A transcript of my talk at the Cognizing Life conference in Tübingen, Germany July 18, 2025.

Other contributors at the Cognizing Life conference include: Benjamin Bembé (Witten), Bohang Chen (Zhejiang), Luke Fischer (Sydney), Andrea Gambarotto (Wien), Levi Haeck(Ghent), Craig Holdrege (Ghent, NY), Christoph Hueck (Tübingen), Philippe Huneman(Paris), Jan Kerkmann (Freiburg), Dalia Nassar (Sydney), Daniel Nicholson (Fairfax), Gregory Rupik (Toronto), Ulrich Schlösser (Tübingen), Matthew Segall (San Francisco), Joan Steigerwald (Toronto), Georg Toepfer (Berlin), Gertrudis Van de Vijver (Ghent), Denis Walsh (Toronto).

See also my responses to a (rather reductive!) geneticist. I draw on some of the ideas of Denis Walsh, who I was thrilled to meet in Tübingen, regarding the bankruptcy of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis and need for an Extended Evolutionary Synthesis.

Host:

Okay, thank you everyone. We’ll make a start. I’d like to have everyone’s attention. So, for our next talk, our speaker is Dr. Matt Segall, who is a transdisciplinary philosopher and associate professor in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. His recent book is Crossing the Threshold: Etheric Imagination in the Post-Kantian Process Philosophy of Schelling and Whitehead, which I think we’ll get a taste of today. The title of Matt’s talk is “Revitalizing Evolution: Whitehead’s Organic Realism and the Return of Romantic Science.” Thank you.

Matt Segall:

Hey, everyone. I’m so excited to be here. I’m glad to be speaking today, having absorbed so many of the talks already delivered. When I was invited by Christoph, I started writing a paper for this that ballooned into 30,000 words, so my challenge was to winnow it down into something I could present in 45 minutes. There’s a lot on Kant in this paper, a lot on Schelling, a lot on Charles Sanders Peirce, who I might bring up later. But because Whitehead has only been tangentially mentioned yesterday by Dan, I figured I’m going to zero in on that. Still, the Romantics like Novalis and Schelling will be in there as well, as you’ll see.

So, “Romanticizing Evolution” is the title of the paper, and I get that notion of romanticizing, of course, from Novalis, who says that “the world must be romanticized. In this way, its original meaning will be rediscovered. Romanticization is nothing but a qualitative realization of potential. The lower self is identified in this operation with a better self, as we ourselves are such a qualitative series of empowerings. This operation is as yet quite unknown.”

The mechanical impoverishment of our understanding of life is precisely what Novalis sought to remedy when he called for the world to be romanticized. For Novalis, this operation—which, as he noted, was as yet quite unknown—meant rediscovering the world’s original meaning through a qualitative realization of potential, whereby human consciousness is progressively transformed through an integral communion with nature that is just as artistic and religious as it is scientific.

To romanticize nature is not to project human sentiment onto dead matter, as if to re-enchant the world by an effort of will alone, but rather to recognize and feel our inseparability from nature. Life is not an accidental byproduct of physics and chemistry, at least if these disciplines are understood mechanistically (if we understand them semiotically, with Peirce, it would be different). Rather, dead matter presupposes life: all enduring substance on the earth and in the wider universe is a byproduct of a primary organization or universal organism. As Schelling put it: “The world is an organism, and a universal organism is the very condition of mechanism.”

So, to romanticize the world is to continually remind oneself that knower and known partake of the same living process of realization. Novalis, like Schelling, was for a time a devoted student of Fichte, and also, like Schelling, came to reject Fichte’s conception of nature as simply a “not-I” or passive object. Novalis, instead, postulates of nature, “Statt Nicht-Ich—Du”; “Instead of ‘not-I’—you,” thus relating to nature as to an intimate friend.

Contemporary academic philosophy has until recently largely ignored both Novalis’s alchemical vision of science and Alfred North Whitehead’s similar call to enlarge the imagination of scientific specialists, remaining instead aligned with the dominant technoscientific research culture, promoting epistemology as a tool of prediction and control rather than fostering relational engagement with living beings and the earth.

To quote Whitehead, he envisions philosophy as “the welding of imagination and common sense into a restraint upon specialists and also into an enlargement of their imaginations.” He continues: “By providing the generic notions, philosophy should make it easier to conceive the infinite variety of specific instances which rest unrealized in the womb of nature.” (That’s from the introduction to Process and Reality.)

Modern biology still defaults to a mechanistic conception of causality that treats organisms as externally shaped collections of purposelessly varying parts. But this stance cannot explain the origin of living form, nor the conscious cognition of the scientists who study it.

Yet, as Western civilization becomes increasingly aware of the dire ecological and social consequences of its predominantly mechanistic and dualistic modes of thought and practice—and as 21st-century science continues to advance beyond the reductionistic methods and metaphysical presuppositions informing the 17th-century scientific revolution—contemporary scholars and scientists are taking another look at the organic and participatory approaches of figures like Schelling and Whitehead, each of whom was prescient in seeking alternatives to modern science’s inadequate and ultimately suicidal conception of nature.

Before I get into Whitehead’s ontology, I want to speak about the reigning cosmological vision—the Big Bang. Often in scientific textbooks, you’ll find depictions like this, and then the human being is thought to emerge at the end, imagining the whole process. So this sort of Big Bang cosmology is the contemporary heir to the Laplacian nebular hypothesis. It offers us an image of cosmic origins, where blind physical forces turn out stars and planets, culminating as an afterthought in conscious human beings. This theory, this story, this myth, severs our moral and aesthetic participation in life from its so-called physical explanation, leaving we sensitive, intelligent creatures as aliens on our own planet—anomalies in an otherwise well-behaved, law-abiding cosmic arena.

What’s disavowed in this view, but never truly absent, is the tacit assumption of the observer. These theories always rely on a hidden premise—the presence of the experimenter or the theorist standing outside the phenomena, manipulating or witnessing from some godlike vantage point. Who is this guy, found in so many physics textbooks, blowing up the balloon to illustrate the expansion of space? There’s always an observer, human or otherwise, animating the display. And yet, we’re asked to believe human consciousness emerges only at the end of this purposeless explosion—not as a co-creative participant, but as a meaningless byproduct.

This is, in truth, a kind of demonology in denial. The materialist cosmos pretends to exclude spirit, but it can only function by covertly invoking it in the form of a giant disembodied head floating beyond space and time, setting things in motion and watching them spin. Quite obviously, we can’t imagine a beginning without already imagining it. Consciousness is not an accidental epiphenomenon of the universe, but is the condition of any cosmological reflection. To model the cosmos, we must already be alive and awake inside it—and it inside us.

Rather than suppress this as an inconvenient truth, a participatory science would acknowledge and even celebrate it. If we are to speak of origins, let us speak not just of forces but of formative aims. Let us do our demonology—or our angelology, as it were—consciously, instead of deceiving ourselves by mistaking toy models for concrete reality. The origin of the cosmos is not just a giant explosion out of nothing, but the expression of a profound yearning to become—or at least that would be the participatory, Romantic vision I am offering here.

So, for Schelling, as Dalia Nassar just shared with us, and for Alfred North Whitehead—who, I think, in many ways is inheriting the organic vision of the cosmos that Schelling developed—human reason is not self-grounding. It is dependent at every step and with every breath upon a vague but intuitive experience of what Whitehead called “the dark universe beyond.” As Joan Steigerwald puts it in her wonderful book Experimenting at the Boundaries of Life, the philosophy of nature acts as a limit of idealism by drawing attention to a dark presence in cognition that defies conceptual analysis. The transcendental structure of the rational mind and the intelligible structure of phenomenal nature alike emerge from the unprethinkable, infinite depths of divine, natural yearning.

Whitehead, in his book Adventures of Ideas, offers us this story—though the quote is cut off here—where he says, “Philosophy must rescue the facts as they are from the facts as they appear.” He writes, “We view the sky at noon on a fine day. It is blue, flooded by the light of the sun. The direct fact of observation is the sun as the sole origin of light and the bare heavens. Conceive the myth of Adam and Eve in the garden on the first day of human life. They watch the sunset. The stars appear, and lo, creation is widened to man’s view.”

Whitehead adds that the excess of light discloses facts and also conceals them. He’s quoting the Romantic poet Joseph Blanco White, from his poem “Night,” which was dedicated to Coleridge and which Coleridge admired. I’ll read the rest of that poem:

“Who could have thought such darkness lay concealed within thy beams, O Sun? Or who could find,

Whilst fly and leaf and insect stood revealed,

That to such countless orbs thou mad’st us blind?

Why do we then shun death with anxious strife?

If light can thus deceive, wherefore not life?”

This excess of light that obscures the fullness of the natural world is characteristic, I would say, of the Enlightenment attitude that manifests both in classical empiricism—leading natural science to focus on the surfaces of objects in empty space—and in classical rationalism, leading idealistic philosophies to focus on clear and distinct ideas in the mind. This emphasis on light neglects our own role behind the scenes, as it were, as sensitive participants.

Rather than maintaining the pretense of being a neutral observer—or worse, the director of the whole show—a participatory method inspired by what we might call the Romantics’ “lunar” or “night” knowledge brings the subject onstage as one of the actors. As Whitehead is reported to have said to Bertrand Russell (and Russell relates this story in his autobiography): Whitehead said, “Bertie, you think the world is what it looks like in fine weather at noonday. I think it is what it seems like in the early morning when one first wakes from deep sleep.”

This Romantic attitude allows natural science to include the subtlety of imaginal subjectivity in its apprehension of nature, bringing balance to the excoriating light of objectifying rationality. Whitehead’s cosmology does not begin with an abstract, toy-model understanding of the physical world and then try to derive life and mind from that abstraction. Rather, he begins where we are, as civilized beings inhabiting a living earth. As he says, “Our datum is the actual world, including ourselves. And this actual world spreads itself for observation in the guise of the topic of our immediate experience.” He wants to offer a philosophical account that would be a modern rendering of the oldest civilized reflections on the development of the universe from the perspective of life on this earth.

Rather than beginning with lifeless matter, he wants to begin from where we are as conscious living beings and understand what the universe must be like such that it could have produced us. Similar to Schelling’s project.

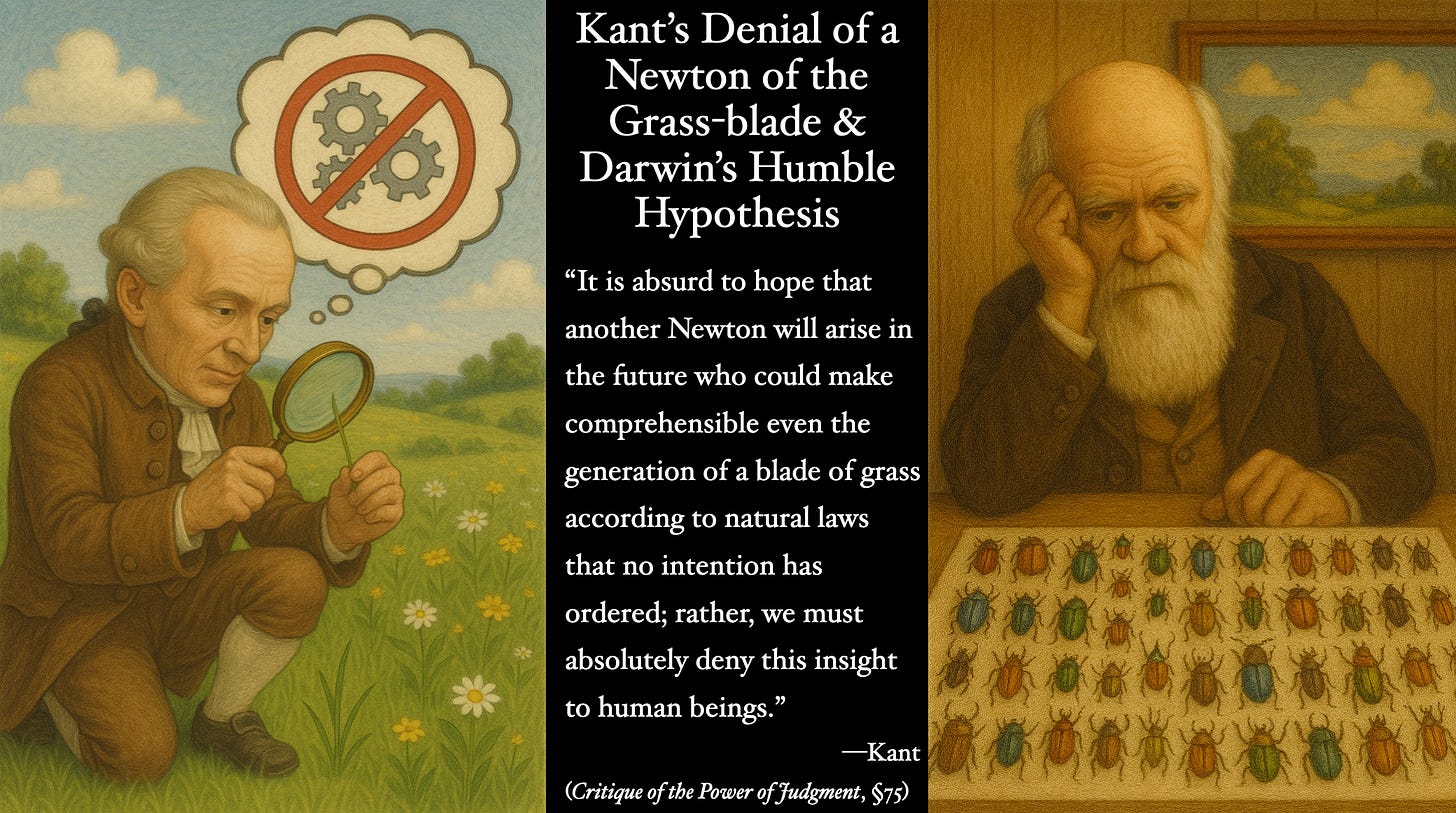

I won’t belabor this whole question, because it’s been discussed at length already by a number of speakers. But, you know, it’s often claimed that Darwin was precisely the Newton of biology that was forbidden by Kant, who foolishly attempted to legislate the limits of scientific advance from his philosophical armchair. But Darwin never set out to reduce living organization to mechanism in his Origin of Species. Darwin presupposes, rather than explains, the spontaneous variations that appear with every generation of living being. Darwin’s genius was to notice that once such variations exist, differential survival in a struggle for existence can gradually accumulate functional novelties.

Darwin was keenly aware of the limitations of his account of natural selection. In the closing summary of Origin, he confessed, “Our ignorance of the laws of variation is profound.” He noted that acquired traits might sometimes be inherited—the dreaded Lamarckism—and he marveled at mysterious, correlated variations that transform whole organ systems during development. These ontogenetic dynamics, he conceded, are “not closely checked by natural selection.” In a wonderful paper titled “Pure Variation and Organic Stratification and Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology,” Jérôme Rosanvallon captures the historic break represented by Darwin as an anti-mechanist, actually. Darwin’s working within the Newtonian context, but Rosanvallon points out that whereas the Newtonian-Galilean paradigm assumed that things maintain their state of motion unless externally constrained (inertia), Darwin is assuming that everything tends to vary unless constrained. So this “variation first” approach actually represents a profound inversion of classical physics, replacing conservation with creativity as the ultimate principle.

Just a little aside about autopoiesis and this approach to understanding life in terms of constraint-closure and self-organization coming out of Kant: Autopoietic theorists tend to maintain a sharp explanatory division between the neutral, purposeless realm of chemistry and physics and the normative realm of biology. The Schelling-Whitehead-Romantic lineage I’m describing here discerns a gradient of aims operative throughout cosmic evolution, as Dalia explained to us earlier. What appears as blind mechanism at one level of analysis reveals itself as low-grade purposiveness when viewed from a synthetic perspective. So, physical laws, from this point of view, themselves become evolutionary achievements—habits of cosmic becoming crystallized over eons.

From this perspective, it’s not possible to construct a world of purposes, meanings, and directed processes using only the resources of blind spontaneity and mechanical filtering. This is why Darwin’s humble acknowledgment that he presupposes, rather than explains, variation is so philosophically significant. It implicitly recognizes that the creative, self-organizing capacity of life draws on metaphysical wellsprings deeper than any mechanism can fathom.

Schelling and Whitehead deepened Kant’s insight by showing how purposive organization is not a late achievement of biological beings but pervades nature from the dawn of creation. To exist at all—whether as an electromagnetic pulse or as a pulsating cell—is to experience some subjective aim that guides the historical process of real actualization out of indeterminate potentiality.

On this view, Darwin’s variation-and-selection principle operates within a more fundamental purposive matrix. Physical laws themselves express low-grade purposes, forming habitual patterns that have achieved stability through cosmic evolution. The principle of least action, evident in the raying of light, for instance, already exhibits nature’s aim at optimal realization. As Whitehead puts it, “There is a harmonized adjustment at work in the action of light.” In Science and the Modern World he adds, “The beauty and almost divine simplicity of least action equations is such that these formulae are worthy to rank with those mysterious symbols which in ancient times were held directly to indicate the supreme reason at the base of all things.”

Novalis says that light is the vehicle of the universe’s communion: “Light is in every case action. Light is, like life, an effect that effects, revealing itself only when the proper conditions converge.” So, light sets the scene for sight. Living organisms feed on and intensify light’s primordial aim, achieving unprecedented levels of creative self-consciousness and freedom. Natural selection shapes the specific forms this creativity takes, but it does not create this luminous tendency itself.

In the Critique of Pure Reason, as we all know, Kant proposes a Copernican revolution in philosophy: objects must conform to the a priori forms of our cognition, not the reverse. This maneuver secures synthetic a priori certainty for mathematical physics—but at the cost of scientific realism. What physics knows are phenomena manufactured by the mind’s categories, applied to spatiotemporal intuitions. As Whitehead quipped, “We never know the real things, but only an edition deluxe expurgated in rationality.”

Rather than positing transcendental subjects who construct the appearance of an objective world, Whitehead inverts—but does not wholly reject—Kant’s Copernican revolution. Where Kant sought the a priori conditions under which human experience is possible, Whitehead asks a more generic question: How are any actual entities possible, given the concrete relations they presuppose?

Subjectivity for Whitehead is not an original structuring principle imposed upon a passive manifold of sensation, but an emergent achievement within the ongoing world process. He thus reconceives the subject as a “superject,” an outcome of the process of concrescence (which I’ll explain in a moment), rather than a precondition for it. In this sense, Whitehead preserves the spirit of transcendental philosophy by seeking the structural conditions of experience, but transposes these conditions from the formal operations of a solitary mind to the concrete genesis of nature itself.

In the terms of his philosophy of organism—what I have elsewhere called his “descendental” method—the subject, I quote Whitehead, “emerges from the world, a superject rather than a subject.” In other words, like every organic creature in nature, we create and come to know ourselves as subject-superjects, by actively organizing a real togetherness of formerly alien things—which is part of what the process of concrescence achieves. I’ll unpack that term now.

Whitehead’s organic realism thus allows for the reintegration of what Kant had torn asunder. To quote Whitehead, “ending the divorce of science from the affirmations of our aesthetic and ethical experiences by planting the self-conscious power of reason back into the cosmic context from which it originates.” In his first lecture at Harvard, delivered in September 1924, which was also his first lecture as a philosopher at Harvard, Whitehead writes: “The process of cognition is merely one type of relationship between things which occurs in the general becoming of reality. Kant asked, ‘How is cognizance possible?’ I suggest to you the more general question, ‘How is any particular entity possible, having regard to the relationships which it presupposes?’”

Every entity that emerges in cosmic history places on the rest of the cosmos an obligation to make room for it. For example, apart from the patience of the systematic coherence of the electromagnetic field required by its electrons, there could be no animal organism, even for a billionth of a billionth of a second. Every entity must be studied in the context of a sheltering environment, providing some systematic character essential to the very nature of the entity in question.

Contemporary biological practice increasingly validates this insight. As Dupre and Bertolaso demonstrate, process-oriented scientists now recognize that the dynamics at any level of biological organization cannot be separated from the coupled dynamics of all other levels, including the environment within which the system is embedded. This ineliminable context-dependency reveals that organisms are not discrete entities with properties, but nexuses of multiscale relationships.

The idea of an organism independent of spatiotemporal relations—or independent of electromagnetic and gravitational fields—is meaningless. Any attempt to classify organisms by means of special properties supposedly isolated from their physical environment obscures the fluid togetherness of things. The essence of life is inseparable from its cosmic history and habitat.

As Whitehead says (and Dan Nicholson quoted this, or at least had it up on one of his slides yesterday), “The doctrine that I am maintaining is that neither physical nature nor life can be understood unless we fuse them together as essential factors in the composition of really real things whose interconnections and individual characters constitute the universe.” He continues: “This sharp division between mentality and nature has no ground in our fundamental observation. We find ourselves living in nature.” Our datum is the actual world, including ourselves, as he said earlier.

So, the fundamental challenge confronting an organic natural philosophy is that living beings exhibit a mode of causality proceeding from wholes to parts—a formative inwardness that unfolds through time—whereas our discursive, mechanistic understanding can only explain phenomena through additive, external relations of parts. In organism, parts produce one another for the sake of the whole that transcends mere summation, at least for the duration of their lives. Once an organism dies, its physically manifest wholeness dissolves, and its component parts return to a merely mineral existence.

This presents natural philosophers with what I’m calling an onto-epistemic challenge: in determining what we can know about the nature of the organic, we are already presupposing its mode of existence, since our organs of cognition are themselves expressions of it. The organic is thus both the subject and object of inquiry—both knower and known. To think life is to be implicated in its becoming, to participate in its self-reflection. This recursive condition challenges the detached stance of mechanistic epistemology and demands a participatory mode of thought equal to the phenomenon it seeks to comprehend.

Whitehead’s response to this challenge reveals a path forward that neither privileges epistemology over ontology nor the reverse. He accounts for the subject-object relationship in a way that extends beyond human cognition alone, as we saw. His position is that the kinds of entities that exist should already tell us what we need to know about the nature and scope of knowledge. Knowers must be among the entities that exist, with those entities being construed so as to be capable of the relation of knowing—at least in their highest grades or at their highest intensity, to use Schelling’s term. In Whitehead’s terms, “The epistemological difficulty is only solvable by an appeal to ontology.” So, any coherent account of what there is to be known must also reveal how we can know it. Knowledge thereby comes to be understood as an adjunct within things known, rather than as a Cartesian or Kantian “view from nowhere.”

Whitehead thus departs from Kant’s focus on human cognition, instead seeking to understand how any relationship is possible—not just the mind-world cognitive relationship that preoccupied Kant. Whitehead’s fundamental question becomes: What is an object if to be an object is always to be internally related—that is, subjected to everything else, including but creatively transcending the past, as what he calls a “superject”?

Each novel actuality arises from an asymmetrical, prehensive process he terms “concrescence,” wherein, as he puts it, “the many become one, and are increased by one.” Now, I mentioned this term “prehension.” Prehension is a process of appropriation—Whitehead uses the synonym “feeling” for this process of prehension. It’s how what’s over there becomes here. It’s a process about the transmission of vectors, and he builds an analogy from electromagnetism to our first-person experience: nature is a nexus of relationships made up by the transmission of feelings. For Whitehead, a pulse of electromagnetic radiation is the conveyance of some emotion—it’s not conscious, but nonetheless, he’s trying to undo the bifurcation of nature between the way our nature appears to us and how science would describe it in terms of electromagnetic waves. Whitehead wants to bring these two parts of nature back together again. So, his account of prehension is a concept meant to unify causality, perception, memory, and so on. Charles Hartshorne thinks that prehension is one of the most important concepts in the history of metaphysics.

So, “concrescence” is a phrase which literally means “growing together”—concrescere. It captures the heart of this process: “the many become one and are increased by one.” The “many” refers to all the existing actual entities in the universe that this newly arising experience is drawing from—every prior moment, every influence, every pulse of cosmic history that somehow touches this moment. “The many become one” means that all these influences get integrated into a single unified new experience. “And are increased by one” means that once this integration is complete, there is now another actual entity in the universe that didn’t exist before and that cannot be undone.

So, experience, never the same twice, takes on an object–subject–superject vector character. Whitehead insists that this process is not merely additive; it is cumulative. It’s not static or spatial but dynamically evolutionary, with each new member of the many containing the whole prior cosmic community and recapitulating it. Consequently, the universe grows like a developing embryo—from one to many, and from many back to one—rather than beginning as preexisting parts that algorithmically assemble into larger structures.

Whitehead terms this his “cell theory of actuality,” envisioning a universe where the whole is continually iterated upon, accumulating novel wholeness, actual occasion by actual occasion. This is not unlike Leibniz’s idea of monads, except for Leibniz, the monads are windowless, and for Whitehead, his actual entities are almost all window—they are internally related to all the prior entities in their past. So, there are real relations in Whitehead’s account of these actual entities, unlike in Leibniz, where there was the need for a preestablished harmony.

Kant sought to navigate a careful path between an empiricist “physiology of reason” and a rationalist preformation system. In his critique of Locke, Kant warns that if we treat the categories as products of a physiological process—that is, if reason is merely an effect of sensory impressions acting on a passive or merely associative mind—then we lose the transcendental necessity that defines a priori knowledge. At the same time, he rejects the notion that the categories are simply innate or preformed blueprints. Instead, Kant proposes an epigenesis of pure reason—a generative, self-productive power by which the mind actively brings forth the forms of cognition from its own inner free play in response to the passive material of sensation.

Yet, for Kant, this epigenetic creativity is merely formal—strictly limited by what is given by the physical senses. The mind produces its own categories and forms of intuition, but it cannot create new sensory content, nor penetrate to supersensible realities through imagination alone.

Now, Schelling, Whitehead, and, as we’ll see, Rudolf Steiner, extend Kant’s nascent insight by refusing to let reason remain an abstract legislator above the streaming of nature. For Schelling, human thought is itself the flowering of nature’s dynamic striving. For Steiner, the physiology of the inner sense promises to disclose the supersensible formative forces that shape both organic nature and our own thinking mind.

For this Romantic lineage that I’m constructing, the cogito is not merely a logical condition, as it remained for Kant, but the highest potency of nature’s own self-becoming—an amplification of evolutionary creativity already unconsciously working at every scale of cosmogenesis.

Goethe intuited this deeper continuity. Through careful, sympathetic observation, he identified unique archetypal phenomena in the metamorphosis of plants, colors, and animal forms, cultivating what he called “exact sensorial imagination”—a participatory mode of observation by which the observer inwardly conforms to and recreates the formative activity at work in the observed. For Goethe, to see the plant aright is to inwardly enact the same metamorphic power shaping its growth, feeling the living archetype within one’s own cognition.

In an article published a few years ago in the journal Dialogue, edited by Troy Vine, I compared Goethe and Whitehead and described how Whitehead’s account of prehension (which I mentioned earlier) provides a metaphysical account of how what Goethe is doing might be possible. So, Whitehead takes this participatory, epigenetic insight and cosmologically generalizes it. What for Kant was the epigenesis of pure reason—mind generating its own categories and forms of intuition—Whitehead recasts as the process of concrescence: the self-creative, evolutionary advance of the universe itself, where every actual occasion at every scale is a synthesis of inherited actuality (what he calls “physical prehension” or “physical feelings”) and imaginal potentiality (what he calls “conceptual prehension” or “conceptual feelings”). A conceptual prehension is a feeling of a possibility; a physical prehension is a feeling of an actuality.

In Whitehead’s scheme, what occurs in the mind and in the roots of prehensive transmission running through our own living bodies—a creative fusion of memory and anticipation, of the perished past and possible futures—is a microcosmic intensification of a universal, archetypal power. Concrescence is not merely a model for subjective thought or experience, but the fundamental mode of cosmogenesis—the dynamic archetype by which all things, from atoms to animals to galaxies, arise and perish.

In this sense, Whitehead’s philosophy of organism can be said to offer a “cosmic phenomenology” of concrescence: an account in which the epigenetic creativity that Kant reserved for reason, as the source of the necessity and universality of our discursive understanding of a merely apparent nature, is recognized as a universal principle pervading actual nature. The mind—our own imaginative thinking activity—is no longer a denaturalized and acosmic spectator of a merely apparent world, but a direct participant, an expression of the very process by which nature becomes conscious of itself.

Recent commentators on the Goethean method of participatory observation of nature, including Eckart Förster and Dalia Nassar, have emphasized its importance for the future of scientific research. Whitehead’s concept of concrescence could be fruitfully compared to what Goethe called the “Urphänomen.” In Dalia Nassar’s terms from her new book, Romantic Empiricism, the Urphänomen does not simply exist in nature, but it is also not merely the achievement of the knower alone. Rather, the Urphänomen is the achievement of the knower in collaboration with nature.

If Goethe’s archetypal phenomenon is the empirical summit, where discursive explanation gives way to direct imaginative seeing, Whitehead’s concrescence is the cosmological Urphänomen—the living form of that same summit enacted at every scale of cosmogenesis. Each actual occasion gathers a differentiated manifold of prehensions, orders them in a hierarchy of felt affinities, and subordinates them to the lure of a final, unifying satisfaction.

In Förster’s terms, each actual occasion thus recapitulates “the intuition of the different as identical, revealing in its own brief arcuration the highest absolute idea constituting the internal nexus of the whole.” (Now, Förster doesn’t mention concrescence, but I’m drawing on his account of Goethe to show how similar it is to Whitehead’s account of concrescence.)

Where Goethe invites the physicist to rest at the threshold of the sensible and hand the finished Urphänomen to the philosopher, Whitehead, the speculative cosmologist, shows that the threshold is potentially everywhere, continuously traversed—beheld by the sympathetic human eye, the universe is forever handing itself over, moment by moment, from knowledge to being, from physics to metaphysics.

Concrescence is the process by which the supersensible flashes into the sensible—the imaginative means by which we catch a glimpse of the living etheric cosmos. To follow its movement with exact sensorial imagination is to practice the scientia intuitiva, the intuitive science that Goethe borrows from Spinoza. This is a disciplined ascent from the plural facts of experience to the unifying idea immanent within them.

Whitehead thereby furnishes Goethe’s intuitive scientific method with a metaphysical grammar. By showing that the mind’s epigenetic power is a special inflection of cosmic creativity, his philosophy of organism entrains our imagination to the productive pulse of the cosmos.

As Christoph Hueck insists, such an entrainment of the inner rhythms of thought with the outer rhythms of being requires imaginatively penetrating into the flow of time itself—not just chronological, clock time, but the lived temporality that weaves memory and anticipation into the prehensive texture of our moment-to-moment experience. Living organisms, like the act of knowing, unfold what Christoph calls a “double stream of time” in which the past is not merely behind and the future not merely ahead, but both are eternally co-present as latent conditions of becoming.

This temporal intuition has far-reaching consequences relevant to this presentation. It vindicates the scientific importance of the human I—the human ego—as Fichte’s original breakthrough in the Wissenschaftslehre suggested. For Fichte, the “I” is a self-positing, self-intuiting being that discovers its own existence in its deed. For Schelling, Fichte’s insight blossoms into a philosophy of organic nature in which subjectivity is nature’s self-revelation. Whitehead universalizes this same dynamic: every actual occasion is a miniature “I,” the germ of consciousness—a momentary, self-creating creature that both receives and reshapes the world. Human consciousness is thus a concentrated exemplar of an ubiquitous concrescent activity, not an anomalous spectator.

It is instructive at this point to revisit Kant’s starting point in developing a critique of all prior metaphysics. As Eckart Förster explains in his book The Twenty-Five Years of Philosophy, Kant realized that discursive thought becomes mired in contradictions whenever it applies itself to anything beyond the physical, sensible world. For Kant, this means that supersensible knowledge is simply impossible—the threshold could not be breached. But Kant’s denial need not be decisive for science, since, as Förster puts it, “One can just as easily conclude that, if supersensible reality is to be known, nondiscursive thought is required.” Though it first appears as a speculative idea, in this onto-epistemic logic of concrescence, we do not leave the empirical behind—we trace experience to its living source, and with Goethe, take the final result as the starting point for a new kind of natural philosophy and science.

The human “I” awakened to its own concrescent power becomes both the laboratory and the lantern for an organic empiricism or intuitive science. I’ll leave us with this quote from Steiner: “One discovers that, through this formation of the life of the imagination, one grows together with that which is the formative forces of the human body itself. After a time, one makes the discovery that the life of thought is, so to speak, nothing other than the diluted life-force of human growth. What forms us inwardly, plastically, in the physical body from birth to death is, in a diluted state, our imaginative life in ordinary consciousness.”

Let me just add that I realize this romantic account of evolution—cosmic evolution—could easily be critiqued as a kind of very narcissistic view of nature. I was particularly made aware of this by Gertrudis and Levi’s presentation and drawing on Lan yesterday, and I’m prepared for that criticism. I wish I could have fit more Charles Sanders Peirce into this presentation—it is in the longer paper I’m working on. Peirce, of course, was very influenced by Schelling. He writes in a letter to William James that no one was more influential than Schelling, and that he especially appreciated Schelling’s way of continually beginning again with a new system, which Peirce thought was especially scientific—which is ironic in light of Hegel’s criticism of Schelling as conducting his education in public for this very reason. What Hegel took as a criticism, Peirce sees as a form of praise.

Peirce’s semiotics is triadic and, unlike the structuralist semiotics derived from Saussure, which is dyadic, puts us into relationship with the real world. We’re not trapped and enclosed within our human form of language; all of nature is semiotic for Peirce. I think if we follow Peirce and his very rigorous semiotic logic, we can see how this kind of romantic account is not necessarily a narcissistic delusion—but I’ll leave it to you to decide. Thank you.

Q&A

Audience Member:

Thank you so much. I want to go back to the quote that you began with from Novalis at the very beginning. Sorry to make you go all the way back.

Matt:

No, it’s fine.

Audience Member:

But you only put half the quote: “The world must be romanticized. In this way, its original meaning will be rediscovered. Romanticization is nothing but a potentiation of potential”—so this potentiation. But he also said it’s also a depotentiation. It’s this oscillation between potentiation and depotentiation that I would suggest, especially in the Romantics, they were quite interested in. So you can see that—just to take an example—he goes through the poetic, he goes through the empirical, he goes through the practical, farming, the scientific, and he doesn’t really settle on any one. There is no sort of conclusion.

So, who is that goddess? It’s the goddess of nature, Diana—the wonderful, often-repeated figure of the time: the multibreasted goddess of Isis, goddess of nature, who has a figurative form. I think one of Novalis’s key arguments is that we are always in a figurative form—we are always in language. We can never get to the absolute. We almost have to recognize the limitation, as it were, on each of our articulations. Schlegel also talks about this: romanticism as an aspiration to this formative impulse, but then critique is also part of the recognition that we are only able to articulate fragments. But for Novalis, it’s kind of like constantly unveiling the goddess nature, and she’s always present there in some figurative form.

So I was wondering how that aspect of romanticism—not just potentiation but also depotentiation, that recognition of critique as part of the process of creation—fits into your account. I mean, it could tie to your last comment about Schelling, about him always coming up with new systems. They’re always just an expression, the absolute itself.

Matt:

Yeah, I mean, in the longer paper, I draw on your work, actually, to point out that in your study of these thinkers, you’re left without any evidence of anything like a unified system of romantic biology—and the fragmentary nature of this romantic approach is very important. In some sense, what I was trying to depict in that slide with the way that there’s always a hidden side to nature—the veiled goddess, right?—is the night. The light of the sun obscures the many stars in the night’s sky, right? And, you know, I like Schlegel—Friedrich Schlegel’s—point that it’s equally deadly for the spirit to have a system and not to have one, right? And so we have to always keep that tension in mind and recognize that the philosophy of nature is an infinite task. We will never complete it; we will never arrive at the final system.

Whitehead is known as a systematic metaphysician—he’s trying to do systematic metaphysics in the late 1920s, just when philosophy, both in its analytic and continental forms, is flying away from anything like system. But he’s approaching systematic philosophy as a radical empiricist, as a pragmatist. He wants his system to be open, and he demonstrates that in Process and Reality, where one of the categories he lays out in his “Category of Scheme” at the beginning—the category of “conceptual reversion”—on page 250 or thereabouts, he realizes, “Oh, I’m going to abolish that category because I’ve discovered another category subsumes it.” So he’s renovating his own metaphysics in the process of articulating it, and he just leaves it in there—he doesn’t go back and rewrite the book—which I think is an invitation to us to recognize the fragmentary nature, the partial perspectives that we have to work with when we attempt to understand the whole or the absolute.

Audience Member:

Thank you, thank you very much. I wanted to go back to—I’ve got a lot about the fragment, of course, but also the translation, because I just want to draw out something that I think is missing in that particular translation. Actually, if you translate it differently, it leads to more connections to what you’re actually talking about. So when Novalis talks about “qualitative realization of a potential,” he actually uses the word “potenzieren” and “potenzieren”—it could be “potentization,” but it’s actually using it in a sense of “exponentiation,” in a mathematical sense. He’s one of these few people who is poetic about mathematics, you know? So, he has “exponentiation,” so raising to a higher power—you have the identity, say, of a single number and you raise it to a higher power, so it’s like a self-increasing thing. And with “potenzieren” lowering, he uses also a mathematical term, which is not “lower organization”—that’s right. He inverts the operation, putting “cum.” And I think what’s really fascinating in Novalis is this image, or this mathematical metaphor. There’s one particular fragment which really ties in with what you were talking about at the end, and he says something like, “Human thinking is the quality”—so he gets this quality of potentization, not quantitative, it’s quality—“of self-intensification.” But then your thinking is the general forces of nature—and it might even use something like “plastic forces of nature”—raised to the nth degree, which goes very much in line with your idea that we have these kind of formative powers in nature, and human thinking is a flowering, a kind of flowering of what we find in the whole of nature. I mean, maybe you’re aware of all these things, but…

Matt:

Yeah, no, I appreciate that. I didn’t include the German in this one—I did in the other Novalis quotes—and I’m just using Robert Richards’ translation here, but I clearly need to revisit the translation, especially with that mathematical metaphor in mind. Thank you for bringing that out.

Audience Member:

And let me add another thing—something that interests me a lot about fragments. We tend to think of a fragment as just a piece broken off from a whole, but for Novalis it’s mainly because of the seed: the fragment contains the whole. What is the seed?—potential, right? The fragmentary nature is true, but each fragment is holographic in a sense; it contains the whole in miniature, in a somewhat diluted form, but still, it’s there.

Matt:

Yes, absolutely—good truth. Thank you.

Audience Member:

Thank you very much for your lecture. I don’t know whether I have to reassure you as to narcissism—the only thing is, I think the topic of narcissism is an interesting one for philosophers. For sure, without narcissism, we wouldn’t be here. So personally, I couldn’t consider it a negative at all. Meanwhile, I think there’s some things to be taken from more clinical approaches to narcissism—Freud, or Lacan on the mirror stage, for instance. They deal with questions of object investments, how one identifies oneself as something, and in that regard, the arrival of narcissism is quite confusing. But Lacan issues it in his first seminar, actually, on this technique. One of the things he clearly states is that, even at the level of identification in the image, in the “I,” it’s symbolic. You don’t arrive at it without another next to you saying, “Hey, you see that?” So it’s a weird operation, you know? Schelling has lots to say about this, and the question comes up for me: to take something as something is clearly the interest of the person. So I told you, I have PhDs working on the person—I wait and see.

Matt:

Yeah, I know—thank you. I hadn’t considered the connection between Lacan and Peirce, but I think Lacan was influenced by Peirce somewhat. Some people say yes, but what Peirce is saying represents something… and, as Lacan says, the signifier represents a subject for another signifier. So, he’s cutting the signifier’s autonomy apart, right? So, the “for something” is not present in the signifier itself. But at least in Peirce, the subject is sort of transitory, just like Whitehead’s account of concrescence—there are new subjects arising. We don’t have an enduring subjectivity through time; Whitehead has this term “society,” which is how multiple subjects inherit from one another in a very intimate way. So, our sense of personal identity is not one continuous subject for Whitehead, nor for Peirce. The interpretant, or the subject who is experiencing the sign’s relationship to the world in Peirce, is new in each moment. There’s an infinite process of semiosis, and what’s the interpretant in one moment becomes the sign in the next moment for a new interpretant. So, we’re not stuck in the same subjectivity—that’s Lacan’s “continued referral of one signifier to another,” and in between, the subject is, as Lacan says, “timed in the gap,” an effect of two signifiers.

What I appreciate about Peirce is that he’ll talk about semiosis going on throughout the natural world—there’s physiosemiotics, chemosemiotics, biosemiotics—so signification isn’t just something that human beings do in Peirce’s account. It’s a higher order or an intensification of something that’s pervasive in nature, and to me, that seems far more relevant to our ecological situation, to be able to break out of the human enclosure.

Audience Member:

Thank you very much. You’re probably the first person who talked about the idea of the “double stream of time,” which I was listening to. I’m talking about it, and I want to ask you about the idea—which is actually not mine, but it’s an old Aristotelian idea, and then Steiner reconfigured it—that the present is a continuously concrescent moment which integrates the past and also has a relation toward what the future is. But in the Aristotelian idea and in Steiner’s idea, there is something that endures, or is able to stop the stream of time, and which is not all the time newly created. And this is the spiritual, the idea, yes? How would you interpret that—that there’s something still remaining, enduring, not physical of course, but ideal?

Matt:

Yeah, I mean, Whitehead develops a whole theology—process theology. In a later section in this paper, I compare what he calls the “primordial nature of God” to the “I”—to this element that’s coming down, descending perpendicular to the stream of time. Whitehead has an account of the primordial nature of God as ordering the realm of possibility before the universe begins—in a logical sense, not temporally. I think that Whitehead also describes the way this primordial nature of God is an ingredient in, or an element in, the concrescence of all other actual entities, and it becomes conscious in the human being. This is at least resonant with Steiner’s understanding of the “I.” Whitehead also has the “consequent nature of God,” which is God in relationship to the world. So, the primordial nature is eternal and unchanging; the consequent nature of God grows with history, experiences the joy and suffering of every being. It’s one God, but it has these two aspects. I’ll have to share the rest of my paper with you to see if you can follow the comparison I make between Steiner and Whitehead on that question.

Audience Member:

Yeah, because there is something eternal in Whitehead. He’s a process philosopher, but he also has eternal objects, and he has this eternal divine being. So it’s more complicated than just “everything is process.”

Matt:

Exactly.

Audience Member:

We still have time for more questions. Else, I’d like to ask or to add—my turn! At some point, you spoke about how physical processes also manifest a kind of impulsiveness. And maybe not to get too into that, but how do we make sense of that? Because, of course, we can’t think of organisms as just popping out of nowhere—we have to understand their relation to other processes. But are these processes really normative in the same way as organisms? I would say that’s quite a difference.

Matt:

Yeah, well, on Whitehead’s account, we cannot sever the facts from values—every fact is a realization of some value. If we look at what are called physical laws, Whitehead’s understanding is that law is actually a product of an evolutionary process. It’s more like a habit. He’ll describe—as Dan mentioned yesterday—for Whitehead, physics is just the study of smaller organisms. An atom is a self-organizing system. Whitehead even describes the process by which the first hydrogen atom emerged, where you have a proton and electron forming a symbiotic relationship with one another, such that a new form of endurance is achieved, a new pattern of value is achieved. Once that pathway is discovered, the whole universe is transformed as a result. Similarly, when hydrogen atoms are drawn together into stars, and stars into galaxies, and so on—these are akin to organisms or self-organizing systems. These patterns of organization are not just determined in advance, like some preformation of laws imposed from eternity and constants that just happen to be perfectly aligned to allow for that type of order to emerge. Their achievements are expressions of value, right? So it’s a totally different rendering of the physical world. I think, as Dalia was hinting at, if we want to naturalize purposiveness and aim, we really have to go all the way down with this; otherwise, the organic becomes sort of closed in, the biological becomes closed in on itself, and we end up not being able to account for the transition from physics and chemistry to biology.

Audience Member:

Yes, you actually respond to a question I had, which is always presupposing in a way, in my understanding, that you somehow still start from physics and atoms, and then you try to build up the cosmos from there. I don’t know whether Whitehead did that, but just how you explained it now. Why not suppose it could be solved the other way around—that something alive was first? The principle of life, and that when that dies, the dead force becomes too strong, it dies and crystallizes, it becomes matter. Why do we start with matter first?

Matt:

Yeah, yeah. This is just a habit of thought. Why not conceive matter as a precipitation or a dead end product—something that was alive and then, having lost its creativity, becomes visible and becomes physical? Whitehead is a species of psychist. A lot of the analytic philosophers of mind who call themselves pansychists now are still thinking in a substance ontology; Whitehead’s is a different kind of psychism. But there’s no such thing as dead matter in Whitehead’s ontology—there’s no matter in Whitehead’s ontology. Creativity replaces this idea of matter as some kind of dead substance.

Audience Member:

That’s something I also can’t quite follow, because you can say there’s “creativity” inside the table, but the phenomenological appearance is different from something that is alive. That’s also a question I had about your talk: it sort of jumps beyond phenomenology, tries to find unifying principles, and for me this is not, of course, not completely un-phenomenological, but I can follow it easier if I think there’s a life process first—maybe mentality first, life, and then there is a precipitation of something that has been creative, but lost its creativity and becomes visible and becomes physical.

Matt:

Well, you know, Whitehead says in his book The Function of Reason—where he’s looking at evolutionary theory and he’s critical of Darwin’s account of natural selection as being able to explain complexification, and why life should give rise to forms of organisms that are comparatively deficient in survival power (we’re way more fragile than bacteria, which are functionally immortal)—so why is life evolving in this way if survival is the only point? But he says, you know, instead of trying to explain the more complex by reducing it to the simpler, why don’t we reverse that process and understand how it is that beings like us, conscious living beings, could come to exist in this world? What must atoms be like such that we could exist? That’s what he’s talking about—he’s seeking to develop an ontology from the perspective of life on this earth, and from the perspective of human beings alive on this earth. I know there’s, in terms of evolution being a process, where the human being didn’t exist and atoms and stars and galaxies and cells and all that led to the human being, versus seeing the human being as kind of there all along. I think Whitehead would allow us to view it either way, though in order to be conversant with the general understanding of evolution, he tended to talk about it as coming from a developmental process to the human.

Audience Member:

I would perhaps add one more thing from basic anthroposophy. Steiner distinguishes not really between matter and spirit or between principles, but between perception and thinking. This word “polarity” is the key for us at this moment in history. What we are about is a point, and matter is not substance, but what we perceive and call matter is, as Steiner says, matter in perception. If you grab it this way, then you get a completely new access to all these questions, because you can always ask: what is the perceptive part, what is the thinking or ideal part, and how are they brought together within our cognition? I completely agree with you and with Whitehead that the conscious human mind is the place where all these things become conscious, or where they appear—maybe not to say where they happen, but…

Matt:

Sure. And in Whitehead’s 1920 book The Concept of Nature, he begins similarly, talking about the split between concept and percept, and he thinks this has led to our inability to understand their synthesis or their unity, which has led to a picture where we have what he calls the “subjective dream” on the one hand, and then the “conjecture of physics”—so that nature poets should be congratulating themselves, he says, about the beauty of nature, because according to physics and the conjectured models, nature is soundless, scentless, colorless, right? So, he wants to heal the bifurcation by showing how concept and percept can be brought together again. I think there might be a parallel there.

What do you think?