I’m getting to the end of Iain Hamilton Grant‘s book Philosophies of Nature After Schelling. Though Grant doesn’t mention the influence, Schelling‘s search for the “unthinged” in nature was significantly aided by the cosmogony of German mystic Jakob Böhme (1575-1624). The following is an excerpt from a presentation I gave last year on Böhme. I hope to develop the similarities between he and Schelling’s thought in subsequent posts…

—————————————————

“An original antithesis of forces in the ideal subject of nature appears necessary to every construction.” -Schelling (Grant, p. 160).

“The transcendental philosopher says: give me a nature composed of antithetical activities, of which one reaches out to the infinite while the other tries to intuit itself in this infinitude, and from this I will bring forth intelligence for you” -Schelling (Grant, p. 171).

—————————————————

The physicist Basarab Nicolescu, in his book Science, Meaning, and Evolution, distills the essence of Jakob Böhme’s cosmology of divine self-manifestation as “a threefold structure leading to a sevenfold self-organization of reality” (p. 90).

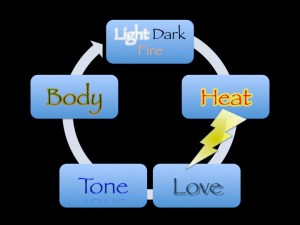

Böhme’s God is not Aristotle’s perfect unmoved mover, but dynamic and self-revelatory by nature. Böhme wrote many books attempting to describe his epiphanic vision of a God who cannot but overflow into creation. God in-itself, traditionally “God the Father,” is the mysterious abyss or ungrounded ground of pre-creation, and consists of the restless agitation of three principles—darkness, light, and fire (or sourness, sweetness, and bitterness, respectively). The light wants to expand and radiate, to become manifest, but the dark wants to remain hidden and self-contained. As a result of the internal friction produced by this self-contradiction, God ignites into flames, burning in what Böhme calls a “wheel of anguish.” The fire of the three restless principles generates heat, which is the first of God’s manifest qualities but the 4th in the sevenfold self-organization of reality. This heat sparks a flash of light, which becomes the force of love in search of itself, the 5th principle. Love finds itself through the reverberation of sound or tone, language or the Word, which is the 6th principle. The Word then becomes flesh, reaching fulfillment as body—God incarnate—completing the sevenfold series.

For Böhme, the cosmos is the body of God. He refers to stars as the “fountain veins of God.” It is as if he is saying that stars are a visible example of this sevenfold creator-creativity in action. This sevenfold series can be understood in a Hegelian sense as moments in the self-development of the whole, a whole that begins where it ends and that is already holographically present in each of its moments.

Cosmogenesis is, for Böhme, the divine’s attempt to find wholeness, and the human being participates in this attempt, our faith (or our opening to the creative and imaginal dimension of reality) acting as the food that nourishes God. Böhme’s cosmology places a heavy responsibility upon humanity, as the completion of the sevenfold cycle depends upon our active cooperation. Without our conscious participation, “the entire universe of the creation would disappear into chaos” (p. 89).

—————————————

Schelling, like Böhme, locates the origin of the universe in the unmanifest darkness of antithetical powers at work in the Godhead, as yet unconscious. This dynamic darkness overflows itself, creating the phenomenal world, which develops through a sequence of stages (Stufenfolge) that provide for God’s increasing self-awareness through corporealization. God was not content to be in itself, since in itself divinity remains unmanifest and merely ideal; God took on the finitude of the sensory world in order to become for itself. Though nature does not begin, for Schelling, as body or bodies (universal substance or particular substances), it would appear that corporealization is nonetheless nature’s (or God’s) end.

What do you think?