in which the rise of Enlightenment conceptions of freedom and individuality were premised upon a contradiction between free human beings and a deterministic natural world. We organized our modern societies around the idea that human freedom depended upon the mastery of a merely mechanical nature. If nature is granted interiority and soul, if it is granted a life of its own and some intrinsic value of its own, then that begins to challenge the autonomy of the individual rational subject and its freedom. And so part of the difficulty here as we try to move away from this alienating form of mechanistic science is to rediscover and reimagine what it would mean to be a free human being in the context of a re-enchanted living and ensouled natural world. That’s not an easy problem. I think it’s a resolvable problem, but I do want to acknowledge the important political reasons that the mechanistic view won out.

So having set the scene and looked at this pivotal moment in European history with the scientific revolution, I want to turn now to Immanuel Kant. And I’m referring to this moment as “the Kantian interval,” or you could refer to it also as “the Kantian compromise,” because I think it’s an unstable position that Kant leaves philosophy in.

After the rise of this new scientific conception of nature as a deterministic mechanism, people begin to worry about human freedom. If the human being is a part of nature, then how is it that our thinking activity and our willing activity is not itself also determined? And there also arose a skeptical criticism of science itself by David Hume. Hume famously questioned the validity of judgments of necessary connection or causality in the natural world. Hume is an empiricist: he says if you observe your sensory experience, nowhere do you observe a necessary connection between, say, two billiard balls hitting one another. What you see and call “causation” is nothing more than a kind of psychological association. And psychological association or habit, as you could also refer to it, is not good enough for the kind of lawful necessary connection that a scientist like Newton would need to provide a mathematical explanation of motion in the natural world. And so Kant reads Hume and says famously that Hume “awoke me from my dogmatic slumber.” Kant realizes we need to to protect science, to come up with a sounder epistemological foundation for it. So Kant asks, what are the conditions of the possibility of natural scientific knowledge? Kant’s solution to this problem was in some sense to accept Hume’s criticism of our empirical experience, but to add a transcendental layer below or behind it. Kant says that Nature appears to us in the lawfully ordered way that it does not because we experience causality through our senses, but because our own mind, our understanding, our capacity for logical reflection, itself requires that we interpret our experience in a causal way. In other words, rather than being just a habit or psychological association, as it was in Hume, for Kant, causality becomes a necessary and universal category in terms of which every human being inevitably interprets their experience. He’s agreeing with Hume that we don’t learn about causality from our sensory experience of the world. But unlike Hume, he’s saying the human mind as it were comes “pre-installed” with causality as an innate or a priori category. And so we have no choice but to make sense of nature in such terms. For Kant, space and time are also what he would call forms of our own intuition. Which is to say, we don’t come to learn about the nature of space and time from our sensory experience. Rather, we cannot experience anything except in terms of space and time, in terms of the sense of external simultaneity provided by space and the internal succession provided by time. These, too, come pre-installed in the human mind.

But Kant thus ends up limiting the knowledge that natural scientists can claim to phenomena, to appearances: what science is telling us is only how nature appears to our kind of mind. Science can’t tell us what nature is in itself, Kant would say. So science becomes limited to a systematic study of phenomena, with the noumenal world or the realm of things-in-themselves left mysterious. As Kant himself famously puts it in the introduction to his first critique, published in 1781, and, in 1787 in a second edition, he says, “I found it necessary to limit knowledge to leave room for freedom.” How did he leave room for freedom? Well, because science can only explain apparent nature or phenomenal nature as deterministic and lawful, that means there’s still room behind the scenes as it were for human freedom.

And so you can see how this is a kind of unstable position, right? Kant would say that the starry heavens above me are lawfully ordered and the moral law within me grants me freedom. But how do the two fit together? How did the subject come to be pre-installed with these categories in terms of which it can organize its experience? What is the thing-in-itself? How can you posit something and at the same time say we can know nothing about it? And so, you know, the Kantian interval is an unstable situation.

But Kant wasn’t finished. There’s the first critique, The Critique of Pure Reason, and the second critique, The Critique of Practical Reason where he goes into trying to find the moral law which he identifies with freedom. But in the third critique, published in 1790, The Critique of Judgment, Kant explores the limitations of his earlier view of phenomenal nature as purely mechanistic. He begins to study the biological world, the world of organisms. While the inorganic world could be explained exhaustively in mechanistic terms, when he looked at organisms, Kant saw a different kind of causality at work. And he famously says, in looking at this the self-organizing dynamics apparent in the realms of plants and animals, that there could never be a “Newton of the grass-blade.”

Newton can explain how the apple falls from the tree, but Newton cannot explain how it got up there in the first place. Why is this? Well, living matter or self-organizing matter displays a form of causality which is not merely efficient, not merely mechanistic in the sense that there would be a linear cause and effect relationship where the cause and the effect are external to one another. In living organisms, the cause and the effect become internal to one another, they become circular. The parts of an organism produce one another for the sake of a whole. And so in some sense, when you’re talking about an organism, the whole precedes its parts because the parts are only there because of the way they’ve produced one another for the sake of that whole. If we’re going to use Aristotle’s terms, this would be a kind of formal and also final causality, which is not present anywhere else in nature from Kant’s point of view, only in the human subject.

So here you have this organic world. It displays purposiveness. It displays spontaneity, self-organization, a form of causality unheard of in the study of mechanisms and in mathematical physics. Because of this Kant argues that there can never really be a proper science of biology. The best we can do is a kind of “as if” reasoning, where we grant a kind of apparent purposiveness to the living world. But really, there must be something else than mere mechanism going on. We’re just not equipped to understand it, Kant would say, because the categories of our mind are mechanistic. In this final critique Kant also explores aesthetics and our appreciation of beauty. And he talks about artistic genius and this capacity as he would describe it for the artist to tap into these formative organic powers of nature in the act of creating a beautiful work of art. When an artist creates a beautiful work of art, it is as if the whole precedes the parts in some sense. But Kant says the artist doesn’t know how they do it. Of course, you know, you need some training to become a painter or sculptor or whatever, but no amount of training is ever going to produce a Mozart or a Michelangelo, etc. There’s something about genius that allows nature to become art. But the artist can’t tell you how they did it. There’s something unconscious about their creative process. The artist can’t give you a procedure or a list of steps so as to reproduce that beautiful work of art. This is why Kant denied that there could be a science of biology because to do so one would need to be able to, as a scientist, participate and intuitively grasp the wholeness of the organisms that one is studying, and then explain methodologically how that had been done.

The German Romantics, Schelling chief among them, read and studied the Critique of Judgment very closely and were quite inspired by it. But they detected in it a shift from Kant’s earlier position. There was a crack in the Kantian firewall. It’s as if in organisms that phenomenal screen that Kant had tried to enclose knowledge behind cracks open and the noumenal realm starts to shine through. What is going on in organisms? This quality that had been reserved for human reason, for the human mind alone, this kind of autonomy and freedom and self-organizing capacity was appearing in in the organic world around us, which from Kant’s point of view is exactly where it should not be! And so Schelling exploits this crack and tries to reconceive all of nature as organic and self-organizing. Goethe also read Kant’s Critique of Judgment very closely in 1790, which was the same year that Goethe’s Metamorphosis of Plants was published. In his study of plant growth, Goethe is exemplifying for us the very methodology that Kant said was impossible. Now, Goethe is an artist, a poet, and also a scientist, right? The fact that he is also an artist is not incidental to the form of science that he develops, a participatory science. And Goethe and Schelling were close friends. Goethe was more like a father figure, or even a grandfather figure to Schelling. They learned much from each other, Schelling from Goethe about this new experimental participatory method, a kind of loving participation in what one is observing, and Goethe learned from Schelling some of the deeper philosophical, epistemological, and cosmological implications of this form of science.

It’s important here to recognize the way in which Schelling moves beyond Kant. Kant’s fundamental question was, basically, what must mind be such that nature could appear to it in the lawful way that it does? And so nature becomes a mere appearance for Kant. The focus is on the organizing activity of the mind. Schelling inverts this question in his philosophy of nature by asking What must nature be such that mind could evolve from it?

To back up for a second, Kant actually describes his so-called transcendental philosophy as analogous to Copernicus’s revolution in astronomy. Copernicus put the sun at the center. What Kant is doing is putting the human subject back at the center, the human mind back at the center of our understanding of the the universe. And so Kant is asking not what is reality?, but What is our own mind and how does it allow for an apparently lawful world to arise? In contrast, Schelling wants to understand the human subject as a participant in nature. And so he is inverting Kant’s question by asking what must nature be such that mind could emerge from it? Well it can’t just be a merely materialistic, mechanistic collection of particles. That is something mind could never come out of. So this question is what drives Schelling toward a more organic conception of nature, so that the universe as a whole is reimagined as itself a self-organizing system.

Kant, from Schelling’s point of view, is beginning somewhat downstream by imagining that our knowledge arises in a situation where our own reflective self-consciousness is severed from the natural world around us. And Schelling wants to say, well, wait a minute, that reflective self-consciousness, that alienated ego is actually the consequence of a process which took place unconsciously, whereby it became so severed. And so natural philosophy, for Schelling, becomes a process of swimming back upstream by trying to remember that original unity. You can’t begin already severed, having grown forgetful of the process by which you became so severed, and then attempt to explain the possibility of knowledge of nature. We have to go back upstream.

Whereas Kant would say the mind and its categories are a priori. Schelling says no, let’s make Nature a priori. Let’s make the human being’s attempt to come to some systematic understanding an echo of the system of the universe itself, rather than that systematic organization being projected onto nature by the mind. Let’s see if the human mind might be a projection of the system of nature.

Schelling articulates the relationship between what mechanistic science had been referring to as “forces” and what in our own experience we refer to as “feelings.” Whitehead will later articulate, I think, the most important innovation in the last 2500 years of metaphysics, this concept of “prehension”—this is just a little aside, but prehension for Whitehead means feeling, and it’s the way in which anything in nature relates to anything else in nature via feeling—and so from Whitehead’s as from Schelling’s perspective, what we mean by a force in the natural world is the same thing that we mean by a feeling in the context of our own experience. Forces are feelings. Nature is bound together in a nexus of feelings, or fields of feeling, you could say. So you can see how he’s trying to close the gap between what we would think of as our own conscious experience and what had been considered just the dead mechanistic exchange of forces in nature. Schelling wants to build a bridge. He wants to understand nature and its forces as akin to the feelings of our own human experience. And that our own human experience is in some sense a higher potency and intensification of the forms of feeling already operative in the natural world. So as I said, Kant’s Critique of Judgment and his exploration of self-organization in the biological world inspires shelling, but Schelling takes it further by overcoming any apparent gaps between physics, life, and mind.

By the way, the whole idea of dead matter is actually one of the most abstract conceptions the human mind has ever invented. No one’s ever experienced or sensed or perceived mere matter. We only experience qualities: tastes, textures, sounds, colors, right? What is “matter”? It would be something supposedly underlying all of that qualitative experience. But it turns out to be actually quite an abstract idea. And this abstract idea of matter as mere extension is really only conjured into existence, from Schelling’s point of view, after we have separated ourselves from all relation to the natural world. Descartes Cogito, for Schelling, is something like a ghost, literally. And again, this this dualism between mind and matter is downstream from a unconscious act of severance which Schelling wants to uncover. All of modern philosophy, Schelling would say, suffers from the same defect that nature is not available to it. Nature is the living ground out of which our own consciousness arises, but this living ground is unavailable to Descartes and Kant.

And so Schelling says, “so long as I myself am identical with nature, I understand what a living nature is as well as I understand my own life.” Schelling goes on to say that the philosopher of nature becomes nature itself philosophizing or autophusis philosophia. That’s what it would mean to do science. Science, natural scientific activity, becomes nature’s own attempt at self-understanding. That’s the core Schellingian idea. And it’s a form of participatory science.

Schelling develops what he calls an account of the “dynamic evolution of nature.” When we observe what appear to be mechanistic causes, say, in the inorganic world or even in our own, organic bodies, Schelling would say, well we need to put that in its larger context. Imagining nature as a dynamic evolutionary system, Schelling is again asking this question, what must nature be like such that mind could evolve or emerge from it? So he tries to distill down what we know as a higher potency in the human mind, to distill it down to its minimal subjective potencies, it’s minimal form, and understand how nature would be composed of these minimal potencies, these mini-subjects as it were. Schelling finds it necessary to imagine that nature is actually a polarity, that nature could not just be constituted by one fundamental force to which all the others could be resolved, because if there was just one infinite force everything would happen instantaneously. There really wouldn’t be anything there, no time, no distinctions anywhere. You need resistance in order for anything, for any form or pattern of organization to emerge and unfold.

Schelling imagines that nature at its most basic level consists of two infinitely opposed forces striving for equilibrium. And every organized product of nature, whether atoms or stars or galaxies or any species of biological organism, is a kind of temporary equilibrium of these forces, like a whirlpool in a stream. It’s important to recognize here that this polarity that Schelling is describing, and that’s also so important in Goethe’s approach to nature, this isn’t a duality. In a duality like Descartes’, mind and matter don’t require one another in order to exist. They’re just totally independent, and for Descartes, he couldn’t figure out how they could ever come to relate if they have nothing in common. Polarity is different: each pole is entirely dependent on the opposite pole to be what it is. There’s a dynamic reciprocal relationship that binds them together. So it’s not a duality, it’s more like a diunity, you might say. And a diunity suggests some kind of mediating third or a kind of trinity.

And so again, Schelling is imagining nature, yes, as these two infinitely opposed forces, but there’s a hidden third that mediates between the two and he associates this with the Trinity, which is also important for Hegel. This Trinity works throughout nature to produce the organized forums that populate it. There is an important influence here from the 17th century German mystic and theosophist Jakob Böhme that I can’t get into now.

So to wrap up, I want to mention some signs of a shift toward a more organic science, and the easiest way to do this would be to refer to a conference that just took place here in Northern California in San Francisco at California Institute of Integral Studies. We invited Iain McGilchrist into dialogue with other scientists and philosophers and a novelist about his hemisphere hypothesis. For McGilchrist, the brain is not the producer of consciousness. The brain is something more like either a receiver or a permitter of consciousness, as he likes to say. It provides a kind of resistance by which this broader cosmic field of consciousness can become aware of itself. And so the brain acts as a kind of filter. And incidentally, one of the ways of understanding this polarity that Schelling sees rooted so deeply in nature would be to recognize the way in which the brain hemispheres are not what produce our experience of reality, but rather that reality in its diunity produces these two brain hemispheres. So it would make sense, in other words, that an organ such as the brain would evolve in the context of a universe driven by this polarity of forces.

So the signs of a shift were evident in the work of some of the scientists that we invited to this conference. I’ll start in the bottom right. Michael Levin, a biologist at Tufts, is doing work on what he calls bioelectricity, which is totally upending the school of neo-Darwinian molecular biology that has dominated for much of the second half of the 20th century. Levin is pointing to the holistic organizing patterns that shape multicellular organisms via what he calls bioelectric fields, such that there’s a kind of memory that’s not stored in the genes or anywhere locally that they’ve yet been able to discover. And it’s completely challenging the idea that the phenotype of an organism can be explained by reference to a blueprint in the genes. I really encourage you to take a look at Michael Levin’s work. He is a self-identified organicist who is showing all that gets left out of a reductionist, mechanistic understanding of life. That, in fact, almost everything distinctive about life is left out if you try to understand it in that way.

To the left of Levin is John Vervaeke, a cognitive scientist who is developing a conception of the human mind that he believes is fully naturalistic, but is rooted in a convergence between two forms of causality, which you could call emergence as well as emanation. He’s drawing on some Neoplatonic ideas about the mind emerging from nature but also emanating in some sense from a domain of possibility which could not be explained merely mechanistically.

Next to Vervaeke is Richard Tarnas, who I know the Network is familiar with. He’s more of a philosopher, cultural historian, and archetypal astrologer whose work offers a different kind of evidence for an organic conception of the universe. Above them is Timothy Eastman, who I think is on this Zoom call, who is a plasma physicist and process philosopher who’s developed a conception of nature as pregnant with possibility, or res potentiae, as he refers to them in his recent book, Untying the Gordian Knot. In that book he’s drawing on quantum physics and complexity science to articulate a conception of the natural world which I believe is very much in concert with which Schelling. Next to Tim is Ruth Kastner, another thinker of quantum physics developing what is called the transactional interpretation, which really does show the limitations of any simple mechanistic account of the natural world whereby things can be explained merely by parts colliding with other parts. There is a kind of holistic causality that goes on that the various phenomena of quantum physics plainly exhibit for us, and she’s really moving the ball forward on that.

There were also some neuroscientists present, Alex Gomez-Marin presented at this conference, as did the neuroscientist Michael Jacob. Both of them are pushing the envelope in the study of the brain and its relationship to consciousness. Michael Jacob for example is pointing out the ways in which our own kind of consciousness, far from being determined by the brain or cranially enclosed, is very much in intimate relationship to our microbiome. And that our sense of being an intelligent and self-aware agent depends upon the precariousness of our existence as metabolic beings embedded in an environment of energy flows. To understand what our consciousness is, you have to put it back into this broader ecological context, including the whole ecosystem in our guts.

So those are just a few signs in the work of these important thinkers of a shift towards or a return to organic science. I think the natural sciences are coming to this point of view on their own. But as I mentioned at the start, there’s also a sense in which the ecological crisis—ecological catastrophe really—is causing reassessment of how we have understood nature and the the whole approach of technoscience as a form of control and prediction of a world imagined to be merely mechanistic. Going about treating the world, the earth and ourselves in that way has really led to a tremendous amount of destruction, and the reconsideration of organic science is necessary not only for theoretical reasons but for ethical and quite practical reasons, namely to avoid extinction, of ourselves and many other species. I’ll stop there and invite dialogue and discussion.

What do you think?