We just wrapped the “Forever Jung” conference co-hosted by CIIS and the San Francisco Jung Institute. Tim couldn’t be with us in person, but I enjoyed his Zoom presentation on Jung and Simondon (video of his talk should be online soon; you can listen to mine here).

Below are some LLM assisted notes on Tim’s exegesis of the Simondon and Jung nexus, followed by some scattered thoughts of my own that draw together some of my comments in the dialogue with Tim.

Notes on Jung and Simondon:

Simondon was directly influenced by Jung, explicitly referencing Jung’s work on alchemy in relation to his own theory of individuation. In a 1960 presentation titled “Form, Information, and Potentials,” Simondon credited Jung with discovering in alchemical processes “the expression of the operation of individuation and of all the forms of sacrifice which suppose the return to a state comparable to that of birth.” Simondon saw his own project as generalizing Jung’s schema through “the notion of information” and “the study of the metastability of conditions.”

Both thinkers reject static conceptions of being in favor of becoming and process. They share an interest in how differentiated structures emerge from undifferentiated states, and how these individuated entities maintain ongoing connections to their sources. This common ground reflects their challenge to traditional Western philosophy’s emphasis on fixed substances and forms.

At the core of both thinkers’ work is a concept of an undifferentiated state that precedes and enables individuation: Jung’s “pleroma” and Simondon’s “pre-individual.” Jung describes the pleroma as “nothingness” that is also “fullness,” where “both thinking and being cease, since the eternal and endless possess no qualities.” Similarly, Simondon characterizes the pre-individual as “anterior to any appearance of phases,” harboring potentials energetically yet without predetermined forms or structures.

Both concepts function as necessary limit-concepts that enable thought while remaining beyond full conceptualization. Neither can be fully known through propositional knowledge but must be approached through experience. As Simondon writes, “we cannot know individuation in the ordinary sense of the term; we can only individuate, be individuated and individuate within ourselves.”

Both thinkers emphasize that individuation is not a once-and-done event but an ongoing process that maintains a relationship with the undifferentiated source. This relationship involves complementary movements of differentiation (becoming more distinct) and de-differentiation (reconnecting with the undifferentiated source).

Jung describes this dramatically in the Red Book, comparing de-differentiation to entering a volcano: “He who enters the crater also becomes chaotic matter. He melts… I myself become smelted anew in the connection with the primordial beginning.” Simondon similarly emphasizes that vital and psychic individuals maintain an ongoing “charge” of the pre-individual, unlike physical individuals that “jump the gun” and become fixed.

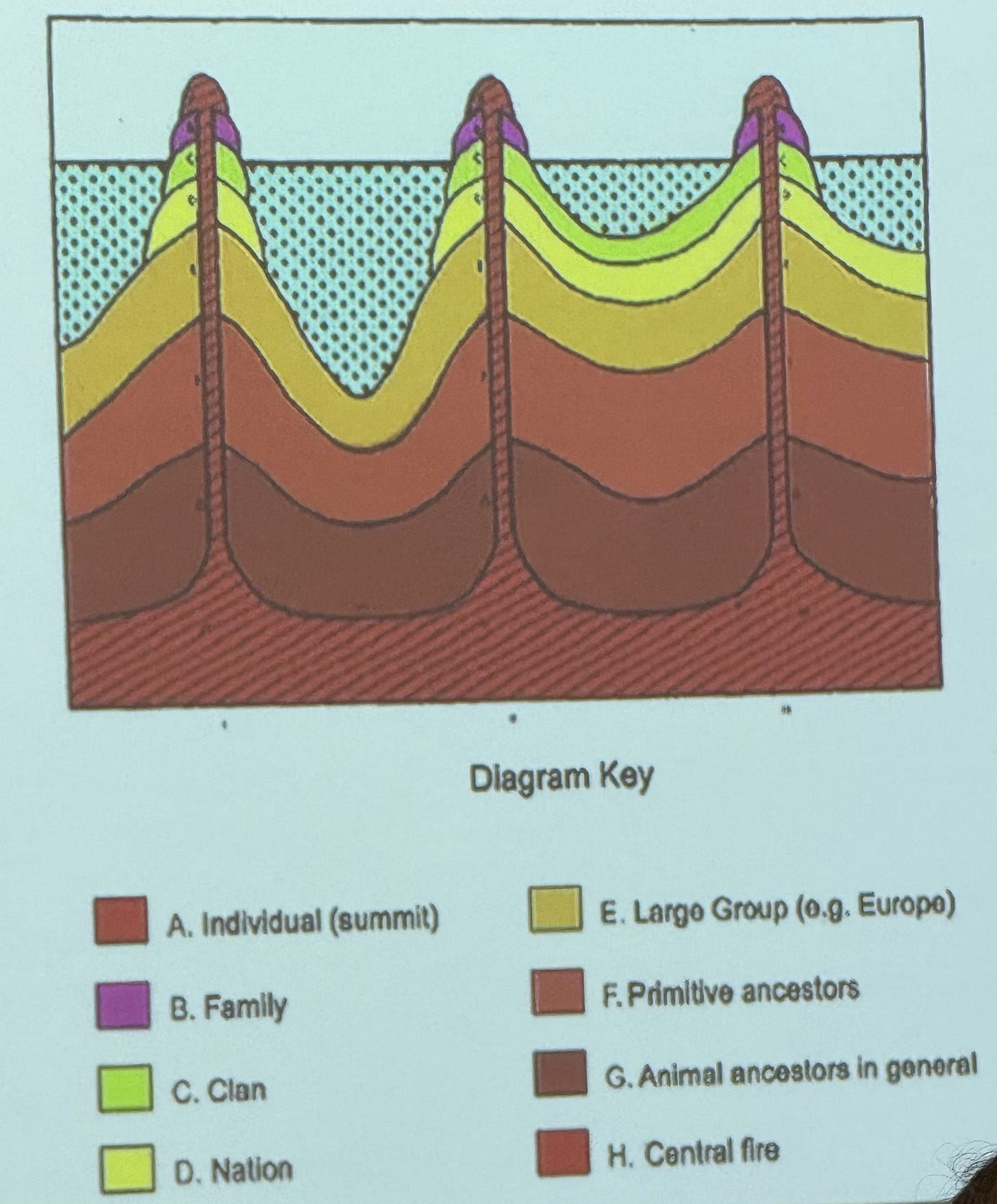

This concept connects to neoteny—the maintenance of juvenile characteristics into adulthood—which the participants interpret philosophically as maintaining an openness to the pre-individual source throughout development. Jung’s diagram of a “central fire” connected to the individual psyche through layers of collective structures illustrates this ongoing connection (see below).

Tim explored Simondon’s theory of images as quasi-organisms with their own autonomy or “luminosity.” For Simondon, images resist the subject’s free will and present themselves “according to their own forces, living in our consciousness like an intruder disturbing the order of a household.” This view resonates strongly with Jung’s concept of autonomous complexes and archetypes.

Simondon describes a three-stage “image cycle” that explains the genesis of psychic reality:

- Spontaneity: Images emerge from embodied motor tendencies and spontaneous movement

- Receptivity: Images become modes of receiving information, organizing into sensory-motor schemas

- Systematization: Images gain affective-emotional linkages, becoming capable of abstraction and recombination

This cycle shows how images develop from bodily origins into autonomous systems that constitute a “mental world” with its own constraints and dynamics—a natural theory of abstraction that connects to Jung’s understanding of psychic reality.

Some reflections of my own:

The parallels between Jung and Simondon aren’t accidental; there’s a real line of influence. Simondon’s very choice of the term “individuation” likely owes something to Jung. At minimum they are circling the same problem from different angles. What matters, though, are the structural connections: both think individuation as an ongoing process grounded in a pre-individual field (akin to Jung’s pleroma) that is never entirely exhausted by any formed individual.

…

Simondon distinguishes phases or domains of individuation:the physical, the vital, the psychic, and the transindividual (or collective). It’s tempting to treat physical individuation as a “once-and-done” affair: a crystal forms, and there you have it. But that picture is too tidy. Even the crystal, in practice and in principle, remains open to energetic, structural, and relational potentials that are latent in its milieu. Alchemy is a useful counterexample to the “finished crystal” myth: it keeps reminding us that materiality can be potentiated such that the vital and the psychic spill out of it without any need for an ontological gap. Ontogenesis (=individuation as a non-axiomatizable, ongoing genesis) runs through all the domains. The pre-individual is not a stage that gets left behind but a depth that remains available.

This is where neoteny becomes philosophically illuminating. Biologically, humans maintain juvenile plasticity far longer than other primates. That extended openness supports learning, culture, and symbolic transformation. Vital, psychi, and collective individuation depend on a kind of ontological neoteny: a maintained conduit to the pre-individual reservoir of potentials. Jung’s (or a Jungian’s) diagram of the psyche as a cone threaded by a lava tube that reaches down to a “central fire” captures this beautifully.

The individual sits atop various accreted layers—family, clan, nation, civilization, ancestral animality—but the tube remains open to the source. The pre-individual (Jung’s pleroma) continues to feed individuation; sedimentation never seals the passage.

…

Bringing this into conversation with contemporary physics helps clarify the stakes. Simondon’s pre-individual field resonates with possibilist approaches in quantum physics (eg, Epperson and Kastner’s res potentiae, and Stuart Kauffman’s insistence on “unprestatable” futures). In Laplacian determinism, unpredictability is merely epistemic. On the possibilist view, the openness is ontological: the space of future possibilities is not derivable even in principle—not by us, and not by any hypothetical divine intellect. That claim is relevant not only in biology but also in physics, where the same ontogenetic depth that Simondon and Jung articulate at vital and psychic phases is already at work. Possibility, properly ontologized, is like the lava that has not yet hardened into rock.

Our psyches typically repressed the originary surges for good reason. Open the lava tube too widely and you don’t get sages, you get messiah complexes and psychosis. Individuation requires modulating our commerce with the depths, not submerging ourselves in them.

…

I don’t want to collapse Simondon into Plotinus, but there’s a family resemblance worth mapping. Plotinus’s One is “beyond being,” not a member of the class of ones, not a countable unity. It overflows; it is fecund. Simondon and Deleuze rearticulate this pre-categorical source as metastable, pre-individual difference—less a supreme principle than a field of tensions and potentials out of which individuations precipitate. The point of contact is not doctrinal but functional: both accounts deny that formed being is self-explanatory and both require a more primordial, generative depth.

Seen genealogically, Western philosophy keeps wrestling with a paradox inherited from Parmenides: “Being is.” Zeno then breaks motion on the wheel of abstraction. Experience of the arrow hitting its target contradicts the geometrical deduction that it never can (it can only halve the distance infinitely), leaving a split between lived becoming and intellectual necessity. One recurring fix has been to postulate a mediating Logos. But we should handle the term carefully. Logos is polysemic and, in the oldest Heraclitean sense, names the very possibility of signification—the mediating, coordinating work that makes sense-making possible at all. In that mercurial register, Logos looks a lot like Simondon’s account of thought: not a prior blueprint but the operational relay across domains via analogical operations. Read this way, Logos is not a static principle pre-forming all outcomes but the active mediation through which new cosmoi emerge. This reading also underwrites Jung’s revisionary Christology in Answer to Job and Aion: Logossignifies the demand that even the divine undergo transformation in history—divinity and world, creator and creature, must co-individuate.

…

This all dovetails nicely with Whitehead. Creativity is ultimate; it is what allows each concrescence to be self-creating by recapitulating the original surge of becoming. God, in Whitehead’s speculative scheme, is not the metaphysical ground but an “accident of Creativity”—the most generic accident, whose primordial valuation of possibilities is then inherited by all subsequent actualities. Read in a Simondonian way, the primordial nature of God functions like a limiting ideal that structures a field of potentials without deductively fixing outcomes. The consequent nature (ie, God’s historical-relational pole) prevents any slide back into static perfection. Eternity here is not fixity; it is inexhaustible life.

All of this lets us recast a persistent theological temptation: the confusion of completeness with perfection. Jung is explicit that the drive to cosmic perfection produces shadow—an Antichristic backlash that wrecks the entire project of cosmogenesis. Historically, Augustinian predestination installs a theological determinism that gets secularized as Laplacian physics.

…

Jung, Simondon, and Whitehead both affirm continuity across domains: psyche is not a different substance from physics or biology. It is an operational difference, a distinctive regime by which occasions inherit, transform, and reintegrate potentials. There is no ontological gap.

So: Simondon’s pre-individual, Jung’s pleroma, Plotinus’s overflowing One, Whitehead’s Creativity, Schelling’s ground/existence polarity, Spinoza’s infinite substance (understood dynamically), and the quantum possibilists’ res potentiae all converge, not on a single doctrine, but on a shared refusal of onto-epistemic closure. Individuation is the ongoing mediation of the intensive depth of the preindividual tension with once-occurrent processes of formation, of possibility and actualization, part and whole. Any adequate account of evolutionary ontogenesis must allow the lava to flow, honoring the central fire without being consumed by it.

What do you think?